Article Contents

The Hybridity of Pattachitra Katha Media: The Folk-pop Art Narrative Tradition of Bengal

⬇ Downloads: 45

Cite

Majumder, S., & Banerjee, S. (2025). The hybridity of Pattachitra Katha media: The folk-pop art narrative tradition of Bengal. Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.65080/bk36he54

Majumder, Sreemoyee., and Banerjee, Supriya. 2025. “The Hybridity of Pattachitra Katha Media: The Folk-Pop Art Narrative Tradition of Bengal.” Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences 1 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.65080/bk36he54

Majumder, S. and Banerjee, S., 2025. The hybridity of Pattachitra Katha media: The folk-pop art narrative tradition of Bengal. Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), pp.1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.65080/bk36he54

Majumder S, Banerjee S. The hybridity of Pattachitra Katha media: The folk-pop art narrative tradition of Bengal. Adv J Bus Manag Soci Sci. 2025 Feb 7;1(1):1–11. doi:10.65080/bk36he54

1Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International University, Pune, India;

2Department of International Foundation Studies, Amity University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Received: 14 October, 2024

Accepted: 24 January, 2025

Revised: 21 January, 2025

Published: 07 February, 2025

Abstract:

Purpose: This study explored the post-colonial hybridity regarding Pattachitra art in Bengal, while analysing its change from an entirely religious storytelling medium to the dynamic visual form that pays heed to the modern socio-political problems.

Methodology: The research was conducted utilising a theme-based visual content analysis approach. The research examined six Pattachitra paintings spanning from traditional mythological narrative to the modern socio-political depictions. The artworks were selected using a purposive sampling approach.

Findings: The research found three main aspects evolving from the themes concerning the colonial era, the post-colonial era, the discussion on hybridity, evolving techniques and fusion of Pattachitra with Western art. Those include gender representation, national identity and global crisis response. From a gender perspective, artists had reconfigured the female figures using bold contours, expressive colour, and emotive postures, which challenged the traditional stereotypes and represented the feminist reinterpretations. The strand of national identity discovered how iconic mythological figures such as Durga and Krishna were reframed in the contemporary political contexts, reinforcing the cultural heritage in a modern period. In discussing the global crisis, artists engaged with events like 9/11 and the COVID‑19 pandemic, including symbolic motifs like masks, virus-based patterns, and frontline scenes in complex, scroll-style compositions.

Originality/Value: This study contributes to understanding the hybridity of Pattachitra as it bridges traditional art forms and modern global issues. It highlights how Pattachitra has adapted and remains relevant in post-colonial India, providing a tool for social commentary while preserving its cultural roots.

Keywords: Hybridity, pattachitra katha, folk-pop art, narrative tradition, COVID-19 outbreak, socio-political changes.

1. Introduction

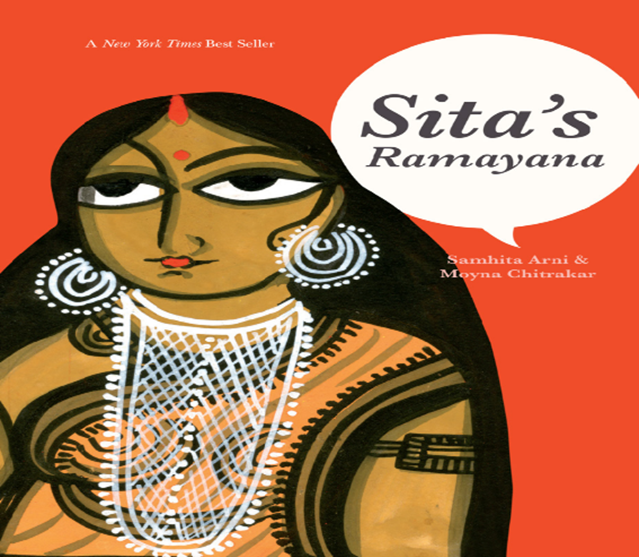

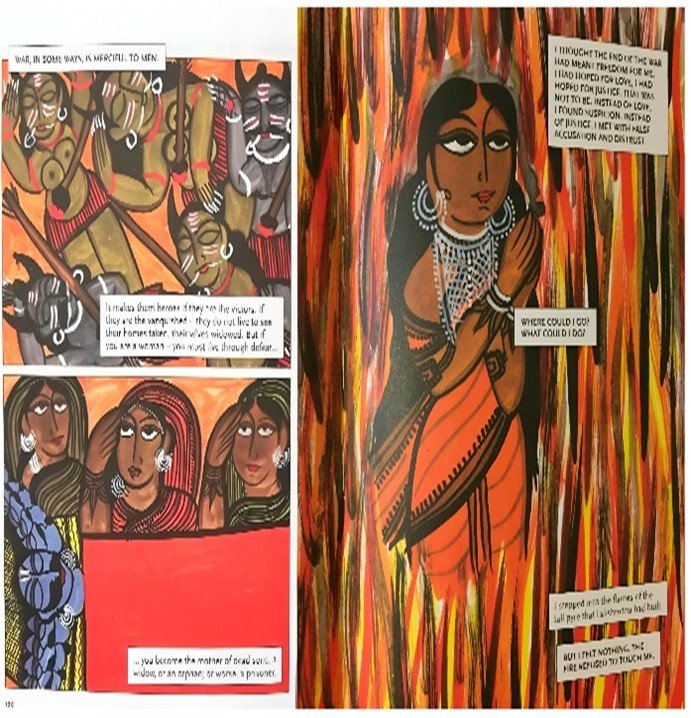

The traditional painting style known as Pattachitra art or Pattachitra painting originates from the Indian state of Odisha. The art form of Pattachitra follows its etymological basis, which means paint or pictures made on surfaces of paper, cloth, and palm leaves. Traditional artists practice Pattachitra art for multiple hours on paper surfaces to depict songs, stories, and folktales from Odisha relating to a 3000-year artistic tradition (Sethi, 2023). For example, Samhita Arni portrays women through Sita's Ramayana as objects whose battles involve major kingdoms and the' masculinity of the ruling men at stake. Fig. (1) is a depiction of it in which the face of Sita is framed amid foliage and fire, highlighting not just her inner journey (Sinha & Ali, 2024). It even shows how she stands at the crossroads of the mighty male conflicts. Thus, his suffering, including dignity, becomes a symbol of kingdoms and the honour of warrior men.

The Pattachitra paintings of Moyna Chitrakar illustrate an intensely emotional journey of Sita (never-ending exploration of freedom) narrated through Samhita Arni's graphic sequence (Dey, 2023). Traditional Pattachitra artists restrict themselves to red, green, yellow, black, white, and indigo colours (Sethi, 2023). Figs. (2 and 3) show her depiction of her emotional journey and use of patterned backgrounds.

