Article Contents

Genetic and Biotechnological Approaches for Mitigating Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture

⬇ Downloads: 57

1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Sialkot, Sialkot 51310, Pakistan

Received: 20 August, 2025

Accepted: 26 October, 2025

Revised: 22 October, 2025

Published: 17 November, 2025

Abstract:

Global agriculture is under serious threat from climate change resulting from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial activities. Climate change will exacerbate the impacts from droughts, flooding, salinity, and extreme temperatures, which impact food security and disrupt the ability of crops to grow and produce yields, especially in regions that are particularly susceptible to climate change. This study presents an extensive and innovative framework for integrating molecular innovations into sustainable agricultural practices. It merges genetic and biotechnological innovations to address climate change issues. This study, in several different contexts, critically examines advances in genome editing technologies, including CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs, as well as advancements in base and prime editing. The study highlights how molecular innovations may enhance crop stress resistance, nutrient uptake, and carbon sequestration. Bt cotton, drought-resistant maize, and salt-tolerant rice are successful applications of genetic engineering to address climate change. Furthermore, biotechnological innovations such as carbon sequestration techniques, bioenergy crops, and biofertilisers also help to establish sustainable food systems and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This review combines the areas of environmental biotechnology and molecular genetics to develop a new and different multidisciplinary approach for developing sustainable, climate-resilient agricultural practices.

Keywords: Climate change, CRISPR/Cas9, Bt cotton, crop productivity, genetically modified crops, drought resistance.

1. INTRODUCTION

A worldwide phenomenon based on human activity is climate change, which includes using fossil fuels, cutting down forests, and conducting industrial operations. Since the mid-20th century, human-generated greenhouse gas emissions have significantly increased, increasing Global temperature by approximately 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels [1]. This tendency alters weather patterns, intensifies heatwaves, causes erratic rainfall, and disrupts hydrological cycles. These changes pose enormous dangers to ecosystems, water resources, and human health, with far-reaching consequences for agriculture, a critical sector for food security and economic stability. Climate change poses a significant risk to agricultural and animal sectors, disrupting food delivery networks and livelihoods, particularly in underdeveloped regions [2]. Furthermore, climate change contributes significantly to resource degradation, resulting in challenges like soil erosion, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss.

Classic approaches for lessening the adverse effects of climate change on agriculture are conventional breeding, improved irrigation, crop rotation, and soil fertility management. These approaches have been generally practical but tend to have only a limited effect. Natural genetic diversity is often heavily relied on, and many of these approaches, although addressing the effects of stressors, cannot adapt to multiple stressors simultaneously [3, 4]. Additionally, the rapid pace of environmental change often outpaces the ability of many conventional programs to adapt. These challenges underscore the pressing need for novel genetic and biotechnological advances to develop high-yield, stress-tolerant crop types quickly. Recent biotechnology and molecular genetics innovations have yielded new climate change responses in agriculture. New methods such as CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs, as well as advanced approaches including base and prime editing, provide exceptional precision in managing plant genomes’ drought, high salinity, temperature fluctuation, and pest susceptibility [5, 6]. In addition, biotechnology has excellent potential to mitigate agriculture’s environmental impact through methods such as eco-friendly fuels, carbon sequestration, bioenergy, and biofertilisers.

Nevertheless, most of the reviewed literature tends to highlight specific crops or technologies rather than investigate the complementary use of genetic and biotechnological approaches towards climate-resilient, sustainable agricultural practices (Technological Advancements in the CRISPR Toolbox, 2024). To inform ways to mitigate climate change in agriculture, this article will therefore provide a coherent summary of genetic and biotechnological approaches. Moreover, the article illustrates that molecular advancements can complement biotechnological approaches to improve yield, reduce carbon emissions, and enhance sustainability. This review is novel in holistically combining genetic and biotechnological approaches while discussing their real, economic, and environmental consequences. Specific approaches include techniques for carbon sequestration, microbiome and biofertiliser applications, advanced gene editing techniques, and bioenergy approaches. This paper provides a comprehensive framework for developing climate-resilient and sustainable agricultural systems in an ever-changing climate. This review is unique in this respect from previous works.

1.1. Direct Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture

Environmental conditions alter agriculture and farming methods over time, connecting local farmers’ experience and resources with crop-specific agricultural practices that thrive in the current environment. Higher growing season temperatures significantly influence food security, farm profitability, and agricultural production [7]. At mid and high latitudes, agricultural productivity and adaptability are predicted to increase and move northward, particularly for cereals and cool-season seed crops [8, 9]. Crops commonly grown in Southern Europe, like maize, sunflowers, and soybeans, might become feasible further north and at higher elevations. Yields may increase by up to 30% by the 2050s, depending on the crop [9–11].

Higher temperatures might have an immediate negative impact in regions where crop tolerance levels are already close to their maximum, such as seasonally dry and tropical zones. This would result in increased heat stress on crops and increased water loss through evaporation. 28° C A temperature rise in mid-latitudes might improve wheat productivity by around 10%; however, in low-level latitudes, the same temperature increase could diminish yields by a similar percentage. Understanding the critical role of water in plant growth demonstrates the significant impact that different precipitation patterns have on agriculture. Since rain is used in more than 80% of agricultural practices, predictions about future precipitation fluctuations regularly influence the kind and amount of climate effects on crop productivity [12–14]. Predicting the effect of global warming on local rainfall is difficult due to complex interactions with atmospheric circulation patterns. However, forecasts indicate that high-latitude precipitation increases, particularly during the winter, while tropical and subtropical regions will decrease, with the IPCC expressing greater confidence in these projections.

1.2. Extreme Weather Events and Climate Variability

While modifications to the ongoing climate conditions will impact global food output and can demand continuing adaptations, fluctuations in annual weather patterns and severe climatic events pose the greatest threat to food security. Historically, many of the most dramatic losses in crop yield have been linked to extremely low precipitation levels [15, 16]. Even modest variations in average annual rainfall can affect productivity. A one-standard unit difference in precipitation throughout the growing season can result in a 10% change in yield, like millet in South Asia [17]. For example, found that the Productivity of Indian agriculture is primarily reliant on the unique temporal and geographical trends of monsoon rainfall [16]. In 2009 research, Asada and Matsumoto investigated the connection between different crop level output statistics, specifically for ‘kharif’ rice during the rainy season and precipitation from 1960 to 2000 [18]. Their findings demonstrated that different geographical locations have variable sensitivity to extreme precipitation occurrences.

Crop output in the upper Ganges basin is determined by the level of rainfall received during the shorter growing season, rendering it susceptible to drought. In contrast, the lower Ganges basin is prone to excessive rainfall, but the Brahmaputra basin is experiencing a significant influence of precipitation changes on yield, particularly during droughts. These relationships changed over time, in part because of changing precipitation patterns. Disparities between districts highlighted the significance of socio-economic factors and the use of irrigation systems.

During the summer of 2003, Europe saw an abnormally harsh weather phenomenon, with temperatures rising 6.8° C above average and precipitation shortfalls of up to 300 mm. The severe heat caused a remarkable 36% loss in corn crop productivity in Italy’s Po Valley [19]. Human-induced alterations in climate have increased the likelihood of such high summer temperatures in Europe by 50 percent [20].

1.3. Extreme Temperatures

Crop yields in European countries may have been influenced by rising climate variability since the mid-1980s, resulting in greater year-to-year changes in wheat production [21]. High temperatures can harm mid-latitude crops if they are not adapted. The former Soviet Union’s (USSR) unusually high summer average temperature in 1972 caused severe changes in world wheat food safety and markets [7]. Temperature extremes that occur during crucial development phases are significant. A brief period of extremely high temperatures (more than 32°C) during the flowering phase of some plants can significantly lower agricultural output [22]. In the near term, enzymes are disrupted due to high temperature changes in processes and gene expression. Longer term, these will affect carbon assimilation, yield, and growth level. Effects on yields due to high temperatures vary depending on the level of crop development. Plants experience warming episodes as independent occurrences, and threshold temperatures of 358°C around anthesis had substantially reduced yield consequences [23]. However, there were no signs of high temperatures significantly impacting growth and development during the vegetative stage. Reviews of the literature, Wilhite [22, 24], reveal that temperature thresholds are defined and substantially conserved between the species, notably for processes like anthesis and grain filling. Despite being planted in semi-arid settings with temperatures reaching 40.8°C, groundnut plants can have a significant drop in production if exposed to temperatures above 42.8°C post-flowering, for brief periods of time.

1.4. Droughts

Droughts are a primary concern for environmental campaigners, ecologists, hydrologists, meteorologists, geologists, and agricultural professionals. They occur in almost all climate areas, ranging from high to low rainfall levels, and are primarily associated with a decline in precipitation levels over a lengthy time, whether a season or a year.

