Article Contents

Article ID: CM2611101001

The Dark Side of International Talent Management: Exploring the Negative Effect of Talent Repatriation on Multinational Enterprises Performance with the Meditating Role of Reverse Culture Shock

⬇ Downloads: 11

Cite

AboAlsamh, H. M. (2025). The dark side of international talent management: Exploring the negative effect of talent repatriation on multinational enterprises’ performance with the mediating role of reverse culture shock. Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.65080/942npc70

AboAlsamh, Hoda Mahmoud. 2025. “The Dark Side of International Talent Management: Exploring the Negative Effect of Talent Repatriation on Multinational Enterprises’ Performance with the Mediating Role of Reverse Culture Shock.” Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences 1 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.65080/942npc70

AboAlsamh, H.M., 2025. The dark side of international talent management: Exploring the negative effect of talent repatriation on multinational enterprises’ performance with the mediating role of reverse culture shock. Advances Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), pp.1–9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.65080/942npc70

AboAlsamh HM. The dark side of international talent management: Exploring the negative effect of talent repatriation on multinational enterprises’ performance with the mediating role of reverse culture shock. Adv J Bus Manag Soci Sci. 2025 Feb 7;1(1):1–9. doi:10.65080/942npc70

1College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

Received: 29 October, 2024

Accepted: 30 January, 2025

Revised: 25 January, 2025

Published: 07 February, 2025

Abstract:

Aims and Objectives: This study explored the negative effects of talent repatriation on multinational enterprise (MNE) performance, focusing on the mediating role of reverse culture shock. Even as international assignments were planned and implemented with the idea of building global talent and organisational global knowledge, repatriation presents a couple of key problems that work against such a value addition.

Methods: The study explored talent repatriation and reverse culture shock with the MNE performance through survey questionnaire distributed to 385 employees working in MNEs who were returned to their home country following an international assignment. The participants were recruited across technology, business, medical, engineering and IT companies of the UK. The data was analysed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM).

Results: According to the research results, the author concludes that while talent repatriation has had no direct effects on the performance of MNE (B = 0.066, p-value = 0.393), reverse culture fully mediates the relationship between talent repatriation and MNEs performance (B = 0.287, p-value = 0.000). This implies that reverse culture shock plays a key role in mediating the influence of the repatriation processes in its contribution to the performance of the MNE.

Conclusion: It underscores the importance of MNEs to develop repatriation policies that respond to logistics, career, psychological and cultural aspects resulting from the relocation.

Keywords: Talent management, MNEs, culture shock, repatriation, organizational performance, PLS-SEM.

1. Introduction

Multinational enterprises operating in the modern business environment draw heavily on international human capital mobility to boost global competitiveness and foster a talent pool with intercultural accolades (Shah & Baber, 2023). These expatriate assignments are fundamental to talent management and creating and sharing expertise inside a company. This, in turn, leaves out one significant area in international talent management – repatriation, where the employee moves back to their home country after working in another country. Although expatriation is viewed as career mobility, more so as having a positive impact on the career biography of the employee, repatriation turns out to be a problem that negatively impacts the worker and the organisation (Collings & Isichei, 2017). Returning to the company can be disheartening for many repatriated employees; reverse culture shock affects their working performance.

Reverse culture shock is the process whereby employees, having adapted to the host country’s culture must readjust to the culture and organisational changes of their home country (Latukha et al., 2019). This often results in feelings of isolation, dissatisfaction and perceived low organisational value, which may translate into low job performance and high turnover rates. Reverse culture shock and defective repatriation procedures are a severe but not thoroughly explored issue in international human resource management, especially among UK-based MNEs. Returning expatriates frequently have difficulties reintegrating into their home country’s organisational culture, experiencing lower job satisfaction, disengagement, and even early termination (Liu, 2024). This disconnection has the potential to deny UK MNEs full leverage of the world skills and knowledge their expatriates gain overseas (Glencross, 2023; Pasmatzi, 2022). Even though expatriation has been a subject of much research from the studies such as (Hack-Polay & Mahmoud, 2023; Helminen, 2025; Lo & Nguyen, 2023; Ribeiro & Silva, 2025; and Zhong et al., 2021), the repatriation process, and particularly the mediating effect of reverse culture shock on organisational performance, still remains underexplored.

This research targets the UK in particular, where new socio-political developments like Brexit, changing immigration policies, and the growing necessity for global competitiveness have heightened the need for successful international talent management (Pasmatzi, 2022; Read & Fenge, 2019). British MNEs are under increased pressure to hold onto globally experienced managers and bring their repatriation policies in line with changing economic and cultural realities (Glencross, 2023). It is timely and necessary to do this research now as British companies aim to consolidate and maximise their international activity in a post-Brexit environment. The research will benefit HR professionals, business executives, and policy-makers by providing an understanding of the normally neglected repatriation stage of global assignments. The research will underscore the need for managing reverse culture shock as a mediating process that can be a hindrance or an addition to organisational performance. By bridging this research gap, the research adds to more strategic and evidence-based management of talent retention and reintegration and hence firms’ global capability and competitiveness of UK MNEs.