The artists working on Pattachitra paintings derive white tones from conch shells, charcoal for black, and indigo for blue, while red comes from turmeric (Deb, 2022). Artists use these specific colours in artistic blending to produce remarkable results on their canvases for mythological storytelling. The painter uses specific stories of the place to create images that match their chosen theme (Sethi, 2023)

Fig. (1). Sita’s male conflicting depiction (Sinha & Ali, 2024).

Fig. (2). Sita's close-up with striking and expressive eyes shows her emotional journey, which is captured by simplicity (Kalplata, 2025).

Fig. (3). A narrative panel depicts a moment from Sita's exile, including lush foliage, patterned backgrounds, and symbolic gestures in rich, earthy tones (Sethi, 2023).

In the realm of traditional art forms, Chitrakathi (oral storytelling and performance art from the western part of Maharashtra), together with Pattachitra (traditional cloth-based scroll paintings established in districts of West Bengal and Odisha), kalamkari (scroll narrative art developed in Andhra Pradesh) and Cheriyal (long narrative scroll paintings originating from Telengana) are the cornerstone of art in India evolving with time (Basu, 2023a). The transformation highlights the complexities of cultural identity since artists navigate between local traditions and global narratives. The hybridity of the Pattachitra is not merely adaptation but a profound reimagining, challenging the notion of fixed cultural boundaries.

The Pattachitra art/painting also reflects tribunal culture and attributes for painting and storytelling, such as the Patua people from Bengal. Patua artists enact the performances as they unfurl the painting scroll of Pattachitra by singing the painted tales (Rohila, 2023). For example, the drawings of Sita's Ramayana were created by Moyna Chitrakar, a Bengali Patua artist. Moyna portrays Sita, a Hindu Goddess, as a dark-skinned character. Sita (a Hindu Mythological Goddess) is presented in most works as fair-skinned. However, in the woman-based Ramayana, Sita carries dark skin, which is more appealing and closer in reality to Indian women. It represents Pattachitra's ideation of a more natural communication of emotions, reality, and life experiences. This technique of art/painting helped to combine, include, and portray nature, culture, and society coexisting from the lucid dialogue.

As times changed, Pattachitra Katha, a genre of mass media and cultural communication, adopted global transformations with expanding knowledge systems, global outreach, and technical support (Rohila, 2023). Automatically, the transformation came into the intangible sector of its small tradition as folk media. The example here can be taken from Patua 's use of Pattachitra art, which worked on highlighting their issue and living experiences through this art form. The Patua converts personal encounters into painting visuals as well as music compositions. The long-established vernacular history of rural communal habitats and their natural surroundings is documented in various manuscripts, print formats, and oral and musical performances. Based on these aspects, Pattachitra continues interrelated traditions that have utilised musical elements in their past practices (Basu, 2022). Based on the above explanation, the study's research question is, how does Sita's Ramayana adaptation by Pattachitra art challenge the traditional gender representations referring to Indian mythology? This question aims to guide an in-depth exploration of the relationship between traditional art forms and modern reinterpretations, paying heed to gender dynamics within the mythological narratives. It even sets the stage for analysing how contemporary adaptations, such as Arni's Sita Ramayana, use traditional media to convey cultural perspectives.

2. RESEARCH PROBLEM

The Pattachitra art has been a well-discussed subject in several studies, whereas a thorough understanding of the hybridity confined to the post-colonial era has not been explored in depth. Works of art covering its historical, religious, and cultural characteristics have prospered in the existing literature. However, studies delving into how Pattachitra art has evolved over the years, adopting and merging the features of Indian and Western artistic psychology, are lacking in the literature research. However, (Zanatta & Roy, 2021) only considered the adaptation of Pattachitra to the COVID-19 pandemic, and their discussion did not focus on its hybridised artistic form but on the social context. Correspondingly, (Katiyar, 2019) investigated the ornamentation and narrative tradition of Pattachitra without writing about the influence of colonialism and post-colonial modernity on its visual language. (Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024) attempted to examine the identical Patua in colonial and post-colonial Bengal; however, these works did not study the hybridity of the local tradition and Western artistic innovation. Similarly, (Chowdhury, 2022) and (Mondal, 2022) worked on the religious and musical aspects of Pattachitra. However, they ignored the transformative aspect of the hybridisation of the medium regarding the elements of narrative and visual structure. To address this gap, this research analyses how Pattachitra's visual language and thematic content evolved via hybridity in the post-colonial period and their adaptation to the contemporary socio-political contexts.

Apart from this, the study also aims to fill a crucial gap while integrating the gender dimension into the analysis regarding hybridity in the post-colonial Pattachitra art. As preceding research like (Chowdhury, 2022; Katiyar, 2019; Mondal, 2022; Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024), and (Zanatta & Roy, 2021), has illuminated the ornamentation, musical traditions, religious themes, and socio-political narratives, they do not have examined critically how the hybridity transforms the gendered representations in the visual language. Based on the post-colonial feminist insights which forefront the “double colonisation” regarding women by imperial and patriarchal forces (McMullen, 2021), the research interrogates how the Western techniques, along with the indigenous narrative forms, tend to reshape the portrayals of femininity, including masculinity in Pattachitra.

Moreover, the research discovers if hybrid images like the layered compositions, Western-style views, and new colour palettes tend to alter the traditional gender norms embedded in the mythological iconography (Majumder & Banerjee, 2024). For example, the depictions of Sita in Samhita Arni’s Pattachitra adaptation might subvert or even reinforce patriarchal ideals, which reflect extensive cultural negotiations in post-colonial India (Anjana & Savitha, 2023). While focusing on how the hybrid visual strategies affect the gender representation, the study links the artistic form evolution with the shift of gender politics, providing a more nuanced level of understanding related to the cultural hybridity, paying heed to both the aesthetic innovation and its implications regarding gender identities.

The paper explores the evolution of Pattachitra Katha, focusing on its role as a medium of cultural communication and a vehicle for social change. The research has insights into how this art form resonates within contemporary discourse, evaluating the interplay of tradition and modernity. It highlights its significance as a historical artefact and a living practice engaging with today's globalised world. A considerable theoretical framework to analyse the emergence of Pattachitra Katha in colonialism and identity politics can be post-colonial theory (Nasrullah, 2016), combined with cultural studies. The framework explains how colonial histories influence people and how communities outperformed the socio-political and economic dominance in negotiating their space (Rukundwa & Van Aarde, 2007). Overall, the article has contributed to discovering Pattachitra Katha hybridisation while blending traditional folk art with modern media. It has also examined the role of cultural resistance in identity politics. However, a gap exists in analysing the detailed effects of modern techniques and platforms on emergence and how international trends even shape such folk-pop narrative tradition.