Droughts are impacted by temperature, wind, humidity, and rainfall patterns, including timing, intensity, length, commencement, and termination. Unlike aridity, a permanent characteristic of climates in low-rainfall zones [25], droughts are only transitory. Heatwaves and droughts, stating that heatwaves typically last approximately a week, but droughts can endure for several months or even years. A heat wave and a drought together have serious socio-economic repercussions.

Droughts substantially impact surface and groundwater resources, resulting in decreased water availability, untreated water, crop failure, decreased range production, lower power generation, damaged riparian habitats and halted recreational activities. Droughts also impact water quality by altering hydrologic patterns, resulting in considerable changes in lake chemistry. Droughts interrupt the movement of nutrients, and sediment and biological material are released to surface waterways by runoff.

1.5. Heavy Rainfall and Flooding

Excessive water use also has an impact on food output. Flooding caused by heavy rains can ruin entire harvests across large areas, and excess water can cause soil waterlogging, anaerobic conditions, and stunted plant growth. Secondary impacts include postponed agricultural activity (Falloon & Betts, forthcoming). Farming equipment may not be suitable for saturated soil conditions. A link between severe August rainfall and poor grain quality, resulting in grain sprouting in the ear and fungal infections [26].

As the temperature rises, the proportion of total rainfall that falls during heavy rainfall events is anticipated to continue rising. A doubling of CO2 will result in more severe rainfall across Europe. According to the higher estimations, rainfall levels increase by more than 25% in several locations crucial for agriculture.

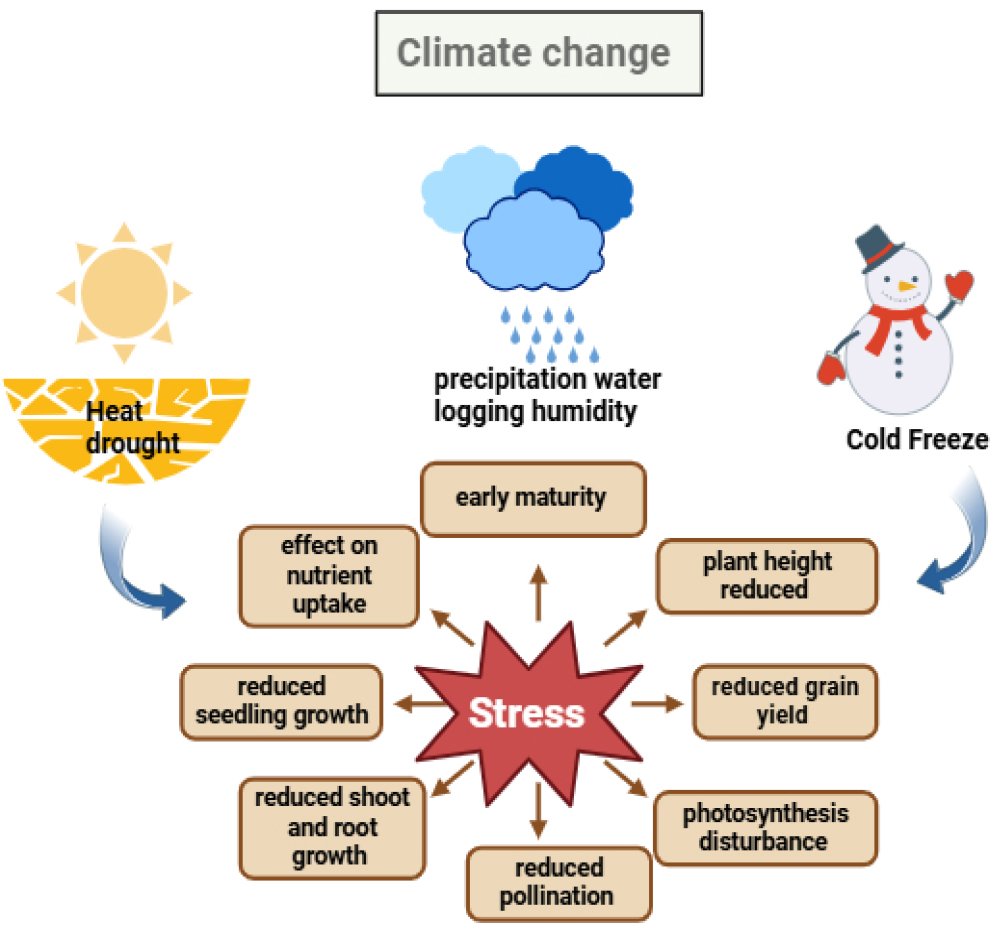

Fig. (1) shows how plant stress is caused by climate change elements such as heat, drought, excessive precipitation and cold freezes. The ensuing stress impairs vital physiological processes, leading to decreased crop output, growth, pollination and nutrient intake.

Fig. (1). Effect of climate change-induced stress on plant growth.

1.6. Overview of Biotechnology Role in Agriculture and Its Importance in Addressing Climate Change

1.6.1. Agricultural Biotechnology

Agricultural biotechnology refers to practical applications of living organisms or their subcellular elements in farming. Methods used include tissue culture, traditional breeding, molecular marker-assisted breeding and genetic alteration. Growing plant cells or tissues in specific nutritional solutions is known as tissue culture. Regrowing an entire plant from a single cell under ideal circumstances is a quick and essential method for producing healthy plants on a large scale [27]. Understanding breeding breakthroughs is critical for agriculture to increase yields and meet the demands of an increasing population while remaining within land and water resource limits. Since 1995, improved plant breeding technologies have resulted in a 21% rise in worldwide primary yield production, including maize, wheat, rice, and oilseed.

In contrast, acreage dedicated to these crops has increased only marginally by 2% [28]. Researchers can quickly and precisely identify plants with desirable features by identifying gene locations and potential functions, allowing for more exact execution of traditional breeding methods [29, 30]. Biotechnology enables the development of disease diagnostic kits aimed at the early detection of plant ailments in laboratory and field settings. These kits detect the genetic material (DNA) or proteins linked with pathogens or plants during infection. Combining old agricultural biotechnologies with contemporary biotechnology approaches produces superior results [27]. Recent agricultural biotechnology includes biotechnological methods for modifying hereditary material and combining cells across breeding lines. A primary example is genetic engineering using transgenic technology involving gene insertion or deletion. Genetic modification or transformation is the process of artificially manipulating genetic material, such as isolating genes, cutting certain regions using specialised enzymes and transferring selected DNA fragments into the target organism’s cells. A common strategy in genetic engineering is to use the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a carrier to transfer the desired genetic feature [31]. A newer technique known as ballistic impregnation involves attaching DNA to a small gold or tungsten particle and propelling it into plant material [32]. Over the last two decades, significant advances have been made in altering genes from varied and exotic origins. These genes are subsequently integrated into microorganisms and crops, providing resistance to pests and diseases and lenience to weedkillers, drought, soil salinity and aluminium harmfulness. Furthermore, this process seeks to improve post-harvest excellence, increase nutrient uptake and nutritional value, increase photosynthetic frequency, increase sugar and starch making, improve the efficacy of biocontrol agents, advance consideration of gene functions and metabolic pathways and facilitate the synthesis of drugs and vaccines within crops [30, 33].

1.7. Biotechnology for Climate Change Qualification

1.7.1. Greenhouse Gas Reduction

Agricultural activities like deforestation, the use of synthetic fertilisers, and overgrazing are responsible for around 25% of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, CH4, and N2) [28]. Implementing green biotechnology activities may solve falling greenhouse gas emissions and opposing climate change. These measures could encourage farmers to use more sustainable energy sources, engage in carbon sequestration practices and reduce their fertiliser dependency [28].

1.8. Use of Environmentally Approachable Fuels

Specifying the considerable impact of climate change on agricultural production and the crucial role of agricultural practices in global warming, agricultural techniques must play an important part in the competition compared to climate change. Using biofuels derived from outdated and genetically modified crops such as sugarcane, soybean, rapeseed and jatropha can significantly reduce the negative impact of CO2 emissions from the transportation range [28, 34]. Cultivating non-edible oilseed plants can reduce reliance on fossil fuels by purifying the atmosphere and producing biodiesel [35–37].

1.9. Less Fuel Consumption

Organic farming reduces fuel consumption by composting and mulching, resulting in less weed and pesticide spraying due to reduced ploughing [38]. Reducing irrigation would cut fuel usage and CO2 emissions. Modern biotechnology, including genetically modified organisms GMOs, reduces the need for spraying and tillage, resulting in lower fuel usage. Insect-resistant GM crops can cut fuel use and CO2 emissions by lowering insecticide levels. In 2005, biotechnology reduced fuel use and saved almost 962 million kg of CO2 emissions. Similarly, reducing or no tillage practices resulted in CO2 emissions reductions of 40.43 kg/ha and 89.44 kg/ha, respectively, owing to lower fuel consumption [39].