2. Literature Review

Talent repatriation and its implications for MNEs have been studied in the international business context literature paradigm as organisations look for a global talent pool for a competitive edge. While expatriate management has witnessed steady research attention, the process of repatriation, which is almost equally strategic to organisational productivity and the retention of key human capital, has received scarce attention (Shah & Baber, 2023). This literature review delves into three key areas relevant to the study: talent turnover, reverse culture shock and its implication on multinational enterprise performance.

2.1. Talent Repatriation: Challenges and Organisational Implications

Talent repatriation is when employees are returned to their home country from an international assignment location (Nag & Malik, 2023). This is commonly regarded as one of the most important stages of talent management in MNEs. Still, often, it needs to be managed more unsystematically in comparison with the process of eviction. (Howe-Walsh & Torka, 2017) emphasised that repatriation includes certain difficulties for an employee and the organisation, namely unfulfilled career expectations, non-use of international experience, and organisational support. The difference between what was expected and what is being experienced creates dissatisfaction, which may cause low motivation and sometimes employee turnover (James & Azungah, 2020; Minbaeva et al., 2025). These challenges confirm that most MNEs need to establish an official sequence of repatriation programs, which costs them talented professionals and undermines their competitive capabilities in markets.

Employees who have returned from an international posting often report that they need to be tapped to their full potential, and the skills they have developed abroad are not fully utilised (Chanda & Betai, 2021). This lack of recognition can cause low job satisfaction, resulting in job dissatisfaction, employee withdrawal, and actual turnover, as statistics indicate that many returned international employees terminate their contracts within one year of repatriation (Trinh, 2023). This disagreement may also raise feelings of isolation and dissatisfaction that they were not given what they expected upon returning to their home country. Consequences of failed management of the repatriation process are that great talents are lost from the company, employee morale is low, and the process of knowledge transfer is compromised, consequently damning the competitiveness and innovation of the company (Sreeleakha, 2014). To address these concerns, organisations have to enhance the strategy of repatriate management, and they need to include career progression, job descriptions and the psychological state of the escorting employees into their repatriation policies.

2.2. Reverse Culture Shock: A Barrier to Reintegration

(Moonsup & Pookcharoen, 2017) explained that, like in culture shock experienced during expatriation, expatriates might experience reverse culture shock when they again find themselves in their home country and organisational climate. Although the study identified reverse culture shock upon repatriation, yet their study lacks focus on its mediating impact on organisational performance. While providing valuable insights, it is limited for its generalisation and lacks specific application to MNEs of UK. (Al-Krenawi & Al-Krenawi, 2022) postulated that reverse culture shock may cause emotional and psychological problems to the employees since they do not fit into the organisational culture of their home country. The study effective focus on emotional impacts of reverse culture shock, yet overlook its organisational implications. The strength of this study is in addressing psychological wellbeing; however, it lacks empirical focus on how such challenges affect organisational performance, specifically in the UK MNEs. (Latukha et al., 2019) indicated that the disparity in cultural shock commonly results in loneliness, unrest, and the impression that the organisation underestimates the personnel. Since there is a lack of support during this phase, the lifestyles of repatriated employees may lead to job climate, which is a determinant factor in job performance and productivity. The study highlighted the emotional toll of reverse culture shock and its effect on perceived organisational support. However, the study lacks a clear link between job climate and organisational performance. Its strength lies in identifying employee experience, limitations include limited contextual focus. (Nag & Malik, 2023) explained that if the effects of reverse culture shock are left unchecked, organisations will continue experiencing high turnover, losing talent and hence low productivity for the organisation; it is therefore very important for organisations to ensure that they continue to offer support, counseling and career development for the reverse shock affected individuals. The study highlights the importance of support mechanisms for reducing turnover from the reverse culture shock. However, the study lacks quantitative evidence linking such support to performance outcomes. Its strength includes practical guidance. Yet, it’s limited due to the absence of empirical validation.

2.3. Impact on Talent Repatriation on Multinational Enterprises' Performance

Empirical work on talent repatriation indicates increasing recognition of its effects on organisational performance, yet with considerable gaps. (Shah & Baber, 2023) highlighted the significance of organisational repatriation support practices in maintaining global talent. Their work, while rich in terms of concepts, is lacking empirical evidence and does not attempt to examine the direct impact of the lack of such practices on organisational results, particularly in certain national contexts such as that in the UK. In a similar vein, (Ho et al., 2024) analysed turnover intentions of 445 Vietnamese self-initiated repatriates with the help of structural equation modeling (SEM). They identified that adjustment challenges, both in professional and life settings, enhance turnover intentions, thus inferring adverse effects on organisational productivity. Their research is only confined to Vietnam and does not consider more wide-ranging organisational performance indicators or implications in developed economies.