3. Methodology

Visual content analysis was used in this research to investigate the hybridity in the post-colonial era Pattachitra art, which evolved out of the folk-pop art narrative tradition of Bengal. Visual content analysis in this research followed a structured and rigorous approach for uncovering the hybridity in the post-colonial Pattachitra art, which is also explained in the studies of (Musa, 2021) and (Spencer, 2022). Starting with a purposive sample of six paintings, ranging from traditional mythological scenes to modern socio-political narratives, the researcher employed qualitative visual methods rooted in the interpretive techniques of Krippendorff. Moreover, a detailed coding framework was made for identifying the markers of hybridity, which include shifts in the composition, introducing perspective whereas layering from the Western traditions, transformations in the colour palette, i.e., the natural pigments blended with the imported dyes as well as the development of novel symbolism which reflects the global events. All the artworks were examined manually using this codebook, which ensures systematic documentation regarding the visual factors across domains such as iconography, form, colour, and thematic content. Moreover, the analysis went beyond the objective descriptions, focusing on the latent meanings and patterns regarding how the traditional linear storytelling, overstated facial features, and religious motifs amalgamate with the signs regarding Western impact and contemporary subject matter.

Furthermore, comparative assessment among the early and later works showed clear visual transitions, i.e., the initial images adhered to the flattened opinion and mythic themes. In contrast, later paintings included the spatial depth, secular motifs, and layered compositions indicative of Western stylistic integration. By this interpretive lens guided by abductive reasoning, the research tends to position the artworks in a "third space" in which Indigenous and Western visual languages merge. Eventually, the method shows how Pattachitra art evolved from an entirely religious medium to a dynamic and socially engaged form capable of commenting on global issues and reshaping the cultural identity of post-colonial India.

This paper explored how Pattachitra artists adapted indigenous artistic techniques to assimilate Western influence. The researcher has selected six images to highlight the pattern, structure, and thematic shifts in Pattachitra during this time, such as (Chowdhury, 2022; Katiyar, 2019; Mondal, 2022; Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024) and (Zanatta & Roy, 2021), who work on various subjects ranging from feminist iconography to the 9/11 attacks and the pandemic of COVID-19. The wide range of themes presented in Pattachitra covered a broad spectrum of local and global concerns within the folk-art tradition. It provided a universal understanding of how Pattachitra progressed.

In analysing these arts, the construct has been developed around the key visual elements that reinforce the hybridity within, some of the composition changes, the use of a new colour palette, the placing of symbolism, and the inclusion of new socio-political themes. Moreover, in particular, they blended traditional elements of Pattachitra, such as exaggerated facial features, linear storytelling with religious iconography and modern techniques and themes. The artists adapted depth, layering, and use of contemporary subject matter such as gender, national identity, and global crises. This process allowed Pattachitra to be analysed as a form that, through research, has emerged from being a medium of purely religious storytelling, into one that can comment on issues of relevance at a global level, depicting the ever-evolving interaction between tradition and modernity. The research focused on these selected images to explore how Pattachitra remained a medium of dynamic hybridisation of Indigenous and foreign influences to express culture and make social comments.

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Colonial Influence on Art in Bengal: Subjugation, Westernisation, and Hybridisation and its Influence Over Pattachitra

The British colonial rule in India, particularly from the 18th to the mid-20th century, influenced the art culture of Bengal. The British colonial administration sought to impose European art forms, structures, and ideologies that often-subjugated indigenous practices and redefined artistic norms (Rahman et al., 2018). They argue that British colonialism brought with it a deliberate effort to control cultural production, using art as a tool to reinforce colonial ideologies. Colonial artists often depicted Bengal through a European lens, emphasising themes of subjugation and exoticism, which presented a distorted view of the region's culture and people. Western art institutions, such as the Calcutta School of Art, were established to teach European techniques to Bengali artists, creating a space for developing new artistic styles that adhered to Western ideals of art (Basu, 2023a). As (Kaviraj, 2003) explains, the colonial period in Bengal marked the beginning of a duality in the region's artistic culture where colonial influences coexisted with indigenous practices. The impact of Western modernism and colonialism on Bengal’s art led to the emergence of a new, complex artistic identity that combined elements of both worlds (Mitter, 2008).

Drawing on the concept pf Homi Bhabha of mimicry and hybridity in which the colonised subject i.e., ‘’becomes a partial presence” by the imitation which is “almost the same, but not quite” (Bhabha, 2021), the researcher reassessed Pattachitra’s colonial-era fusion. British-led art education had not just superimposed techniques i.e., the local artists engaged in the “strategic reversal” of dominance by the mimicry, entrenching subversion in their adaptations. It suggests that colonial impacts on Pattachitra had an inherent double-edged ambivalence, concurrently consolidating and destabilising the imperial authority (Iqbal & Rehan, 2020).

Furthermore, by internalising the European perspective with realism, Pattachitra artists entered Bhabha's "third space, " a liminal zone of the cultural negotiation (Saha, 2021). Such a hybrid terrain created the cultural ambivalence, which is a mix of compliance and critique, most of it like the colonial-era Indian painters whose artwork resembled European art, however, had been defiantly Indian. The result was not stylistic dilution; instead, it was a negotiated identity that weaved together folk tradition with colonial modernity. Such a layer demands that people treat colonial-era Pattachitra not as passive recipients but as active participants in the post-colonial discourse. Their mimicry of European art had been an act of symbolic resistance, which exposed the inconsistencies of colonial ideology and sowed the seeds for highly overt hybridity in the post-colonial era.