1.10. Biofertilisers

Modern biotechnology has boosted the nitrogen-fixing capacities of Rhizobium strains through mutation and genetic manipulation [40]. Biotechnological advancements, such as inducing nodular structures on cereal crop roots like rice and wheat, point to a hopeful future in which non-leguminous plants could potentially fix nitrogen in the earth [41–44].

Growing genetically modified (GM) crops can improve nitrogen utilisation. One such example is GM canola, which is nitrogen-efficient, specifically lowering the quantity of nitrogen fertiliser that goes into the troposphere, soil, and water systems. It also benefits farmers’ economics by increasing profitability [28]. Adjusting loam nitrogen levels to fit yield requirements can decrease N2O emissions while protecting water quality. Furthermore, changing animal diets and managing manure can reduce methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from animal agriculture [45].

1.11. Biotechnology for Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

Agricultural biotechnology can improve crop output by developing lines resilient to biotic stressors such as pests, fungi, bacteria, and viruses. The Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) DNA segment is transferred to corn, cotton, and soybeans to provide insect and pest resistance, while remaining nonviolent for humans and the environment. Genetically modified crops are effectively used for integrated pest management. The herbicide tolerance attribute has been introduced into corn, soybeans, and canola. Genetically modified crops such as potatoes and cassava are being developed to resist biotic stressors, with some already commercialised [46].

Abiotic stress, like biotic stress, is a critical concern that must be addressed to ensure sustainable growth. Abiotic stresses include factors like salt, drought, severe temperatures, and oxidative stress, which have a direct impact on farming and the natural atmosphere. Plant biotechnology, together with social standing, is a significant technique for improving crop abiotic stress tolerance. This strategy involves selecting and cultivating drought-resistant crops that can thrive in difficult circumstances on borderline soils.

Molecular breeding strategies for abiotic stress resistance rely on upregulating genes related to stress response. Researchers have successfully created genetically modified varieties to tolerate drought, salt, and extreme temperatures, including Arabidopsis, tobacco, maize, wheat, filament, soya, pearl millet, tomato, rice and brassica. This progress is attributed to several experts, including [47–51]. The sequencing of genomes in many microorganisms and plants ushers in a new age, allowing us to rapidly change stress tolerance genes and perhaps influence climate dynamics.

1.12. Carbon Sequestration

Carbon can be extracted directly from the environment or through industrial and combustion processes, usually CO2. Techniques such as soil carbon sequestration provide a way to combat rising amounts of atmospheric CO2. Conservation strategies reduce soil erosion, help capture soil carbon, and improve methane (CH4) absorption [45, 52]. The growth of genetically altered yields such as Roundup ReadyTM (herbicide-resistant) led to the requisitioning of 63,859 million tons of CO2 [53–55]. The need for cultivation or ploughing can be concentrated using genetically engineered harvests.

Genetic engineering enables us to modify plants to absorb more CO2 from the environment and adapt to oxygen. Incorporating bacteria into the soil helps to improve its fertility. Modern environmental biotechnology has proven increasingly important in tackling these concerns within this paradigm.

1.13. Reduced Use of Fertilisers

The use of agricultural pesticides pollutes the environment with harmful contaminants, disrupting biogeochemical processes. Greenhouse gas emissions from soil, particularly N2O, are predominantly caused by the use of inorganic nitrogen-based fertilisers like ammonium sulphate, ammonium chloride, and ammonium phosphates. Introducing biotechnology-derived fertilisers presents a possible alternative to offset the negative effects of traditional fertilisers.

Biotechnology provides an advantage in reducing the need for chemical fertiliser. Genetic engineering boosted the nitrogen-fixing ability of Rhizobium inoculants [40]. Inducing nodular formations on cereal crop roots, like rice and wheat, has the probable ability to enable non-leguminous plants to fix nitrogen [41–44].

1.14. Climate Change Adaptation for Bioenergy Crops

Adaptation in bioenergy crops involves strengthening crop production systems against climate-induced challenges such as shifting temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather [56–58]. The significance of climate adaptation in the bioenergy crops situation stems from its ability to safeguard agricultural productivity, food safety and ecological services in the face of fluctuating weather circumstances. Given bioenergy crops’ dual role in climate change mitigation and renewable energy ambitions, guaranteeing their ability to tolerate climate-related hazards is critical to maintaining a stable and reliable energy source while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, cultivating bioenergy crops provides other benefits such as carbon capture and soil preservation, highlighting the importance of integrating adaptation efforts to achieve larger environmental and socio-economic goals [59, 60].

1.15. Biotechnology for Improved Crop Per Unit Area of Land

To meet the increasing global mandate aimed at food crops, there are two main strategies: expanding the cultivated land area or enhancing productivity on farmland [61]. Incorporating organic residues as plant nutrients, implementing effective agronomic practices like landscape management and crop rotation, utilising traditional methods for pest control without chemicals, and some conventional approaches [62]. Additionally, biotechnology and advanced breeding techniques can enable agriculture to boost yields and cater to the needs of a growing population while facing constraints in land and water resources [28].

1.16. Agroecology and Agroforestry

The effects of worldwide climate alteration on temperature and rainfall patterns substantially threaten tropical agriculture. Implementing agroecological and agroforest running strategies, like using gloom in crop classifications, can help ease the negative consequences of harsh weather. These measures attempt to lower rural farmers’ economic and ecological vulnerability, improving their ability to survive extreme climate events.

Fungal biotechnology, also known as mycobiotechnology, contributes to the rising movement of living organisms to address eco-friendly challenges and restore damaged systems. Mycoforestry and myco renewal sciences are part of an emerging field of study and practical application aimed at restoring broken forest ecosystems [63].

Mycorestoration aims to use fungi to repair or recover environmentally affected ecosystems. Endo- and ectomycorrhizal symbiotic fungi, in combination with actinomycetes, have been shown to be useful as inocula in the restoration of impoverished forestry [43]. Hence, the use of both mycorrhizal fungi and actinorhizal bacteria technologies aims to boost soil fertility and enhance plant water absorption. Additionally, afforestation could indirectly enhance agricultural output and food security by fostering microclimates that improve precipitation availability.

1.17. Genes Regulate Plant Physiological and Biochemical Actions Under Salt Stress

Genes are crucial in mitigating plants’ abiotic stresses by aiding their growth, nutrient absorption, and internal transportation. Specific genes like SKC1, MAPK and CDPK pathways, and SOS pathways, CHS and PAL, actively regulate plant retorts to salt stress. Notably, the genes SOS1 and NHX1 convert the Na+/H+ antiporter, with SOS1 localised on the plant’s plasma membrane. SOS1 gene function regulates Na+ transport from the plant’s roots to its leaves. Additionally, the TaNHX gene contributes to enhanced plant salt stress tolerance by limiting Na+ uptake and its translocation to the plant leaves in tomato and rice. NHX protein performance has been extensively studied in crops like tomatoes, rice and cotton.

However, AtNHX1 gene overexpression in tomatoes increased K+ retention in cells under sophisticated salt stress [64]. Similarly, in transgenic tobacco, the TNHXS1-IRES-TVP1 bicistronic transcriptional element produced increased K+ accumulation and decreased Na+ concentration in leaf tissue [65]. Increased antioxidant activity, such as SOD, POD, and CAT, lowers ROS generation and cellular harm in vegetation.

1.18. Integrated Methods for Growing Plant Yield Under Drought Stress

Drought presents a considerable obstacle to global agricultural productivity. While the outcome of climate alteration on drought harshness is uncertain [66], frequency and unpredictability of these events are critical factors in the following modelling estimates [67, 68]. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of plant responses to drought presents a challenge because of variations in (i) the characteristics regulating plant water levels in response to rapidly shifting soil moisture and evaporation demands, (ii) how plants react to alterations in water levels, their genetic diversity, and variances among types (e.g., cereals versus legumes), and (iii) the interaction of additional factors like the timing then length, growth of the crop.

Today, there is a rising recognition of many drought circumstances that exist in different locations worldwide, both now and in the future [69–71]. This includes noticing the diversity even within a single field across multiple years. Matching plant phenology and features with the most likely circumstances in each environment is critical. This stresses the need to use probabilistic methods to improve drought resistance. Such methods combine crop modelling with genomic forecasting to identify the most favourable alleles or features for certain drought conditions at specific periods and locations [71, 72].

1.19. Physiological and Molecular Basis of Drought Tolerance in Plants

Officially accepted words for plant water status follow Hsiao’s (1973) classification of ‘hydrated’, ‘moderate stress’, ‘mild stress’, ‘severe stress’, and ‘dripping’, which is founded on the extent and duration of water deprivation. In this research, [73] distinguishes between dryness and desiccation tolerances, which is important for phenotyping and understanding recovery and existence processes [74].