(Valk, 2022) investigated international talent management using qualitative interviews among 78 expatriates and repatriates from different countries. Underlying a mismatch between organisational and repatriates’ career objectives was the underutilisation of talent. Even though the findings provide in-depth qualitative insight, they are self-reports and do not include direct measurement of organisational outcomes. (Kudo et al., 2024) carried out a phenomenological investigation of 20 Ghanaian organisationally assigned scholars and identified that repatriation decisions are taken halfway through the assignment with a bias for the absence of continuous support. Although the research enlightens on an overlooked population, scholar expatriates, there is no empirical examination of how these decisions influence organisational performance.

Lastly, (Fuchs & Primecz, 2025) presented a new view by incorporating repatriates and HR practitioners into the analysis. In their research, they brought forth the idea of a “buffering effect,” in which perceived organisational support counters the adverse effects of decreased repatriation support. They claimed that convergence between personal expectations and organisational support increases retention and knowledge transfer. Although useful, the research relies only on ten interviews and has not received large-scale testing.

These studies highlight the significance of successful repatriation for talent retention and organisational effectiveness. Yet, significant research gaps still remain, most notably the absence of empirical evidence connecting repatriation practice directly to organisational performance, under-research into the mediating influence of reverse culture shock, and a deficit of research within the UK setting. Although strengths in such studies are found in their investigation of psychological and strategic aspects of repatriation, they are usually brought down by small samples, regional context, and lack of multi-stakeholder data.

The results throughout these studies can be challenged under Social Exchange Theory (SET), which suggests that workers respond to organisational support with commitment and performance (Peltokorpi et al., 2021). Although numerous studies indicate repatriates’ emotional and professional challenges, they are insufficient to demonstrate how poor support breaks the reciprocal relationship, causing talent loss and decreased performance. For example, (Shah & Baber, 2023; and Valk, 2022) recognise repatriate underutilisation but neglect how this psychological contract violation dissolves loyalty. Furthermore, most research does not have longitudinal data to evaluate the influence of sustained organisational support, as proposed by SET, on long-term retention and performance. Hence, it can be hypothesised that;

2.4. Mediating Role of Reverse Cultural Shock

Reverse culture shock acts as a mediating force linking talent repatriation to organisational performance by determining how well repatriated employees are able to reintegrate and perform after return. Under Social Exchange Theory (SET), when organisations invest in their employees via repatriation support, career planning, and psychological support, employees tend to respond with greater commitment and performance (Lehtonen et al., 2023). Reverse culture shock, however, interferes with the exchange by inducing disorientation, dissatisfaction, and disengagement that dilute the desired organisational gains from repatriation (Roberts et al., 2025).

Organisational Support Theory (OST) also adds to this by positing that perceived organisational support reduces the adverse impact of reverse culture shock, enabling repatriates to reintegrate better and share their global competencies (Kumar et al., 2022). Lacking such support, repatriates can feel isolated or devalued, which results in lowered morale, increased turnover, and underuse of acquired skills, ultimately undermining organisational performance (Heikkinen, 2021). Despite recognition of the emotional and cultural difficulties of repatriation in the literature such as (Gao et al., 2023; James, 2021; and Zavala-Barajas et al., 2022), few actually test reverse culture shock mediating effects quantitatively. Based on the theoretical support, the study hypothesised that;

2.5. Conceptual Framework

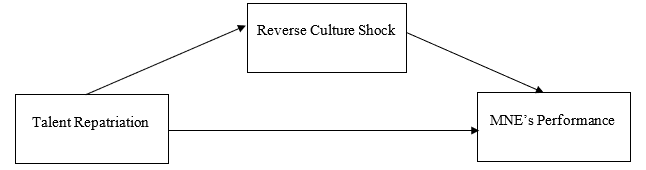

Fig. (1) represents the conceptual framework of the study. It shows the impact of talent repatriation on the MNE’s performance. The relationship between these variables has been established under the study of (Ho et al., 2024; Valk, 2022; and Fuchs & Primecz, 2025) that have emphasised that the talent repatriates are under-utilised in the organsiations leading to their turnover and lower satisfaction. It leads to the impact on the performance of the employees and company as a whole. Furthermore, the mediating role of reverse cultural shock is indicated in the framework which is supported from the SET and OST which investigates that reverse cultural shock interferes in the process of effective talent repatriation and hence disrupts the organisation performance as well (Roberts et al., 2025).

Fig. (1). Conceptual Framework.

2.6. Literature Gap

Even after growing emphasis on international talent management, much is left to be understood regarding the adverse impact of talent repatriation on the performance of MNEs. Current empirical research mostly concentrates on repatriates’ individual experience, emotional adjustment, and turnover intention (Ho et al., 2024; Kudo et al., 2024), but they are unable to connect repatriation directly with organisational performance outcomes. Further, the mediational role of reverse culture shock, while recognised as a psychological obstacle, is seldom investigated under quantitative frameworks. Most research such as (Valk, 2022; and Shah & Baber, 2023) are focused on the support gap but provides few insights into how this asymmetry translates into reduced strategic benefit for MNEs. The existing literature is also predominantly focused on developing or transition economies with little research carried out in the context of the UK.