4.2. Post-colonial Bengal: The Reclamation of Cultural Identity through Pattachitra Art

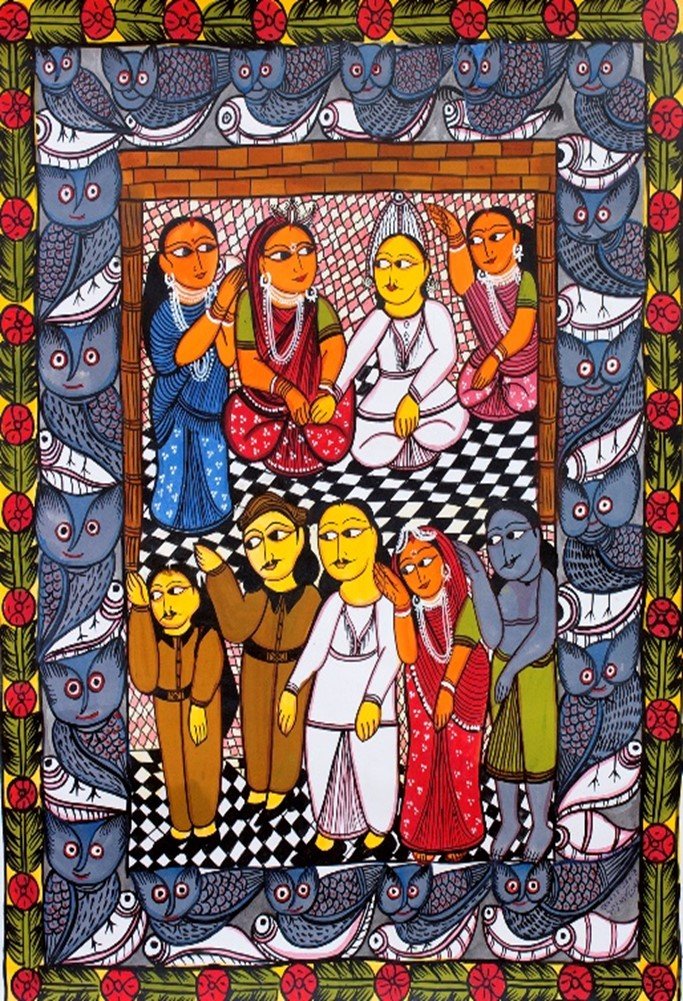

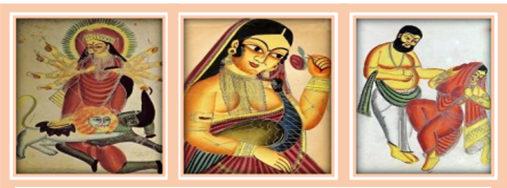

Following India's independence in 1947, Bengal experienced a cultural and artistic revival as artists sought to reclaim and reconstruct their identity after colonialism. (Basak, 2011) discusses how post-colonial Bengal witnessed a reassessment of regional history and the emergence of new forms of cultural expression that celebrated Bengal's heritage. Post-independence artists sought to reconnect with their pre-colonial roots, drawing inspiration from local traditions, folk art, and religious iconography. This period saw the continuation and transformation of pre-colonial art forms, such as the Durga idol, which became a religious symbol and a national emblem of empowerment and cultural pride. This is highlighted in Fig. (4) by (Katiyar, 2019), in which the first picture from the left represents a modern integration of the Durga idol over a lion, alongside different animal features, including a lion, elephant, and a sun. It represents a contrast and multi-layered meaning about the occupancy, power, influence and relationship of Durga Idol, but in a more modern aspect.

As (Deb, 2021) notes, the post-colonial period witnessed the reinvention of the Durga idol, reflecting the changing socio-political landscape. The representation of Durga evolved to reflect a more assertive and independent India, a powerful symbol of both religious and national identity. Similarly, Bengali artists began to focus on themes of independence, freedom, and cultural rejuvenation, seeking to capture the complexities of post-colonial life in their work (Baliga, 2016).

The post-colonial era saw the rise of commercial art in Bengal, with artists like (Datta, 2018) discussing the consumption ethos of Bengal's art market. The demand for art grew as artists responded to the needs of a rapidly modernising society, and the economic impact of partition and independence shaped the production and distribution of art. The interplay between tradition and modernity continued to define the artistic landscape as artists strived to express the duality of their cultural heritage and contemporary experiences.

Post 1947 Pattachitra had been more than a cultural revival as it had enacted the post-colonial strategy. Drawing over Bhabha’s “third space”, the artists did not simply revert to the pre-colonial forms (Awana, 2023). They had reworked them in a hybrid framework that blended folk motifs with the residual colonial aesthetics. It created a cultural ambivalence in which tradition and modernity coexisted in tension. Deb's analysis of the Durga icon not only discusses religious sentiment but also examines how it has been a feminist nationalist symbol that reclaims power through imagery. Hence, the post-colonial Pattachitra tends to engage in an active visual negotiation of identity, challenging the monolithic narratives and asserting self-defined cultural authority.

4.3. Contrasting Analysis of Hybridity in Post-colonial Pattachitra Art

Pattachitra, a deeply rooted folk art tradition of Bengal, has undergone significant transformations in the post-colonial era, shaped by colonial encounters, modernisation, and globalisation. While traditional Pattachitra was primarily used for religious storytelling, post-colonial Bengal saw it evolving into a hybrid art form that integrates new themes, visual styles, and socio-political narratives.

4.3.1. Hybridity in Visual Language: Traditional Forms with Modern Aesthetics

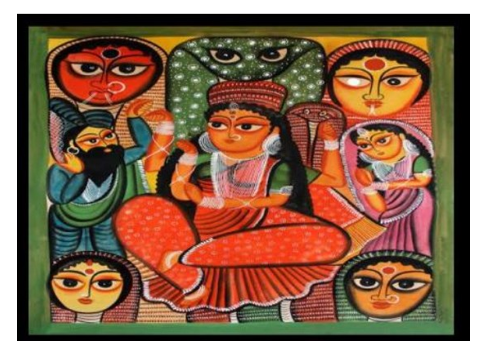

Pattachitra’s visual language has evolved over these images from pure religious and mythological storytelling to a more hybridised form capable of absorbing contemporary themes, social realities, sensibilities, and newly developed artistic expressions. Start with Fig. (6) by (Mondal, 2022) because of a dominant central female portrait that some could interpret as a goddess or some symbolic representation of power. In traditional Pattachitra gods, the compositions had to be balanced, there was strict frontality and standardised facial features to keep a divine and nearly detached presence. However, this rigidness is abandoned in this figure as the female has been painted more relaxed in her posture and the other characters around her with mixed emotions and gestures. Considering the features of humans in Pattachitra, it has a signature element of exaggerated, bold black outlines and large, expressive eyes, and the details of the attire and jewellery suggest that this has an adaptation of modern stylistic preferences. The red and orange hues of the clothing intensify the deep green colour of the background. This contrast is significant because red and green are associated with fertility and strength in Bengali art and culture, characteristics linked historically with female divinity. These overlapping pictures/portraits help to create an effect of layers, which was alien to pre-colonial Pattachitra, as its interest was going to be more on two dimensions, as well as linear storytelling.

The change apparent in this image is related to post-colonial artistic movements, as (Basak, 2011) discussed, which are a return to indigenous artistic forms with a dosage of new visual influences. Pattachitra, as a form of art in the post-colonial period, has seen artists strategically incorporating modern refinements without losing the folk essence (Rahman et al., 2018), unlike in the colonial period, where the Western artistic traditions such as realism and perspective were forcibly imposed on the Indian artists. The patterns and facial features here are traditional, but the expressions and compositional layering signify a more nuanced, individualised storytelling. This figure represents a goddess or a powerful female, which is related to religious symbolism. However, it could also be seen as an illustration of contemporary feminist narratives. (Deb, 2021) explains that post-independence art sometimes turned figures like Durga into the representation of a nation's strength and resilience.