Four decades of investigation on the benefits of osmotic alteration in maintaining turgor during droughts in specific habitats [72]. The discussion focuses on genetic diversity modification and breeding strategies for improving crop resilience in water-stressed environments. Notable examples are drought-resistant wheat types that activate the OR gene to regulate osmotic balance in leaves and pollen.

A crop cover comprises discrete plants that share genetics but have unique traits. Borrás and [75] study the role of inter-plant variability on plant growth and ear growth, focusing on current genetic advances. This development is determined by (i) the plants’ ability to attain significant yields at dense plant populations while maintaining uniformity among them, and (ii) the rate of silk synthesis in relation to ear or plant biomass.

Understanding the message and tone of the original statement is essential. The simultaneous occurrence of drought and heat episodes needs a unified tolerance approach, despite the separate genetic underpinnings for high temperatures and drought [76]. After comparing features with comparative benefits, these researchers concluded that maintaining adequate plant water levels is critical for surviving both stressors. This is accomplished by making precise modifications to gas exchange and plant hydraulic conductance and utilising adaptive root system responses and classic heat-resistant processes. Improving many plant plasticity features simultaneously is a problematic mission that can be accomplished by combining phenomics, quantitative genetics, QTL cloning, and genome expurgation approaches [77].

1.20. Advances of Genetic Engineering

To address the growing food requirements of the expanding global population, simply incorporating a single gene for a specific trait is inadequate. Instead, there is a rising necessity to cultivate crops possessing intricate characteristics like resilience to stress, efficient utilisation of nutrients, and combinations of various traits [78]. Conventional breeding has proven effective in trait stacking; however, stacking only a few independent loci is feasible, making it a time-consuming process that presents fresh hurdles for researchers [79]. The advanced methods for genome excision can transform agricultural research by surmounting the constraints of conventional breeding and RNA interference methods. Utilising engineered nucleases like zinc-finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases and CRISPR/Cas9, this technology can produce enhanced crops that are practically the same as naturally occurring mutant varieties.

Genetically modified crops aim to boost food’s nutritional value, increase yield, enhance resistance to environmental factors, and safeguard plants from pests. Through genetic modification, plant breeders can innovate plant traits effectively, potentially addressing critical issues in up-to-date agriculture. Agrobacterium as a biological vector and direct gene transfer techniques facilitate gene transfer into plants. Agrobacterium-based methods are more efficient than other gene transfer approaches; however, they may not be universally applicable across all plant species [80]. Therefore, specific individuals have resorted to utilising genetically modified crops to address the requirements of a shifting global environment.

1.21. GMO Crops for Climate Adaptation

Genetically engineered (GE) crops are becoming more acknowledged as a viable answer to adjusting agriculture to the difficulties presented by climate change.

1.22. Bt Cotton

Cotton is regarded as a single crop most impacted by environmental factors, climate situations, and planting periods compared to wheat and rice [81]. The timing for planting varies based on climate, the type of plant, and the agricultural environment (whether rainfed or irrigated), which significantly influences when crops are sown. Analysing crop yield and quality involves assessing how plant varieties interact with the planting date [82]. Bt cotton, engineered to resist lepidoptera pests such as the American and pink bollworm, may lower pesticide usage and boost yield in specific agroecological settings. This outcome is influenced by a combination of local/global economic factors, genetic variations in Bt cotton lines, and the ability to prevent crop loss in elevated temperature and rainfed environments compared to conventional non-Bt cotton [83 ,84]. Bt cotton, a significant genetically modified crop, was first launched by Monsanto in the United States in 1995. This variety of cotton is genetically modified to contain a gene sourced from a soil bacterium, which acts by attaching to the DNA of the bollworm pest and causing its demise upon consumption of the cotton leaf or bud [85]. Having gained approval in China in 1997 and established a joint undertaking with the Indian seed company Mahyco in 2002, this crop had expanded to 15 nations by 2019, with 13 developing countries [86]. Bt cotton has rapidly expanded to encompass 70% of the worldwide cotton cultivation, spanning approximately 35 million hectares, with a significant 50% share located primarily in India within a little more than 20 years [87]. Supporters contend Bt cotton exhibits enhanced pest management capabilities amidst changing climatic conditions.

Nevertheless, advancements in one aspect may be counterbalanced by reliance on alternative resources. For instance, the initial shift to Bt cotton has decreased pesticide application compared to non-Bt varieties. Yet, observations over 15–20 years in regions like China and India indicate a concerning trend as elevated temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns lead to the resurgence of secondary pests and Bt-resistant bollworms. This scenario necessitates heightened fertiliser and pesticide inputs to counteract reduced yields [88–90].

1.23. Salt-Tolerant Rice

The progress in creating genetically modified (GM) rice with improved resistance to salt is a notable breakthrough in agricultural biotechnology focused on tackling the difficulties brought about by climate change. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is the primary diet for more than 3.5 billion people globally, predominantly in Asia and Africa. By 2050, it is predicted that there will be 9.6 billion individuals worldwide. Therefore, it is imperative to improve rice cultivation to satisfy the increasing worldwide food requirements [91]. Numerous studies widely recognise salinity stress as a prevalent abiotic stress affecting rice, hindering crop advancement, development, and overall yield. Over 1000 million hectares of land have been approximated to be salty or sodic, with approximately 25% to 30% of wet regions (around 70 million hectares) experiencing salt-induced impacts, rendering them practically unproductive commercially [92]. Under salt-stressed conditions, plants’ responses to salinity stress are perceived as mechanisms to enhance rice grain yield. The literature shows salt tolerance as a multifaceted measurable characteristic influenced by numerous gene exchanges [93]. Rice plants are highly vulnerable to salt pressures, especially during the initial phases of growth [94] and reproductive stages [95], leading to significant grain yield reduction. Enhancing the salt tolerance of rice to increase productivity can be achieved through various methods. These approaches encompass utilising marker-assisted breeding to incorporate QTLs linked to salt tolerance, manipulating the appearance of genes in control for salt resistance to produce proteins and metabolites crucial for enhancing salt tolerance, and applying targeted protectants to activate the plant’s natural tolerance mechanisms, despite the availability of numerous comprehensive reviews on various facets of rice’s salinity [96, 97]. Extensive research suggests that understanding rice’s response to salinity stress requires analysing four domains: physiological responses, genetic modifications, genome changes, and molecular pathways. Sustainable initiatives to enhance rice growth and yield under salinity stress are crucial to meet the demands for this crop [98]. Various methods have been employed thus far in the creation of salt-resistant rice. Historically, the focus has been on water and soil management techniques and breeding strategies to achieve tolerance to salinity [99]. Using the latest research tools, such as microarray imaging, sequencing and recombinant DNA technology, has advanced information in rice salt stress biology and helped create novel approaches for maintaining salinity stress variation in rice [100]. An integrated strategy that combines biotechnology and molecular marker methods with traditional refinement methods is deemed especially appropriate for enhancing the salt tolerance of rice [99]. Five primary methods, comprising breeding, marker-assisted selection (MAS), externally administering plant growth regulators, genome editing, and genetic engineering, remain employed to enhance salt stress tolerance.