3. Methodology

The present study uses a quantitative research method, which is appropriate when analysing talent repatriation, reverse culture shock and the performance of MNEs. Sampling is accomplished using the survey method so that the study focuses on systematically gathering data and assessing the impact of leadership and career development from the perceptions and experiences of the repatriated employees in a stated generalisable way across different organisations and industries. A cross-sectional research design was used to test the mediating effect of reverse culture shock between talent repatriation and MNE performance. This approach enables data collection at one given time thus enhancing the evaluation of the effect of different variables in a large population of repatriated employees. A five-points Likert scale questionnaire (Appendix) was designed to measure the respondents’ attitudes, experiences, and perceptions towards talent repatriation, reverse culture shock and its impact on MNE performance. Closed-ended questions are used for the survey to reduce variance in answers and allow for the analysis of responses numerically (Yaro et al., 2023). The final construct questionnaire was composed of questions including different sections based on the research objectives, based on a 5 Likert scale, which ranged from Strongly Disagree = 1 to Strongly Agree = 5, regarding individual questions that were established on talent repatriation, reverse culture shock, and organisational performance.

The target population for this study included employees working in MNEs who have returned to their home organisation following an international assignment. Participants were drawn from diverse sectors that include technology, business, medical, engineering and IT companies of the UK. The representation ensured broad relevance and applicability of the research findings. The cross-sectoral inclusion increases the generalisability of the findings in different segments of the economy. The study has used purposive sampling method to specifically target individuals with direct experience of repatriation, that enriches study’s validity. The participants were approached through LinkedIn, and personal contacts to ensure that the platforms to approach participants were diverse so that there is no concern of selection bias occurring due to the use of purposive sampling. This technique to remove selection bias is consistent with the study of (Bell-Martin, & Marston, Jr., 2021).

The survey was distributed to 650 participants where only 405 responses were received attaining a response rate of 62%. The responses were then filtered for the missing values where 11 missing values were removed having the sample of 394. The responses were then filtered for the detection of outliers based on the Z-score method as explained by (Yaro et al., 2023). The value of Z > 3 were considered as outliers. 9 values were detected as outliers providing the final sample of 385.

However, the lower response rate of 62% increases the concern on the non-response bias which needs to be addressed. The non-response bias was addressed in this study by evaluating the statistical difference between the early and late respondents. The late respondents have a similar characteristic to the non-respondents and hence it provides effective method to address such issues (Clarsen et al., 2021). Hence, the early respondents (n1 = 30) and late respondents (n2 = 30) were compared through independent sample t-test. The results highlighted that construct such as talent repatriation (P-value > 0.1), MNE’s performance (P-value > 0.1), and Reverse cultural shock (P-value > 0.1) have insignificant difference between early and late respondents. Therefore, the data is indicated to be free from the non-response bias.

The use of similar method for measuring dependent and independent variable (Likert Scale questionnaire) introduces the research to the common method bias as well (Baumgartner et al., 2021). The common method bias can be reduced in this study using Harman’s single factor test, where exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is conducted to extract only single factor and the total variance explained for that single factor falling below 50% shows that the common method bias does not exist (Bozionelos & Simmering, 2022). For this research, the EFA indicated total variance extracted below 45% and hence the common method bias was not detected in this study.

To enhance the internal validity and reliability of the survey, the questions were piloted among a small number of respondents with the aim of identifying general levels of understating of the questions and clearing any difficulties that might be encountered in understanding the questions. The information gathered during the survey was analysed with the help of SMART PLS – a suitable instrument for modeling the relations between the variables, in case the sample size is moderate and the research model contains various constructs with potential mediating effects.

The study was conducted based on several ethical principles as a guideline. The participants read and signed informed consent forms before completing the surveys and were told that the results would be kept anonymous. Respondents were fully informed about the survey, and there was no participation coercion; they were free to withdraw at any date. To maintain the anonymity of the participants, all data were coded, conforming to data protection regulations.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the demographics of the 385 respondents. The large majority were male (86%) and only 14% female, possibly reflecting male-dominated fields like engineering and IT. Participants were predominantly 31–35 years old (35%), followed by those aged 26–30 (25%), representing a fairly youthful and mid-career population. Education-wise, 58% of them had postgraduate qualifications, representing a range of very well-educated participants. Work experience statistics indicate that 47% had 1–5 years in their organisation, with 29% having less than a year, indicating a high percentage of fairly new or newly repatriated employees, pertinent to examining repatriation dynamics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

| Demographic Category | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 331 | 86% |