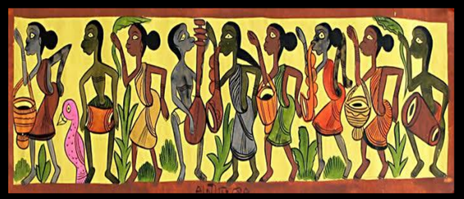

Fig. (5) by (Mondal, 2022) is a complete shift from sacred themes as it entered the themes of the real world without depicting sacred women, but showed Chouko's path on popular folklore of Manasamongalkavya. However, these are significant because even in conventional Pattachitra, the everyday scenes of nonreligious nature were not depicted in the scroll paintings and were found in the Kalighat paintings, appearing under colonial influence. Also, in the folk style, the elongated limbs, exaggerated face, and rhythmic arrangement of figures remain as evident from Fig. (4) by (Katiyar, 2019). However, there is a dynamic element through repetition and movement that was not as apparent in earlier Pattachitra. Pope employs muted earthy tones in this painting, including a muted palette of browns, yellows, and ochres, reaffirming a commitment to indigenous visual traditions. However, the women's body language and lively postures are adapted towards a more alive and human-centred storytelling style. In line with (Datta, 2018), who observes that post-colonial Bengal's art scene progressively engaged with contemporary issues, such as urbanisation, gender, and economics, art increasingly assimilated tradition and modernity.

Developing on Bhabha’s notion regarding “third space” in which hybrid identities evolve through the cultural negotiation, but not erasure, the images like Mondal’s central female figure tend to achieve more than aesthetic variation (Iqbal & Rehan, 2020). Moreover, they also enact feminist reclamation, which means bold outlines with the emotive colour change the goddess from the passive icon to the active subject. The combination of maternal as well as divine imagery develops the cognitive dissonance, which includes an inherently post-colonial tension between the inherited myth and the contemporary identity politics. Such visual hybridity has been a resistance as it weakens the patriarchal archetypes as well as signals the gendered subjectivity in Pattachitra’s emerging semiotic field.

4.3.2. Changing Narratives: From Mythological to Contemporary Social Commentary

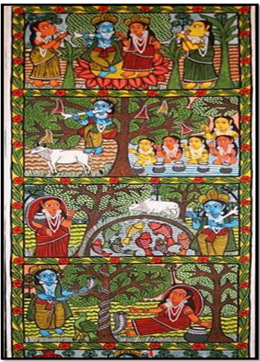

The Pattachitra made before the colonial age were essentially religious and didactic tools, narrating the divine stories with rigid composition and symbolic storytelling. According to (Kaviraj, 2003), Bengal, prior to the British invasion, featured a dual artistic tradition wherein indigenous and more elite courtly art lived together simultaneously, but all such art focused essentially on mythological storytelling. Despite this, in the post-colonial era, folk art forms like Pattachitra started depicting socio-political themes as the spirit of independent India, and the wish to associate themselves with contemporary global happenings arose. Fig. (7) by (Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024) covers the 9/11 attacks, and Fig. (9) by (Zanatta & Roy, 2021) portrays the COVID-19 pandemic situated well within this bracket as an expansion of thematic scope. Although Pattachitra draws its visual syntax and narrative structure from [original] Pattachitra, such as presented in Fig. (8) by (Chowdhury, 2022), it can be argued that these two figures prospect an idea about the evolution of Pattachitra art from a critical historical aspect to a political commentary.

Fig. (4). The common theme of bengal pattachitra. Source: (Katiyar, 2019; p62).

Fig. (5). Chouko pat on popular folklore of manasamongalkavya by Swarnachitrakar 2018. Source: (Mondal, 2022; p63).

Fig. (6). Tribal Pattachitra Bengal. Source: (Mondal, 2022: p65).

Fig. (7). Swarna Chitrakar’s Pattachitra on 9/11. Source: (Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024; p57).

The context represented in Fig. (8) of Krishna Leela highlights the divine life journey, activities, or roles of Krishna from being a God-child to a hero, portraying his naughty and playful side. This is in accordance with the initial role of the development of Pattachitra art to portray religious stories, incidents, religious rituals, and public performances (Mokashi, 2021). The art was considered a medium to promote the religious scenes of goddesses, gods and scenes related to Hindu mythology (Pratha Cultural School, 2025). Thus, considering the representation of Krishna Leela in Fig. (8) highlights that in the pre-colonial era, art was related to the context of religious prospects only afterwards with the possible influences of culture, time, warships and rulings the art modified in perspectives portrayed while maintaining its initial connection with the old Pattachitra scroll tradition.

Fig. (8). Krishna Leela Pattachitra. Source: (Chowdhury 2022; p69).

Pattachitra redefines that typical artistic effect of Pattachitra but with a little bit above the ordinary and deviates Pattachitra in a radical way. For instance, in contrast to classical examples that include warm, earthy tones produced by natural pigments, this piece utilises a monochromatic (grayscale) palette which intensifies the gravity associated with the subject matter of 9/11. In terms of composition, this Pattachitra is a huge deviation from the pre-colonial ones as the congested and overlapping nature of the composition had never been seen earlier; while the figures were arranged in distinct registers, or as in many cases, Pattachitra was composed of structured storytelling panels. The sense of claustrophobia and instability of the event is mirrored in the picture where the dense layering of buildings, aeroplanes and human figures are piled in upon one another.

One of the key elements of the concept of hybridity in this image is the central bearded figure towering over the scene in an omniscient and authoritative manner. In classical Pattachitra, the gods and the celestial beings used to be portrayed at the top of the composition, overseeing human affairs with the divine order, as highlighted in Fig. (5) by (Mondal, 2022). However, in this instance, the figure's demeanour, attire, and placement surrounding the context could be interpreted as an unidentified political figure, a provider of surveillance, or even an abstract figure/portrait representing power and control. The way post-colonial artists reuse the traditional visual motifs and give them new meanings, often political, is exemplified in this reinterpretation of divine positioning within a modern, global tragedy. Also, it shows how Pattachitra is no longer a tool of religious devotion but a medium of global socio-political critique through the fusion of folk aesthetics and contemporary anxieties as shown in Fig. (7).

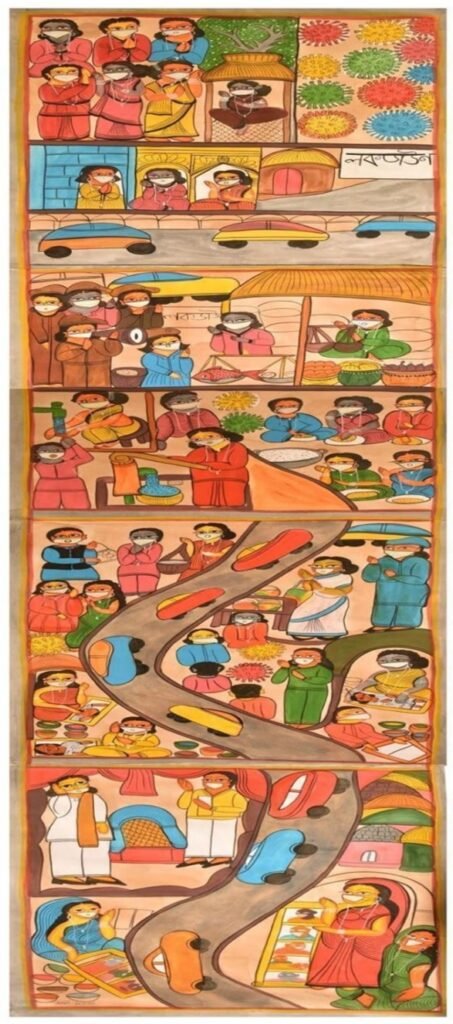

Despite the linear, panel-based storytelling model adopted in Pattachitra, the COVID-19 scroll painting deviates from the subject matter and iconography of the traditional Pattachitra painting. In Pre-colonial Pattachitra, God figures were the flag bearers; this painting portrays normal people facing modern health crises. With the representation of face masks, ambulances and hospital imagery in an invocation of a supposed modern context, Pattachitra's adaptability is exposed. Here, the colour choices are quite different from those in the 9/11 painting. Where the 9/11 image uses muted monochrome, the colour in the COVID-19 scroll remains the bright celebratory hues of folk art. An essential characteristic of folk visual traditions is the paradoxical use of colour, depicting a grim reality with vibrant tones and not an emotional picture, because in many cases in such traditions, the symbolic and decorative functions predominate over the literal emotional one.