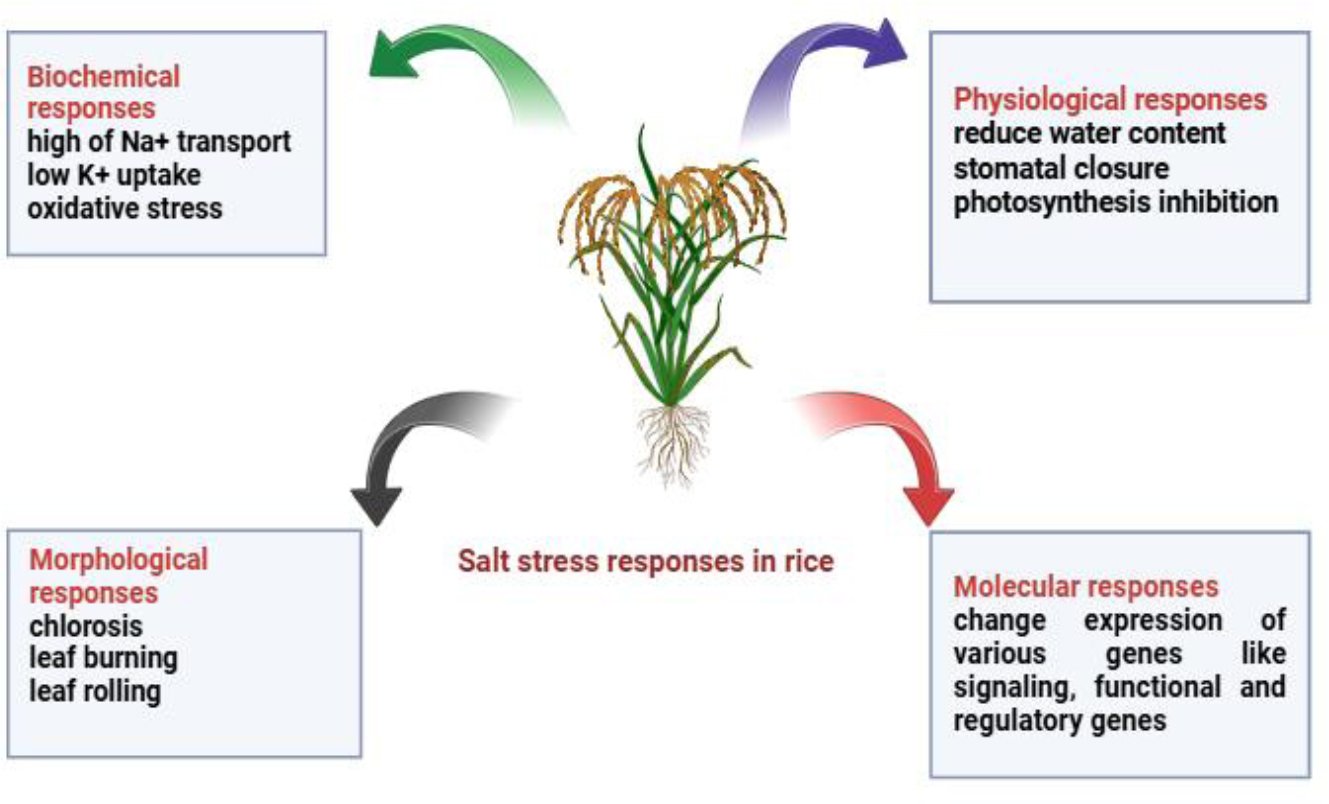

The main plant reactions to salt stress in rice are depicted in Fig. (2). Rice is impacted by salt stress in several ways: In rice, morphological, physiological, biochemical and molecular reactions are triggered by salt stress. These include decreased photosynthesis, ion imbalance, damaged leaves and altered gene expression. When combined, these reactions aid in the plant’s capability to resist salinity.

Fig. (2). Salt stress responses in rice.

1.24. Resistant Maize

The effect of climate change on economies varies, contingent upon the economic traits of individual countries. Climate change poses significant risks to regions already susceptible to food insecurity and malnutrition [101], where their economic system’s backbone is agriculture [102]. Climate change is exacerbating droughts and heat waves, prolonging their impact and making access to water supplies increasingly challenging. These conditions create hardships for crops to thrive in extreme situations induced by water scarcity. Maize, known for its tall and broad leaves, experiences leaf curling and inhibited growth when faced with a severe drought during its seedling or growth stages [103]. Before and after flowering, insufficiency of water significantly impacts maize yield. Hence, sufficient water provision is essential during this phase. The absence of moisture leads to drought stress in maize, impacting stages such as early vegetative growth, seedling emergence, photosynthesis, fertilisation, reproductive growth, seed development, and overall yield [104].

1.25. Techniques Used in Genetic Modification to Enhance Crop Resilience to Climate-Related Stressors

1.25.1. CRISPR

CRISPR/Cas system stands out as an up-and-coming technique for gene editing due to its accessibility, high efficiency, and simplicity in testing multiple single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for each gene. Moreover, it offers the unique ability to simultaneously introduce multiple double-strand breaks, edit methylated DNA regions crucial for targeting regulatory regions, and demonstrate greater efficacy in mutating plant genomes than previous systems like ZFNs and TALENs. Detailed discussions in recent reviews delve into the principles, advantages, mutation variations and diverse features of its application in plants, including genome stability post-editing, inheritance of modifications, frequency of erroneous changes, methods for acquiring non-transgenic modified plants, and the legal considerations surrounding the practical use of recently developed agriculturally beneficial plant forms [105–107]. The practical validation of the CRISPR/Cas system has been effectively demonstrated in 15 different yields, encompassing cereals like maize, wheat, rice and barley, as well as vegetables like tomato, cabbage and cucumber, along with fruits including apple and grape, citrus plants like orange, grapefruit, potato, watermelon, flax, and soybean. Across these crops, a total of 145 target genes were modified. To illustrate, in rice, three grain size regulators – GW2, GW5, and TGW6 – were instantaneously disabled using CRISPR/Cas technology. Consequently, a significant enhancement in grain length was achieved through the pyramiding of these three knocked-out genes, surpassing the effects of targeting a smaller gene subset [108]. By knocking out three and two homologous copies of the GASR7 gene, which acts as a negative regulator of grain mass, we could correspondingly enhance the grain mass of hexaploid and tetraploid wheat [109]. The grain weight and yield enhancement necessitate resistance to lodging, a trait conferred by plant dwarfness and stem robustness. Notably, disrupting the DEP1 gene in rice and wheat reduced plant height [109, 110]. To implement the CRISPR cleavage technique effectively, you need to have a concise artificial gRNA sequence consisting of 20 nucleotides that can attach to the desired DNA and the Cas9 nuclease enzyme capable of cutting 3–4 bases post the protospacer adjacent motif [111]. Cas9 nuclease encompasses the RuvC-like domains and the HNH domain, each of which is in control of cleaving a single DNA strand. Since the inception of CRISPR cleavage techniques, its application in editing plant and animal genomes has been extensive. The implementation of a CRISPR project includes basic steps: finding PAM sequence in target gene, synthesising a single guide RNA (sgRNA), cloning sgRNA into an appropriate binary vector, incorporating into cell lines, and conducting subsequent screening, validating edited lines is a crucial step in CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing (CMGE), enabling even modest laboratories equipped with basic plant transformation setups to undertake projects for genome editing. The widespread adoption of CRISPR/Cas9 techniques over the past five years for editing plant genomes surpasses that of ZFNs/TALENs, highlighting its user-friendly nature.

Nevertheless, while CRISPR expertise has been magnificently functional in model species like Arabidopsis, tobacco, and rice, only a few crop species have been explored in plants [112]. New breeding methods enable scientists to accurately and swiftly introduce wanted traits linked to outdated breeding. The CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique significantly advances this field. In the future, using genome editing tools to improve crops for better yields, enhanced nutritional value, and increased resistance to diseases will be key areas of attention. Concluded in the past five years, this technology has been actively used in various plants to study functions, address both biotic and abiotic stress, and enhance additional vital agricultural characteristics. While various improvements have increased the precision of this technology, much of the research is still in early stages and requires further refinement. However, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is expected to become increasingly popular and essential for creating ‘suitably edited’ plants, helping achieve the goal [113].

1.25.2. TALENS

The TALEN (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nuclease), recognised for its precision in genome editing, has been widely used for several years [114]. TALENs are engineered by fusing the FokI cleavage domain with TALE protein DNA-binding domains. TALEs consist of repetitive sequences of 34 amino acids, allowing for the targeted modification of a single base pair [115]. Similar to Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), TALENs introduce specific kinds of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, initiating the cellular pathways responsible for DNA repair and modification [116]. The TALEN system consists of proteins with a central domain responsible for DNA binding and a nuclear localisation sequence [117]. In 2007, researchers noted for the first time that these proteins can bind to DNA. Notably, the DNA-binding region features a sequence of 34 amino acids that repeats, with each repetition recognising a single nucleotide in the marked DNA. In contrast, each repeated sequence of ZFNs interacts with three nucleotides within the target DNA [118].

Traditional genome-editing tools, including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), create double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at sites of interest in the target DNA. After the DSBs are created, they are repaired in one of two ways: homology-directed repair (HDR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). These traditional methods have been restricted because of off-target effects, limited targeting potential, and protein engineering difficulties [119]. Conversely, the CRISPR/Cas9 system utilises a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to find targets, allowing for a more efficient and programmable genome editing method in plants and other organisms (Table 1) [120].