| Female | 54 | 14% | |

| Age | up to 25 | 39 | 10% |

| 26-30 | 96 | 25% | |

| 31-35 | 135 | 35% | |

| 35-40 | 65 | 17% | |

| 40+ | 50 | 13% | |

| Education | Under graduate | 142 | 37% |

| Post graduate | 223 | 58% | |

| Doctoral | 19 | 5% | |

| Years of Experience in current company | less than a year | 112 | 29% |

| 1-5 years | 181 | 47% | |

| More than 5 years | 92 | 24% |

Table 2 shows the measurement model using Confirmatory factor analysis. It reflects the factor loadings to evaluate the validity of the indicators where value of factor loadings above 0.6 is considered to be valid (Brown & Moore, 2012). The value of factor loadings in below tables are greater than 0.6 showing that there is no need to drop any indicator and hence the indicators are valid in measuring the constructs. The table also shows the value of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability to measure the internal consistency and reliability of the constructs. The value of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability above 0.7 indicates the internal consistency and reliability of the constructs (Hox, 2021). The value of composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha for each variable below is greater than 0.7 confirming that each of the constructs are reliable. Furthermore, AVE is used to evaluate the convergent validity of the constructs where value above 0.5 indicates that the constructs have convergent validity (dos Santos & Cirillo, 2023). AVE for each of the construct below is above 0.5 confirming convergent validity.

Table 2. Measurement model using CFA.

| Latent Constructs | Indicators | Factor Loadings | Cronbach's alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNE Performance | MNEP1 | 0.834 | 0.896 | 0.907 | 0.661 |

| MNEP2 | 0.853 | ||||

| MNEP3 | 0.873 | ||||

| MNEP4 | 0.856 | ||||

| MNEP5 | 0.752 | ||||

| MNEP6 | 0.693 | ||||

| Reverse Culture Shock | RCS1 | 0.834 | 0.908 | 0.911 | 0.686 |

| RCS2 | 0.859 | ||||

| RCS3 | 0.813 | ||||

| RCS4 | 0.817 | ||||

| RCS5 | 0.822 | ||||

| RCS6 | 0.821 | ||||

| Talent Repatriation | TR1 | 0.781 | 0.855 | 0.861 | 0.580 |

| TR2 | 0.803 | ||||

| TR3 | 0.765 | ||||

| TR4 | 0.672 | ||||

| TR5 | 0.787 | ||||

| TR6 | 0.755 |

The discriminant validity is further evaluated using HTMT ratio as shown in Table 3. As per (Brown & Moore, 2012), HTMT ratio below 0.85 indicates that constructs are discriminant valid and they are unrelated to each other. HTMT ratios as shown in Table 3 are below 0.85 showing that the discriminant validity is confirmed. Hence, the measurement model confirms that the constructs and indicators are valid and reliable.

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

| MNE Performance | Reverse Culture Shock | |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Culture Shock | 0.520 | |

| Talent Repatriation | 0.401 | 0.734 |

Table 4 indicates the structural model. It shows that Talent repatriation (B = 0.066, p-value = 0.393) have insignificant and positive direct impact on MNE performance. However, indirect effect of talent repatriation (B = 0.659, p-value = 0.000) on MNE performance is significant and positive. The specific indirect effect shows that reverse cultural shock (B = 0.287, p-value = 0.000) shows positive and significant mediating effect on the relationship between talent repatriation and MNE performance. It confirms the full mediation of reverse cultural shock on the relationship between talent repatriation and MNE performance.

Table 4. Structural model.

| Path | Path Coefficient | T statistics | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Culture Shock -> MNE Performance | 0.435*** | 5.364 | 0.000 |

| Talent Repatriation -> MNE Performance | 0.066 | 0.853 | 0.393 |

| Talent Repatriation -> Reverse Culture Shock | 0.659*** | 21.088 | 0.000 |

| Indirect Effect | |||

| Talent Repatriation -> MNE Performance | 0.287*** | 5.390 | 0.000 |

| Specific Indirect Effect | |||

| Talent Repatriation -> Reverse Culture Shock -> MNE Performance | 0.287*** | 5.390 | 0.000 |

Note: *** indicates significance at 1% level, ** indicates significance at 5%, * indicates significance at 10%

5. Discussion

The research was conducted to evaluate the impact of talent repatriation on the MNE performance along with the mediating role of reverse cultural shock especially considering the context of the UK. The results of the structural model show an interesting pattern between the relationship between talent repatriation and MNE performance. Although the direct relationship between talent repatriation and MNE performance is statistically not significant, the indirect relationship through reverse culture shock is significant and positive. This indicates a complete mediation; whereby reverse culture shock plays a significant part in bridging the effect of repatriation to concrete organisational outcomes. Such findings differ from existing research like (Shah & Baber, 2023; and Ho et al., 2024), which highlighted the strategic benefits of repatriated talent and its presumed direct impact on organisational performance. Yet they failed to empirically examine the mediating function of reverse culture shock. Likewise, (Valk, 2022; and Fuchs & Primecz, 2025) identified underutilisation and misalignment problems but did not have a structural link or mediation model to account for how repatriation affects MNE performance through psychological and cultural adjustment processes.