Another aspect of hybridity can be seen in another pattern of the COVID-19 scroll. Here, the semiotic function assumes traditional floral and geometric motifs that were once used as ornamental fillers in religious Pattachitra. Scattered across the panels, decorative circular patterns resemble depictions of the virus on the microscopic level, as an artistic convention is transformed into an apt symbol for disease and contagion. This adaptation of Pattachitra patterns from ornamental to semantic reveals a modern perspective of visual semiotics.

Furthermore, the panel composition reflects the pre-colonial Pattachitra storytelling hierarchy; however, its subjects are purely contemporary. At the upper levels, representations include community rituals and public health responses; in the lower panels, we see individuals surviving with masks on, at work and the store and interacting. It characterises a post-colonial tendency towards the lived reality rather than the idealised cosmic narratives of the earlier Pattachitra.

As both 9/11 and COVID-19 artworks, the artworks here are testimony to the post-colonial transformation of Pattachitra from its sacred storytelling function to a tool for social engagement. As (Basak, 2011) also mentions, there was a rise in the reclamation of Indigenous art forms in post-independent Bengal, but in its revival, it was not about stagnation but evolution. Initially, British colonial rule distorted and controlled artistic production; however, the post-colonial artists revised folk tradition in their terms to face contemporary issues but in traditionally formed ways. This hybridity of Pattachitra allows it to culturally translate the global through an indigenous framework, it is the bridge from past to present, from local to global and from traditional to modern.

4.3.3. Colonial Legacy and Modern Globalization in Pattachitra

To point out the effect of British colonial rule on Bengal's artistic traditions, especially when Pattachitra artists started introducing Western art techniques and subjects into their art. According to (Rahman et al., 2018), British colonialism attempted to control and reform indigenous artistic production by introducing European realism, perspective, and portraiture to the local artistic landscape. The impact of this influence is most conspicuous in the earlier set of colonial-era images in Fig. (4) by (Katiyar, 2019), as the flat stylised figures of the traditional Pattachitra start taking up Western academic refinements.

Among the other portraits, one depicts a woman holding a flower, which comes from the rigid frontal portraits of pre-colonial Pattachitra. This image is not an entirely flat two-dimensional composition with no shading, anatomical rendering, or softer facial features, all indicating a European portrait tradition that this image engages with. At the same time, women were typically depicted symbolically and decoratively in classical Pattachitra as goddesses and allegorical figures, such as in Fig. (8) of Krishna and Leela by (Chowdhury, 2022). The shift to personal expression and naturalistic rendering in this Pattachitra art, as represented in Fig. (4) by (Katiyar, 2019), suggests an impact of British academic portraiture in which reality and psychological depth were stressed. It reflects, among broader shifts in Bengali art under colonial rule, that Western artistic institutions like the Calcutta School of Art prompted local artists to abandon religious storytelling in favour of European aesthetic values (Basu, 2023b).

Nevertheless, these Western techniques were introduced in India for the first time under colonial rule; in their post-colonial age, the artists had the option to apply them rhetorically to the present political and social problems. Such transformation of an art form is best represented in the 9/11 artwork like Fig. (7) (Mondal & Bhattacharjee, 2024), which utilises industrial and urban imagery as well as war images that are superimposed with images of natural landscapes and divine figures found in pre-colonial Pattachitra. In earlier works, the centre contained gods and mythological beings with a hierarchy of symbolic visuals and structured decorative elements around it. However, the 9/11 piece overturns this spatial order through crashing planes, towering skyscrapers, and displaced human beings; there is an impression of chaos and current instability. These depict the anxieties of globalisation, a tremendous departure from the cyclical, harmonious storytelling seen in traditional Pattachitra, but instead, concentrate on the berserk angular lines of some huge skyscraper or warplane.

Likewise, the COVID-19 scroll painting by (Zanatta & Roy, 2021) is an image of the post-globalisation world where global socio-political documentation happens through the former traditional folk-art means. Early Pattachitra was primarily deployed for ritualistic storytelling, but this contemporary version documents a public health crisis worldwide and features masked figures, urban hospitals, and street scenes of pandemic life. This distinction between pre- and post-colonial Pattachitra again sets the difference in subject matter from the spiritual to the contemporary in ambulances, urban marketplaces, and emergency medical settings as opposed to the villages, temples, and divine realms. Even though the subject matter is not bright, the colours used therein are well-lit and celebratory not because they are figuratively bright, but symbolically so, continuing a traditional folk-art method of using vibrancy rather than emotion, permitting the painting to join the styles of a traditional aesthetic with modern documentary storytelling.

The way colonial rules expanded the subject matter and artistic methodologies of Pattachitra illustrate how, at first, colonial influences were carried over, introducing novel scholarly conventions to the Pattachitra in West Bengal; but in the post-colonial era, the artists have taken the hybridity to the next level and use Pattachitra as a medium of expression in terms of international matters of socio-political nature such as the concept of Covid-19 scroll painting extracted from (Zanatta & Roy, 2021). In this transformation, (Basak, 2011) believes that art functions as an attempt to reclaim cultural identity, when post-independence artists endeavoured to revive the old pre-colonial artistic genres while also introducing modern themes congenial to the modern audience. As a hybrid, Pattachitra does not recognise any artificial or arbitrary division and remains a dynamism, an evolving art form always negotiating between the indigenous and foreign, tradition and modernity between the local and global, but always modifying in the process of being and 'becoming under the influence of culture change in West Bengal.

As earlier Pattachitra had served the pastoral and devotional needs, the COVID-19 scroll uses the folk visual syntax for processing the collective trauma. Ritual motifs even morph into the viral forms that is floral patterns had been symbolic of contagion which turned ornament into the semiotic archive (Zanatta and Roy, 2021). Such repurposing situates the Pattachitra to be a communal coping mechanism, which makes the crisis visible through the culturally based visual grammar. Critically, it shows how the traditional forms tend to adapt to the contemporary socio-political exigencies, representing resilience without losing the aesthetic identity. Thus, the scroll exemplifies a hybrid space i.e., folk narrative techniques which collide with the global pandemic discourse.