Table 1. Comparison of three main genome editing technologies: CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs.

| PROPERTY | ZFN | TALENS | CRISPR |

| Construction | Protein engineering for single target. | Protein engineering for single target. | 20-nucleotide sequence of sgRNA. |

| Delivery | Two ZFNs around the target sequence are required. | Two TALENs around the target sequence are required. | sgRNA complementary to the target sequence with Cas9. |

| Affordability | Time consuming and resource intensive. | Time consuming but affordable | Highly affordable |

| Mutation rate (%) | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| Off target effects | High | Low | Variable |

| Application | Human cells, zebrafish, mice and tobacco. | Human cells, cow, mice and water fleas. | Human cells, cereals, drosophila and vegetables. |

Although CRISPR/Cas9 has proven to be a powerful genome-engineering tool, it still operates at the level of DSBs, which can lead to unwanted insertions or deletions. Recently, newer methods have been developed that have more precision and experience less DNA damage than CRISPR/Cas9, including base editors (BEs) and prime editors (PEs). BEs translate edits from one nucleotide to another directly (e.g., C to T or A to G), are less error-prone, and offer more efficiency than traditional genome editing methods as BEs avoid the need for donor templates during the editing process and operate on the principle of converting one base to another without the need for DSBs [119]. PEs, in contrast, combine a Cas9 nickase with a reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to offer enhanced precision in making small insertions and deletions, as well as other categories of base substitutions [120, 121]. New research on plants reflects substantial progress toward integrating these technologies to improve crop traits. For example, the ability to speed up genetic editing in crops, including wheat, maize, and rice, has been improved through advanced variations of reverse transcriptase, selective temperature control, PEGRNA design, and other methods [122]. These advances provide advancements to manipulate complex traits critical to climate-resilient agriculture, including disease resistance, drought resilience, and reduction of nutrient inputs. Despite many advancements in editing genomes happening quickly, other ethical, biosafety, and regulatory challenges arise. Some countries differentiate between gene-edited crops, free of any foreign DNA, and traditional GMO crops, while others equate the laws for both [123]. The Ethical and Legal Implications Review [124] describes ethical challenges, including equity of access to gene editing benefits, public acceptability, and potential ecological impacts. Biosafety evaluations (International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023) suggest the importance of open risk assessment, off-target analysis, and responsible utilisation of advancements for agricultural biotechnology [125].

1.26. Benefits of Biotechnological Innovations

1.26.1. Economic Advantage of Engineered Crops in Sustainable Agricultural Practices

Despite the extensive usage of GM crops, the choice of blends of crops and traits remains significantly limited. Few initial technologies have reached commercialisation. The principal technology, herbicide tolerance (HT) in soybeans, accounted for 53% of the worldwide GM crop area in 2008. HT soybeans are mostly grown in Argentina, Brazil, the United States, and additional South American countries, accounting for 70% of global soybean yield.

In 2008, GM maize accounted for 30% of worldwide GM acreage and 24% of maizethe crop, making it the second most extensively grown crop. This genetically modified maize integrates insect resistance and herbicide tolerance through independent and stacked methods. The insect resistance feature depends on specific genes derived from the earth bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), which target pests like the European corn borer, maize rootworm, and different stemborers [126]. While Bt maize is mostly grown in North and South America, it is also grown extensively in the Philippines and South Africa.

Canola and Cotton are two GM crops that have significant market share. Bt cotton, resistant to bollworms and budworms, is very beneficial in underdeveloped countries. By 2008, India dominated in Bt cotton growing with 7.6 million hectares, tracked by China with 3.8 million hectares. Argentina, South Africa, Mexico, and others have adopted this technique. The United States uses Bt and HT cotton, which frequently incorporate stacked genes. Historically, HT canola thrived primarily in United States and Canada. Additional genetically modified crops, such as HT alfalfa, sugarbeet, and virus-resistant papaya and squash, have received permission in certain countries, but on a limited scale so far.

1.26.2. Genetically Modified Cotton and Rice

China is emerging as a global leader in genetically modified crops and technologies, with GM cotton and rice as significant examples. The introduction of Bt gene into chief cotton cultivars via novel Chinese pollen tube pathway represented a significant step forward [127]. Notably, Biotechnology Research Institute (BRI) of CAAS contributed substantially to plant disease resistance by creating fungal disease-resistant cotton. This was accomplished by adding glucanase, glucoxidase, and chitinase genes into important cotton cultivars. The approval for the environmental discharge of transgenic cotton. In 1997 and 1998, genetically engineered hybrid and traditional Bt rice cultivars that resist rice stem borer also leaf roller were permitted for environmental release [115]. Since 1997, genetic alterations have been created and permitted for release into the environment, including the Xa21, Xa7, and CpTi genes in rice to resist bacterial blight or rice blast. There has been substantial progress in cultivation of transgenic rice plants with increased drought and salt resistance. Field trials for transgenic rice with drought and salinity resistance began in 1998. Commercialisation of numerous genetically modified rice strains is theoretically viable. Nonetheless, the production and marketing of genetically modified rice are awaiting permission due to legislators’ concerns about food safety, rice trade, and the possible consequences for commercialising other genetically modified crops like soybean, wheat and maize.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Integrating multi-omics technologies, including proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics and genomes, is expected to greatly expand the part of biotechnology in farming. By making it easier to recognise and modify important genes associated with climate resilience, these tools will offer a greater understanding of plants’ complex stress comeback pathways. With a focus on modifying genetically modified crops to address the difficulties farmers face in particular agro-ecological zones, such as regions vulnerable to drought or salinity, this improved knowledge will enable researchers to create climate-resilient crop types specific to a given location. Furthermore, improvements in CRISPR/Cas genome editing will allow combining several desired features into a single crop variety, such as tolerance to pests, diseases, salinity and drought. This invention can greatly raise resilience and productivity, enabling crops to more effectively endure the effects of environmental stressors such as climate change. The biotechnological development of sustainable agricultural inputs, such as biofertilisers, biopesticides and bacteria that promote plant growth, should also be a focus of future breakthroughs. By lowering dependency on dangerous agrochemicals, these substitutes can promote more sustainable farming methods and enhance soil health. Policy frameworks must be strengthened in addition to technological improvements to enable the ethical application of biotechnology in agriculture. Promoting public acceptance of biotechnology will need to increase knowledge of its advantages and safety, particularly in developing nations where its effects can be revolutionary. Strong biosafety laws guarantee that biotechnology-based solutions are applied sensibly, mitigating possible hazards and optimising advantages for environmental health, food security and socio-economic advancement.

In conclusion, biotechnology in agriculture has a bright future ahead of it. Biotechnology can play a key role in developing resilient food systems that can adapt to challenges faced by climate change by utilising multi-omics techniques, customising crop varieties to local conditions, stacking advantageous features, and encouraging sustainable agricultural inputs. These developments have the potential to offer a more secure and supportable agricultural future with the right regulations and public involvement.

CONCLUSION

Increased temperatures, extended drought, salinity, and unstable rainfall will dramatically impact agricultural production. Creative alternatives will be required in addition to traditional agricultural practices. This review offers a new multi-faceted approach incorporating genetic and biotechnological innovations to generate crops with increased environmental resilience and durability without sacrificing environmental sustainability. Advanced gene-editing alternatives, including CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs, can develop actionable changes in stress-related genes for improving the resilience of plants, increasing productivity and efficiencies of resource use. Furthermore, biotechnological approaches, such as carbon sequestration, nitrogen-use efficient crops, and biofertilisers, further mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on chemical fertilisers. Biotechnology has demonstrated a pathway to varied successful outcomes in agriculture with commercially available crops, including Bt cotton, drought resistant maize and salt tolerant rice. The analysis provides a novel conceptual framework for sustainable crop development, which we hope will lead to food security and climate mitigation. This is achieved by integrating ecological biotechnology and molecular innovations. Fair access to biotechnological approaches, conducive regulatory frameworks, and ethical considerations must be addressed to achieve the maximum benefits of crop biotechnology. In conclusion, pairing genetic and biotechnological approaches opens the possibilities for resilient, sustainable, and climate-smart agricultural practices.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

Simran has contributed to data collection, data analysis and interpretation and writing of paper. G.A. has contributed to study concept/design, data collection and writing.

FINDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared None.

REFERENCES

[1] Glikson AY. An anthropogenic catastrophe. In: The trials of Gaia: Milestones in the evolution of Earth with reference to the Anthropocene. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23709-6_9.

[2] Godde CM, Mason-D’Croz D, Mayberry DE, Thornton PK, Herrero M. Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain: A review of the evidence. Glob Food Secure. 2021; 28:100488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100488.

[3] Liu Y. et al. CRISPR/Cas gene editing improves abiotic stress tolerance of crops. Genome Editing, 2022; 5:987817. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgeed.2022.987817.

[4] Afroz T. et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing for abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023; 14:1157678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1157678.

[5] Shelake RM. et al. Engineering drought and salinity tolerance traits in crops through CRISPR-mediated genome editing: targets, tools, challenges and perspectives. Plant Communications, 2022; 3:100417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100417.

[6] IPCC (2022) Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner DC, Roberts ES, Poloczanska K, Mintenbeck M. Tignor A, Alegría M, Craig S, Langsdorf S, Löschke V, Möller A. Okem (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001.

[7] Battisti DS, Naylor RL. Historical warnings of future food insecurity with unprecedented seasonal heat. Science.2009; 323:240-4. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164363.

[8] Tuck G, Glendining MJ, Smith P, House JI, Wattenbach M. The potential distribution of bio-energy crops in Europe under present and future climate. Biomass Bioenergy. 2006; 30:183-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.11.019.