The difference in findings could be attributed to contextual variations. For the UK context, within which this study is located, organisational cultures could be less adaptive or responsive to the reintroduction of globally experienced workers. UK MNEs could also not have well-established repatriation support systems, and thus repatriates could be more intensely exposed to reverse culture shock, which impacts their involvement, job satisfaction, and performance levels (Glencross, 2023). This would be the reason why the indirect route, mediated by reverse culture shock, is the prevailing channel through which repatriation affects performance.

In addition, the UK’s post-Brexit economic environment and rising international mobility have made repatriation experiences more complicated, usually amplifying cultural dissonance and expectation failures. This underlines UK MNEs’ necessity to acknowledge and manage reverse culture shock actively to translate overseas experience into performance improvements. The results emphasise the strategic importance of focused reintegration policies and psychological support structures.

Conclusion

This research concludes that whereas talent repatriation in itself does not significantly contribute to MNE performance, its indirect effect, through the mediation of reverse culture shock, is significant and substantial. This underscores the importance of psychological and cultural adaptation in bringing about the desired gains from international talent mobility. Within the UK context, the lack of formal repatriation support exacerbates reverse culture shock, nullifying the potential for improving performance by returning employees.

It is suggested that UK-based MNEs formulate extensive repatriation programs covering pre-return briefings, post-return career planning, and psychological support to effectively manage reverse culture shock. HR departments should also play an active role, staying in touch during international assignments and implementing clear reintegration strategies. By treating reverse culture shock as a strategic issue, companies are able to retain returned talent more effectively and utilise their global experience to stimulate innovation, develop leadership, and enhance organisational performance.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION

This research has a number of limitations. Although the sample size was adequate (n = 385), it was restricted to those respondents who could be contacted through LinkedIn and email, thus leaving out less digitally active professionals. The research considered only the UK context, which could limit generalisability to other cultural or institutional contexts. Moreover, cross-sectional design limits causal inference between variables over time. Furthermore, the study has considered limited variables and other psychological and cultural variables needs to be integrated in this research to evaluate the context in a much broader aspect.

Subsequent studies must utilise longitudinal designs to monitor repatriates’ experience and performance outcomes over time. Widening the study to other nations or regions would provide comparative insights into the role of national culture and organisational practices on repatriation outcomes. Additionally, the use of qualitative interviews could add depth to understanding the complex experiences of repatriates and reintegration problems, giving rise to more specific and responsive HR policies to manage global talent. The future researchers can also use other mediating psychological and cultural factors to broaden the findings.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The results of this research have significant policy implications for UK-based MNEs. The strong mediating effect of reverse culture shock implies that repatriation needs to be considered as a strategic stage of global talent management, rather than a routine administrative procedure. HR policies must require formal repatriation programs, such as pre-return preparation, psychological counseling, career planning, and continuing support upon return. Organisations need to institutionalise monitoring systems to evaluate repatriates’ adjustment and participation after return, such that their global experience is successfully transferred back into organisational processes. The performance appraisal systems also need to be able to recognise and reward global abilities developed overseas to foster retention and motivation. National policy organisations and professional HR organisations in the UK also need to create guidelines and toolkits to assist MNEs in standardising repatriation policies. The adoption of such policies will decrease talent attrition, increase organisational performance, and optimise the ROI of international assignments.

Consent For Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data will be made available on reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author [H.M.A.].

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowlegdements

Declared none.

APPENDIX: SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

Gender

a) Male

b) Female

a) Up to 25

b) 26-30

c) 31-35

d) 36-40

e) 40+

a) Undergraduate

b) Postgraduate

c) Doctoral

a) Less than 1 year

b) 1-5 years

c) More than 5 years

1) Strongly disagree 2) Disagree 3) Neutral 4) Agree 5) Strongly agree

SURVEY

Section 1: Talent Repatriation

- 1. The repatriation process is not managed well by the organisation.

- 2. The company does not support employees returning from international tasks.

- 3. I feel that repatriation negatively impacted my career progression.

- 4. The repatriation process lacks clarity and causes confusion among returning employees.

- 5. The organisation does not reward and recognises the value of my international experience.

- 6. The concern has been raised on the low awareness level about the general duties of the returning employees among others.

Section 2: Reverse Culture Shock

- 7. I experienced challenges adapting to the company's culture after returning.

- 8. I felt isolated from my colleagues after repatriation.

- 9. My expectations regarding my role upon return were not met.

- 10. The organisation did not prepare me for the psychological challenges of reverse culture shock.

- 11. My professional expectations were not met, causing frustration and dissatisfaction. Reverse culture shock has made it challenging to adapt to my role and responsibilities.