4.3.4. Evolving Techniques and the Fusion of Indigenous and Western Artistic Elements

However, a transition from pre-colonial to post‑colonial Pattachitra is also marked by changes in artistic technique, patterns, and colour scheme. Consequently, Pattachitra artists in the past used earthy, natural pigments made from minerals and plants that gave the colour palette a unique subdued tone. However, these days, artists of modern Pattachitra use synthetic colours, and the composition becomes more saturated and highly contrasted (Mondal, 2022; Zanatta & Roy, 2021). In the first image, it can be seen that red, green, and yellow are much more vibrant than in earlier works, and commercial paints have replaced natural pigments.

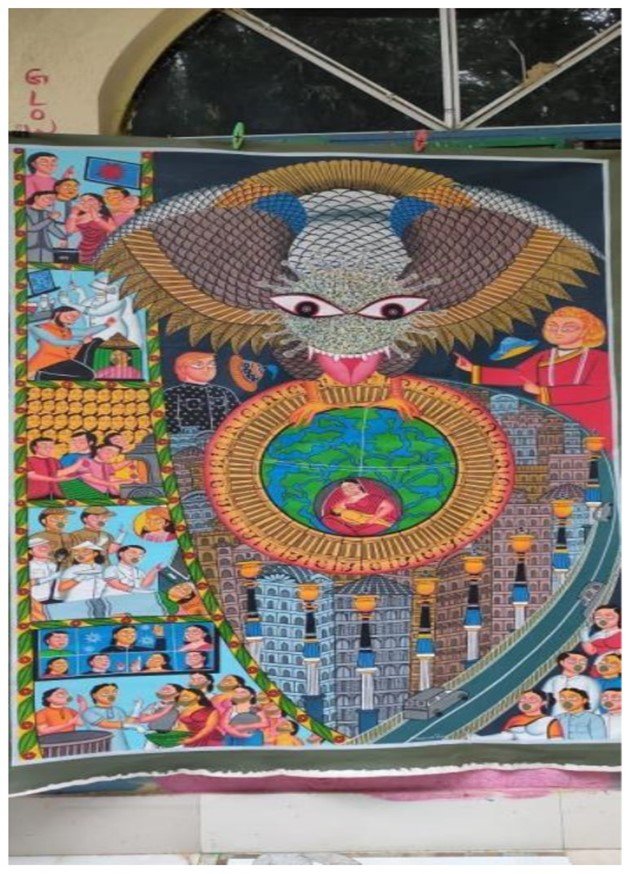

The other significant change has to do with the use of depth and layering. In classical Pattachitra, a flat linear perspective was followed wherein the elements were placed in a hierarchical order, not a spatial one. However, on 9/11, artwork does not follow this rule, overlapping buildings and figures/pictures to simulate the dimension of the space and movement. The COVID-19 scroll painting experiments in a similar vein with modern urban imagery (roads, cars, hospitals) draw upon the adaptation of Pattachitra’s composition to the context of the contemporary space. However, Fig. (10) by (Zanatta & Roy, 2021) also presented the incident of COVID-19, but this is different in pattern, including multiple aspects blending the modern and traditional contexts.

For example, Fig. (9) has one pathway in which a story is highlighted, starting from the initial virus. Social distancing from people, staying in their homes (complete lockdown); moving forward, the roads started having more vehicles, people coming out wearing masks, initially practising the social distancing in open areas then eventually returning to their life. However, the change persists, which is the mask on their faces. Now, the symmetry of the explanation was structured and streamlined in a flow; however, in contrast, Fig. (10) is layered. The monster at the start is the COVID-19 virus, and the different incidents have highlighted that the whole universe is under that specific monster's curse.

Then, on one side (left side), it highlighted how the people started facing issues of hunger, poverty, food depreciation, and then the influence of the army and doctors evacuating people under disease and leaving people speechless. On the right side, it can be seen that roads are emptying; the people in the pictures are quiet, representing some elites and others in society who are just watching people suffer and doing nothing. The buildings in between represent the vacant offices, reducing employment, shutting down businesses, and leading people to suffer for food and facilities. So, both figures use the same lighter tones, Indigenous representation, symbols, and related features, but the story's depiction is different in both.

This highlights the diversity of concepts and context within the art about the same incident but from different points of view. This is in line with the influence of post-colonials in West Bengal influencing the Pattachitra art, as patterns are also now narrative, especially when they are used to express narrative content such as British Influence, danger, and nasty trespassers from the dark side of nature. Floral motifs symbolise the viral spread in the pandemic scroll; rigid geometry in the 9/11 piece indicates a sense of oppression and modern chaos. This shift speaks of how Pattachitra has transitioned from being decorative folk art to a powerful tool for socio-political expression and cultural aspects in West Bengal.

Fig. (9). Folk artists in the time of coronavirus. Source: (Zanatta & Roy 2021; p149).

Early incorporations of European views and modelling had been seen in the colonial-era female portraits having an adaptive shading. These are some examples of ambivalent mimicry of Bhabha. However, they are not only an imitation. The "almost the same, but not quite" develops the visual slippage which unsettles the colonial authority i.e., the hybrid forms which speak back (Saha, 2021). While using the colonial techniques and repurposing them for critique, Pattachitra artists had reclaimed narrative control. Such strategic imbrication of foreign visual idioms hence, initiated the silent visual insurgency, which sowed hybridity. Later developing more overtly in the socio-political Pattachitras.

Fig. (10). Anwar Chitrakar, “Coronavirus”. ICCR award-winning scroll without Song acknowledgments to Anwar Chitrakar. Source: (Zanatta & Roy 2021; p151).

Conclusion

The colonial impact on the artistic traditions of Bengal had triggered a hybridisation, amalgamating Indigenous visual frameworks with European realism, views, and portrait techniques to align the art with colonial narratives. However, this imposition had never been one-directional. The artists had used mimicry as a type of cultural ambivalence, which enacts subtle resistance in “almost the same, but not quite” adaptation of the Western forms.

Referring to the post-colonial Bengal, Pattachitra evolved as a reclaimed as well as negotiated practice, and entered Bhabha’s “third space” that is a liminal arena which enabled negotiation between tradition including modernity artists had revitalised religious iconography such as Durga, changing her into a symbol of the feminist nationalist agency, whereas the global events such as 9/11 and covid‑19, had been rendered by the folk idiom as semiotic archives of the collective trauma.