[9] Olesen JE, Bindi M, Trnka M, Kersebaum KC, Skjelvåg AO, Seguin B, et al. Uncertainties in projected impacts of climate change on European agriculture and terrestrial ecosystems based on scenarios from regional climate models. Clim Change, 2007; 81:123-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9216-1.

[10] Richter GM, Semenov MA. Modelling impacts of climate change on wheat yields in England and Wales: assessing drought risks. Agric Syst. 2005; 84:77-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2004.06.011.

[11] Audsley E, Pearn KR, Simota C, Cojocaru G, Koutsidou E, Rounsevell MDA, et al. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE, editors. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. 273-313.

[12] Olesen JE, Bindi M. Consequences of climate change for European agricultural productivity, land use and policy. Eur J Agron.2002; 16:239-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1161-0301(02)00004-7.

[13] Tubiello FN, Rosenzweig C, Goldberg RA, Jagtap S, Jones JW. Effects of climate change on US crop production: simulation results using two different GCM scenarios. Part I: wheat, potato, maize, and citrus. Clim Res.2002; 20:259-70. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr020259.

[14] Reilly J, Tubiello FN, McCarl BA, Abler DG, Darwin R, Fuglie K, et al. US agriculture and climate change: new results. Clim Change.2003; 57:43-69. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022103315424.

[15] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

[16] Kumar KK, Kumar KR, Ashrit RG, Deshpande NR, Hansen JW. Climate impacts on Indian agriculture. Int J Climatol.2004;24:1375-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1081.

[17] Sivakumar MVK, Das HP, Brunini O. Impacts of present and future climate variability and change on agriculture and forestry in the arid and semi-arid tropics. Climate Change. 2005; 70:31-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-5937-9.

[18] Lobell DB, Burke MB. Why are agricultural impacts of climate change so uncertain? The importance of temperature relative to precipitation. Environ Res Lett. 2008; 3:034007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/3/3/034007.

[19] Ciais P, Reichstein M, Viovy N, Granier A, Ogee J, Allard V, et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature. 2005; 437:529-33. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03972.

[20] Stott PA, Stone DA, Allen MR. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature. 2004; 432:610-4. https://doi.org/10.1038/.nature03089.

[21] Porter JR, Semenov MA. Crop responses to climatic variation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005; 360:2021-35. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1752.

[22] Wheeler TR, Craufurd PQ, Ellis RH, Porter JR, Prasad PVV. Temperature variability and the yield of annual crops. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2000; 82:159-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00224-3.

[23] Wollenweber B, Porter JR, Schellberg J. Lack of interaction between extreme high-temperature events at vegetative and reproductive growth stages in wheat. J Agron Crop Sci. 2003; 189:142-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-037X.2003.00025.x.

[24] Porter JR, Gawith M. Temperatures and the growth and development of wheat: a review. Eur J Agron. 1999; 10:23-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1161-0301(98)00047-1.

[25] Wilhite DA. Drought. In: Encyclopedia of Earth System Science. Vol. 2. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. p. 81-92.

[26] Kettlewell PS, Sothern RB, Koukkari WL. UK wheat quality and economic value are dependent on the North Atlantic Oscillation. J Cereal Sci. 1999; 29:205-9. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcrs.1999.0258.

[27] Kumar V, Naidu MM. Development in coffee biotechnology – in vitro plant propagation and crop improvement. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2006; 87:49-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-006-9134-y.

[28] HM Treasury. Green biotechnology and climate change. Euro Bio. 2009;12. Available from: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/15021072/Green-Biotechnology-and-Climate-Change.

[29] Mneney EE, Mantel SH, Mark B. Use of random amplified polymorphic DNA markers to reveal genetic diversity within and between populations of cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.). J Hort Sci Biotechnol. 2001; 77(4):375-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/.14620316.2001.11511380.

[30] Sharma HC, Crouch JH, Sharma KK, Seetharama N, Hash CT. Applications of biotechnology for crop improvement: Prospects and constraints. Plant Sci. 2002; 163(3):381-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00133-4.

[31] Johanson A, Ives CL. An inventory of the agricultural biotechnology for Eastern and Central Africa region. Michigan: Michigan State University; 2001. p. 62.

[32] Morris EJ. Modern biotechnology: Potential contribution and challenges for sustainable food production in sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability. 2011; 3:809-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su3060809.

[33] Vallad GE, Goodman RM. Systemic acquired resistance and induced systemic resistance in conventional agriculture. Crop Sci. 2004; 44:1920-34. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2004.1920.

[34] Sarin R, Sharma M, Sinharay S, Malhotra RK. Jatropha-palm biodiesel blends: An optimum mix for Asia. Fuel. 2007; 86(10-11):1365-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2006.11.040.

[35] Lua H, Liu Y, Zhou H, Yang Y, Chen M, Liang B. Production of biodiesel from Jatropha curcas L. oil. Comput Chem Eng. 2009; 33(5):1091-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2008.09.012.

[36] Jain S, Sharma MP. Prospects of biodiesel from Jatropha in India: A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2010; 14(2):763-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2009.10.005.

[37] Lybbert T, Sumner D. Agricultural technologies for climate change mitigation and adaptation in developing countries: Policy options for innovation and technology diffusion. ICTSD-IPC Platform on Climate Change, ATS Policy Brief. 2010; (6). Available from: http://ictsd.org/i/publications/77118/

[38] Maeder P, Fliessbach A, Dubois D, Gunst L, Fried P, Niggli U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science. 2002; 296(5573):1694-7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1071148.

[39] Brookes G, Barfoot P. GM crops: Global socio-economic and environmental impacts 1996-2008. Dorchester: PG Economics; 2008.

[40] Zahran HH. Rhizobia from wild legumes: Diversity, taxonomy, ecology, nitrogen fixation and biotechnology. J Biotechnol. 2001; 91:143-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00342-X.

[41] Kennedy IR, Tchan YT. Biological nitrogen fixation in non-leguminous field crops: Recent advances. Plant Soil. 1992; 141:93-118. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00011312.

[42] Paau AS. Improvement of Rhizobium inoculants by mutation, genetic engineering and formulation. Biotechnol Adv. 2002; 9(2):173-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/0734-9750(91)90002-D.

[43] Saikia SP, Jain V. Biological nitrogen fixation with non-legumes: An achievable target or a dogma? Curr Sci. 2007; 93(3):317-22.

[44] Yan Y, Yang J, Dou Y, Chen M, Ping S, Peng J, et al. Nitrogen fixation island and rhizosphere competence traits in the genome of root-associated Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008; 105(21):7564-9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801093105.

[45] Johnson JM, Franzluebbers AJ, Weyers SL, Reicosky DC. Agricultural opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Environ Pollut. 2007; 150(1):107-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.030.

[46] Barrows G, Sexton S, Zilberman D. Agricultural biotechnology: The promise and prospects of genetically modified crops. J Econ Perspect. 2014; 28(1):99-120. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.1.99.

[47] Hong Z, Lakkineni K, Zhang K, Verma DPS. Removal of feedback inhibition of delta-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase results in increased proline accumulation and protection of plants from osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2000; 122:1129-36. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.122.4.1129.

[48] Jaglo KR, Kleff S, Amunsen KL, Zhang X, Haake V, Zhang JZ, et al. Components of Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration response element binding factor cold-response pathway are conserved in Brassica napus and other plant species. Plant Physiol. 2001; 127:910-7. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.010548.

[49] Yamanouchi U, Yano M, Lin H, Ashikari M, Yamada K. A rice spotted leaf gene Sp17 encodes a heat stress transcription factor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002; 99:7530-5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.112209199.

[50] Hsieh TH, Lee JT, Yang PT, Chiu LH, Charng YY, Wang YC, et al. Heterologous expression of Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration response element binding factor 1 gene confers elevated tolerance to chilling and oxidative stresses in transgenic tomato. Plant Physiol. 2002; 129:1086-94. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.003442.

[51] Zhu JK. Plant salt tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2001; 6(2):66-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0.

[52] West TO, Post WM. Soil organic carbon sequestration rates by tillage and crop rotation: A global analysis. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2002; 66:930-46. https://doi.org/10.3334/CDIAC/tcm.002.

[53] Fawcett R, Towery D. Conservation tillage and plant biotechnology: How new technologies can improve the environment by reducing the need to plow. CTIC, USA; 2003. Available from: http://www.ctic.purdue.edu/CTIC/Biotech.html.

[54] Brimner TA, Gallivan GJ, Stephenson GR. Influence of herbicide-resistant canola on the environmental impact of weed management. Pest Manag Sci. 2004; 61(1):47-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.967.

[55] Kleter GA, Harris C, Stephenson G, Unsworth J. Comparison of herbicide regimes and the associated potential environmental effects of glyphosate-resistant crops versus what they replace in Europe. Pest Manag Sci. 2008; 64:479-88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1513.