Section 3: MNEs Performance

- 12. Talent management in this organisation has also been affected through poor repatriation thus leading into loss of talent.

- 13. High turnover of repatriated employees has negatively impacted the organisation’s performance.

- 14. Lack of proper management on the repatriation has therefore led to negative impacts on its productivity.

- 15. The organisation has become less competitive in the international market because of absence of a structured repatriation program.

- 16. Decreased morale of employees after repatriation has resulted in lower team performance.

- 17. There’s been a decline in financial performance due to some factors that have be set the organisation’s repatriated employees.

References

Al-Krenawi, A., & Al-Krenawi, L. (2022). Acculturative stress and reverse culture shock among international students: Implications for practice. Arab Journal of Psychiatry, 33(1). https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A1%3A5836145/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A157235754&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com.

Baumgartner, H., Weijters, B., & Pieters, R. (2021). The biasing effect of common method variance: Some clarifications. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49, 221-235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00766-8.

Bell-Martin, R. V., & Marston Jr, J. F. (2021). Confronting selection bias: The normative and empirical risks of data collection in violent contexts. Geopolitics, 26(1), 159-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1659780.

Bozionelos, N., & Simmering, M. J. (2022). Methodological threat or myth? Evaluating the current state of evidence on common method variance in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(1), 194-215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12398.

Brown, T. A., & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. Handbook of structural equation modeling, 361, 379. https://books.google.com.pk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=P16bEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA261&dq=factor+loadings+and+confirmatory+factor+analysis&ots=jzekxlaxcI&sig=e18Fc1OdFJWtbURgMVs0mGip2qQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=factor%20loadings%20and%20confirmatory%20factor%20analysis&f=false,

Chanda, R., & Betai, N. V. (2021). Implications of Brexit for Skilled Migration from India to the UK. Foreign Trade Review, 56(3), 289-300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0015732521101220.

Clarsen, B., Skogen, J. C., Nilsen, T. S., & Aarø, L. E. (2021). Revisiting the continuum of resistance model in the digital age: a comparison of early and delayed respondents to the Norwegian counties public health survey. BMC Public Health, 21, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10764-2.

Collings, D.G. & Isichei, M., (2017). Global talent management: what does it mean for expatriates?. In Research handbook of expatriates. (pp. 148-159). Edward Elgar Publishing. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784718183.00016.

dos Santos, P. M., & Cirillo, M. Â. (2023). Construction of the average variance extracted index for construct validation in structural equation models with adaptive regressions. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 52(4), 1639-1650. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2021.1888122.

Fuchs, A., & Primecz, H. (2025). From expatriates to homecoming heroes–balancing organizational interests and support for a facilitated repatriation. Journal of Global Mobility, 13(2), 179-197. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-09-2024-0097.

Gao, L., Luo, X., Yang, W., Zhang, N., & Deng, X. (2023). Relationship between social support and repatriation intention of expatriates in international construction projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 30(8), 3292-3309. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2021-0931.

Glencross, A. (2023). The origins of ‘cakeism’: The British think tank debate over repatriating sovereignty and its impact on the UK’s Brexit strategy. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(6), 995-1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2072371.

Hack-Polay, D., & Mahmoud, A. B. (2023). Beyond culture shock: entering the complex world of Global South expatriates’ adaptation. Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/CIX9Q0.

Heikkinen, E. (2021). Repatriation adjustment and organizational repatriation support practices among long-term assignees. https://osuva.uwasa.fi/handle/10024/13230.

Helminen, C. (2025). Well-being of Self-Initiated Expatriates: Exploring Work-related and Non-work-related Factors. https://osuva.uwasa.fi/handle/10024/19621.

Ho, N.T.T., Hoang, H.T., Seet, P.S. & Jones, J., (2024). Navigating repatriation: factors influencing turnover intentions of self-initiated repatriates in emerging economies. International Journal of Manpower, 45(5), pp.999-1018. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2023-0122.

Howe-Walsh, L. & Torka, N., (2017). Repatriation and (perceived) organisational support (POS) The role of and interaction between repatriation supporters. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 5(1), pp. 60-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-09-2016-0040.

Hox, J. J. (2021). Confirmatory factor analysis. The encyclopedia of research methods in criminology and criminal justice, 2, 830-832. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119111931.ch158.

James, R. & Azungah, T., (2020). Repatriation of academics: organizational support, adjustment and intention to leave. Management Research Review, 43(2), pp. 150-165. DOI: 10.1108/MRR-04-2019-0151.

James, R. (2021). Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction among repatriates: repatriation adjustment as a mediator. International Journal of Management Practice, 14(6), 701-715. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMP.2021.118938.

Kudo, L. K., McPhail, R., & Vuk Despotovic, W. (2024). Retaining the repatriate by organisation in developing countries (in Africa): understanding the decision-making point (stay or leave) of the expatriate. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 46(2), 366-382. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2020-0466.