All the narrative expansions underline Pattachitra’s resilience. The incorporation of traditional patterns with Western techniques developed a visually hybrid language that is capable of cultural commentary. The methodology i.e., a hybridity; informed visual framework, had facilitated the critical insights regarding how Pattachitra tends to negotiate gender, global issues, and identity with the use of compositional, chromatic, as well as thematic hybridity. Eventually, post-colonial Pattachitra exceeds its devotional origins towards becoming a vibrant cultural interlocutor which reflects Bengal’s emerging identity by an enduring, and hybrid artistic language evolving from the colonial encounter into the contemporary relevance and yet it has the potential to evolve more imbibing the essence of modernity which can be studied in the future.

Consent For Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data will be made available on reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author [S.B.].

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowlegdements

Declared none.

References

Anjana, S., & Savitha, A. R. (2023). Subverting patriarchal narratives: Exploring Bhyrappa's depiction of Sita through historiographic metafiction. The Grove Working Papers on English Studies, 30, 17–36. https://doi.org/10.17561/grove.v30.8022.

Awana, R. (2023). Homi K Bhabha (1949). All About Literature Net. https://allaboutliteraturenetin.wordpress.com/2023/08/05/homi-k-bhabha-1949 (Accessed July 9, 2025).

Baliga, A. R. (2016). The women artists of early 20th century Bengal: Their spaces of visibility, contributions, and the indigenous modernism. Doctoral dissertation, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Institutional repository.

Basak, B. (2011). The journey of Kalidas Datta and the construction of regional history in pre and post independent Bengal, India. Public Archaeology, 10(3), 132–158. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355311X13149692332295.

Basu, J. K. (2023a). Reviving tradition in contemporary storytelling: Visual and oral techniques in Sita's Ramayana and Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean. Managing Editor, 71.

Basu, P. (2022). Music and intermediality in trans border performances: Ecological responses in Pattachitra and Manasamangal. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 45(6), 1000–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2022.2121477.

Basu, R. (2023b). The Italian connection to Indian art in Calcutta. In Bengal and Italy: Transcultural encounters from the mid 19th to the early 21st century (1st ed., p. 20).

Bhabha, H. K. (2021). Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse. In Literary theory and criticism (pp. 171–181). Routledge India.

Chowdhury, A. D. (2022). Music as a medium in Patta Chitra—the scroll paintings of Bengal. Sangeet Galaxy, 11(2), 61.

Datta, A. (2018). Through the eyes of an artist: Consumption ethos and commercial art in Bengal. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 10(3), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-03-2018-0014.

Deb, B. (2022). The role of philately in art storytelling: The case of Ramayana. In 10th International Digital Storytelling (pp. 1–8). Loughborough University.

Deb, M. (2021). Manifestation of icon in the idol of Goddess Durga in Bengal during the pre independent and post independent period. In The making of Goddess Durga in Bengal: Art, heritage and the public (pp. 85–112). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0263-4_4.

Dey, A. (2023). Historicising marginality in graphic narratives: India and beyond. An International Multidisciplinary Research e Journal, 10(3), 6–26.

Iqbal, H. M. Z., & Rehan, N. (2020). Ambivalent colonial encounters: A post-colonial rereading of Mircea Eliade’s Bengal nights. Pakistan Social Sciences Review, 4(2), 32–43.

Kalplata. (2025). Framing postmodern Sita in Sita: Daughter of the Earth. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2025.2462662.

Katiyar, B. S. (2019). Historical ornamentation of ancient narrative scroll painting tradition of China, Japan, and India. International Advance Journal of Engineering, Science and Management (IAJESM), 12(1), 60–66.

Kaviraj, S. (2003). The two histories of literary culture in Bengal. In Literary cultures in history: Reconstructions from South Asia (pp. 50–366). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520926738-013.

Majumder, S., & Banerjee, S. (2024). The hybridity of Pattachitra Katha media: The folk pop art narrative tradition of Bengal. AJBMSS.

McMullen, L. (2021). Double colonisation: Femininity and ethnicity in the writings of Edith Eaton. In Crisis and Creativity in the New Literatures in English: Canada (pp. 141–151).

Mitter, P. (2008). Decentering modernism: Art history and avant garde art from the periphery. The Art Bulletin, 90(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2008.10786408.

Mokashi, A. (2021). Pattachitra: The heritage art of Odisha. Peepul Tree. https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindia/story/living-culture/pattachitra (Accessed March 12, 2025).

Mondal, S. A. (2022). Discourse on Pattachitra art with narratives and songs in the religious and cultural scenario of West Bengal.

Mondal, S., & Bhattacharjee, S. (2024). An exploration of the nuances of Pattachitra and the identity of the Patua in colonial and post-colonial Bengal. Disciplining the Temporalities, 46.

Musa, E. I. B. (2021). Formulation of visual narrative reading and coding approach through cultural waterfront portraiture photographs analysis.

Nasrullah, M. (2016). Mimicry in post-colonial theory. Literariness. https://literariness.org/2016/04/10/mimicry-in-post-colonial-theory/comment-page-1 (Accessed July 9, 2025).

Pratha Cultural School (2025). A glimpse into the Pattachitra paintings of Orissa | Pratha. https://www.prathaculturalschool.com/post/a-glimpse-into-the-pattachitra-paintings-of-orissa (Accessed March 12, 2025).

Rahman, A., Ali, M., & Kahn, S. (2018). The British art of colonialism in India: Subjugation and division. Peace and Conflict Studies, 25(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.46743/1082-7307/2018.1439.

Rohila, B. (2023). Graphic novels and traditional art forms: The Indian context. Indialogs, 10, 11–26. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.218.

Rukundwa, L. S., & Van Aarde, A. G. (2007). The formation of post-colonial theory. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 63(3), 1171–1194. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v63i3.237.

Saha, A. (2021). An investigation into the principle of gender flexibility via selected narratives from North Bengal.

Sethi, B. (2023). Cultural sustainability: Influence of traditional craft on contemporary craft cross culturally.

Sinha, D., & Ali, Z. (2024). From Agni to Agency: Sita’s liberation in Arni and Chitrakar’s graphic retelling of the Ramayana. Humanities, 13(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13040097.

Spencer, S. (2022). Visual analysis. In Visual Research Methods in the Social Sciences (pp. 194–236). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203883860.

Zanatta, M., & Roy, A. G. (2021). Facing the pandemic: A perspective on Pattachitra artists of West Bengal. Arts, 10(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030061.

Licensed

© 2025 Copyright by the Authors.

Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.

Article Contents Author Yazeed Alsuhaibany1, * 1College of Business-Al Khobar, Al Yamamah University, Saudi Arabia Article History: Received: 03 September,

Article Contents Author Muhammad Arslan Sarwar1, * Maria Malik2 1Department of Management Sciences, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan; 2COMSATS

Article Contents Author Tarig Eltayeb1, * 1College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Kuon Keong Lock1, * and Razali Yaakob1 1Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia,

Article Contents Author Shabir Ahmad1, * 1College of Business, Al Yamamah University, Al Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Ghanima Amin1, Simran1, * 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Sialkot, Sialkot 51310, Pakistan Article History: Received:

PDF

PDF