Kumar, S., Aslam, A., & Aslam, A. (2022). The effect of perceived support on repatriate knowledge transfer in MNCs: The mediating role of repatriate adjustment. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management, 17, 215-234. https://doi.org/10.28945/4979.

Latukha, M., Soyiri, J., Shagalkina, M. & Rysakova, L., (2019). From expatriation to global migration: The role of talent management practices in talent migration to Ghana. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 7(4), pp. 325-345. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2018-0062.

Lehtonen, M. J., Koveshnikov, A., & Wechtler, H. (2023). Expatriates’ embeddedness and host country withdrawal intention: A social exchange perspective. Management and Organization Review, 19(4), 655-684. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2022.48.

Liu, M. (2024). Exploring the impact of cultural re-adaptation on returnee talents in China: the case of returnee PhDs from the UK. http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/5327.

Lo, F. Y., & Nguyen, T. H. A. (2023). Cross-cultural adjustment and training on international expatriates’ performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 188, 122294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122294.

Minbaeva, D., Narula, R., Phene, A., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2025). Beyond global mobility: How human capital shapes the MNE in the 21st century. Journal of International Business Studies, 56(2), 136-150. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-024-00755-x.

Moonsup, J., & Pookcharoen, S. (2017). Reverse Culture Shock: Readjustment Problems Encountered by Thai Returnees after Returning from an AFS Exchange Program Abroad. Thammasat University. https://ethesisarchive.library.tu.ac.th/thesis/2017/TU_2017_5406040062_8893_8781.pdf.

Nag, M. B., & Malik, F. A. (2023). Repatriation Management and Competency Transfer in a Culturally Dynamic World. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-19-7350-5.

Pasmatzi, K. (2022). Theorising translation as a process of ‘cultural repatriation’ A promising merger of narrative theory and Bourdieu’s theory of cultural transfer. Target, 34(1), 37-66. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.20056.pas.

Peltokorpi, V., Froese, F. J., & Reiche, S. (2021). How and when do preparation and reintegration facilitate repatriate knowledge transfer. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2021, No. 1, p. 11308). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2021.56.

Read, R., & Fenge, L. A. (2019). What does Brexit mean for the UK social care workforce? Perspectives from the recruitment and retention frontline. Health & social care in the community, 27(3), 676-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12684.

Ribeiro, A. F. O., & Silva, I. S. (2025). Expatriate Workers: Impact of Change on Adaptation to the Destination Country. In Human Resource Management in a Disrupted World (pp. 309-330). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-89948-5_13.

Roberts, M., Muralidharan, E., & Cave, A. H. (2025). International experience, growth opportunities, and repatriate job satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 42(1), 74-91. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1760.

Shah, S.N.A. & Baber, Z.N., (2023). Talent management of repatriation is today’s challenge in the absence of unilateral repatriations support practices of the organization. Journal of Excellence in Management Sciences, 2(1), pp. 32-45. https://journals.smarcons.com/index.php/jems/article/view/94.

Sreeleakha, P., (2014). Managing culture shock and reverse culture shock of Indian citizenship employees. International Journal of Management Practice, 7(3), pp. 250-274. DOI:10.1504/IJMP.2014.063597.

Trinh, S., (2023). Challenges faced by the organizations in managing the repatriation: A case from IT sector. International Journal Of Business And Social Analytics, 2(1):1-11. DOI:10.26710/sbsee.v2i1.1178.

Valk, R. (2022). A squeezed lemon or an appetizing olive? Exploring expatriate and repatriate talent management. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 44(6), 1516-1537. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2021-0310.

Yaro, A. S., Maly, F., & Prazak, P. (2023). Outlier detection in time-series receive signal strength observation using Z-score method with S n scale estimator for indoor localization. Applied Sciences, 13(6), 3900. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063900.

Zavala-Barajas, S. L., Eltiti, S., & Crawford, N. (2022). Contributing Factors in the Successful Repatriation of Long-Term Adult Christian Missionaries. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 00916471221082056. https://doi.org/10.1177/00916471221082056.

Zhong, Y., Zhu, J. C., & Zhang, M. M. (2021). Expatriate management of emerging market multinational enterprises: A multiple case study approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(6), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060252.

Licensed

© 2025 Copyright by the Authors.

Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.

Article Contents Author Yazeed Alsuhaibany1, * 1College of Business-Al Khobar, Al Yamamah University, Saudi Arabia Article History: Received: 03 September,

Article Contents Author Muhammad Arslan Sarwar1, * Maria Malik2 1Department of Management Sciences, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan; 2COMSATS

Article Contents Author Tarig Eltayeb1, * 1College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Kuon Keong Lock1, * and Razali Yaakob1 1Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia,

Article Contents Author Shabir Ahmad1, * 1College of Business, Al Yamamah University, Al Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Ghanima Amin1, Simran1, * 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Sialkot, Sialkot 51310, Pakistan Article History: Received:

PDF

PDF