[56] Arif M, Jan T, Munir H, Rasul F, Riaz M, Fahad S, et al. Climate-smart agriculture: Assessment and adaptation strategies in changing climate. In: Global Climate Change and Environmental Policy: Agriculture Perspectives. 2020. p. 351-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/.978-981-13-9570-3_12.

[57] Grigorieva E, Livenets A, Stelmakh E. Adaptation of agriculture to climate change: A scoping review. Climate. 2023; 11(10):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11100202.

[58] Li Z, Taylor J, Frewer L, Zhao C, Yang G, Li Z, et al. A comparative review of the state and advancement of Site-Specific Crop Management in the UK and China. Front Agric Sci Eng. 2019; 6(2):116-36. https://doi.org/10.15302/J-FASE-2018240.

[59] Meena RS, Kumar S, Yadav GS. Soil carbon sequestration in crop production. In: Nutrient dynamics for sustainable crop production. 2020. p. 1-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8660-2_1.

[60] Yang Y, Tilman D. Soil and root carbon storage is key to climate benefits of bioenergy crops. Biofuel Res J. 2020; 7(2):1143-8. https://doi.org/10.18331/BRJ2020.7.2.2.

[61] Edgerton MD. Increasing crop productivity to meet global needs for feed, food and fuel. Plant Physiol. 2009; 149:7-13. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.130195.

[62] Bianchi FJJA, Booij CJH, Tscharntke T. Sustainable pest regulation in agricultural landscapes: A review on landscape composition, biodiversity and natural pest control. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2006; 273:1715-27. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3530.

[63] Cheung PCK, Chang ST. Overview of mushroom cultivation and utilisation as functional foods. In: Cheung PCK, editor. Mushrooms as Functional Foods. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2009. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470367285.ch1.

[64] He P, He M, Dou T, Wang Y, Ma L, Yin X, et al. Integrated physiological and transcriptome analysis revealed the roles of phytohormone signaling in response to salt stress in tomato. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24:4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054386.

[65] Gouiaa S, Khoudi H, Leidi EO, Pardo JM, Masmoudi K. Expression of wheat Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter TNHXS1 and H⁺-pyrophosphatase TVP1 genes in tobacco from a bicistronic transcriptional unit improves salt tolerance. Plant Mol Biol. 2012; 79:137-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/.s11103-012-9901-6.

[66] Sheffield J, Wood EF, Roderick ML. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature. 2012; 491:435-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11575.

[67] Sun FB, Roderick ML, Farquhar GD. Changes in the variability of global land precipitation. Geophys Res Lett. 2012; 39: L19402. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL053369.

[68] Harrison MT, Tardieu F, Dong Z, Messina CD, Hammer GL. Characterizing drought stress and trait influence on maize yield under current and future conditions. Glob Change Biol. 2014; 20:867-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12381.

[69] Olesen JE, Trnka M, Kersebaum KC, Skjelvåg AO, Seguin B, Peltonen‐Sainio P, et al. Impacts and adaptation of European crop production systems to climate change. Eur J Agron. 2011; 34(2):96-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2010.11.003.

[70] Mickelbart MV, Hasegawa PM, Bailey-Serres J. Genetic mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance that translate to crop yield stability. Nat Rev Genet. 2015; 16(4):237-51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3901.

[71] Ewert F, Rotter RP, Bindi M, Webber H, Trnka M, Kersebaum KC, et al. Crop modelling for integrated assessment of risk to food production from climate change. Environ Model Softw. 2015; 72:287-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.12.003.

[72] Tardieu F, Simonneau T, Muller B. The physiological basis of drought tolerance in crop plants: A scenario-dependent probabilistic approach. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018; 69:733-59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040440.

[73] Zhang Q, Bartels D. Molecular responses to dehydration and desiccation in desiccation-tolerant angiosperm plants. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69:3211-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery131.

[74] Blum A, Tuberosa R. Dehydration survival of crop plants and its measurement. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69:975-81. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/.ery018.

[75] Borrás L, Vitantonio-Mazzini LN. Maize reproductive development and kernel set under limited plant growth environments. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69(13):3235-43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery157.

[76] Chenu K, Cooper M, Hammer GL, Mathews KL, Dreccer MF, Chapman SC. Integrating modelling and phenotyping approaches to identify and screen complex traits – transpiration efficiency in cereals. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69(13):3181-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery071.

[77] Tricker PJ, El-Habti A, Schmidt J, Fleury D. The physiological and genetic basis of combined drought and heat tolerance in wheat. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69(13):3195-210. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery081.

[78] Salvi S, Tuberosa R. The crop QTLome comes of age. Curr Opin Biotechnoology 2015; 32:179-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/.j.copbio.2014.11.020.

[79] Marra MC, Piggott NE, Goodwin BK. The anticipated value of SmartStax™ for US corn growers. AgBioForum. 2010; 13(1):1-12.

[80] Que Q, Chilton MDM, de Fontes CM, He C, Nuccio M, Zhu T, et al. Trait stacking in transgenic crops: Challenges and opportunities. GM Crops. 2010; 1(4):220-9. https://doi.org/10.4161/gmcr.1.4.13439.

[81] Christou P. Strategies for variety-independent genetic transformation of important cereals, legumes and woody species utilising particle bombardment. Euphytica. 1995; 85:13-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00023926.

[82] Bradow JM, Davidonis GH. Quantitation of fibre quality and the cotton production-processing interface: a physiologist’s perspective. J Cotton Sci. 2000; 4:34-64

[83] Campbell BT, Jones MA. Assessment of genotype × environment interactions for yield and fiber quality in cotton performance trials. Euphytica. 2005; 144:69-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-005-4336-7.

[84] Huang J, Hao H. Effects of climate change and crop planting structure on the abundance of cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner). Ecol Evol. 2020; 10(3):1324-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5986.

[85] Narayanamoorthy A, Renuka C, Sujitha KS. How does Bt cotton perform in rainfed areas? Agric Econ Res Rev. 2020; 33(1):53-60. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0279.2020.00006.3.

[86] Flachs A. Redefining success: The political ecology of genetically modified and organic cotton. J Polit Ecol. 2016; 23(1):49-70. https://doi.org/10.2458/v23i1.20179.

[87] Tokel D, Genc BN, Ozyigit II. Economic impacts of Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) cotton. J Nat Fibers. 2021; 19(12):4622-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2020.1870613.

[88] ISAAA in 2019: Accomplishment Report. Brief 55: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2019. Manila, Philippines: International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA); 2019.

[89] Kranthi KR, Stone GD. Long-term impacts of Bt cotton in India. Nat Plants. 2020; 6(3):188-96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-0615-5.

[90] Najork K, Friedrich J, Keck M. Bt cotton, Pink Bollworm, and the political economy of sociobiological obsolescence: Insights from Telangana, India. Agric Human Values. 2022; 39(3):1007-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10301-w.

[91] Zhang W, Lu Y, van der Werf W, Huang J, Wu F, Zhou K, et al. Multidecadal, county-level analysis of the effects of land use, Bt cotton, and weather on cotton pests in China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018; 115(33): E7700-E7709. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721436115.

[92] Leridon H. World population outlook: Explosion or implosion? Popul Soc. 2020; 573:1-4. https://doi.org/10.3917/popsoc.573.0001.

[93] Shahid SA, Zaman M, Heng L. Soil Salinity: Historical Perspectives and a World Overview of the Problem. In: Guideline for Salinity Assessment, Mitigation and Adaptation Using Nuclear and Related Techniques. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 43-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96190-3_2.

[94] Chinnusamy V, Jagendorf A, Zhu J. Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci. 2005; 45:437-48. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2005.0437.

[95] Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J. Changes in plant response to NaCl during development of rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties differing in salinity resistance. J Exp Bot. 1995; 46:1843-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/46.12.1843.

[96] Todaka D, Nakashima K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Toward understanding transcriptional regulatory networks in abiotic stress responses and tolerance in rice. Rice. 2012; 5:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1939-8433-5-6.

[97] Kumar K, Kumar M, Kim SR, Ryu H, Cho YG. Insights into genomics of salt stress response in rice. Rice. 2013; 6:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1939-8433-6-27.

[98] Horie T, Karahara I, Katsuhara M. Salinity tolerance mechanisms in glycophytes: An overview with the central focus on rice plants. Rice. 2012; 5:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1939-8433-5-11.

[99] Agarwal P, Parida SK, Raghuvanshi S, Kapoor S, Khurana P, Khurana JP, et al. Rice improvement through genome-based functional analysis and molecular breeding in India. Rice. 2016; 9(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-015-0073-2.

[100] Hoang TML, Tran TN, Nguyen TKT, Williams B, Wurm P, Bellairs S, et al. Improvement of salinity stress tolerance in rice: challenges and opportunities. Agronomy. 2016; 6(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy6040054.

[101] Kaur N, Pati PK. Integrating classical with emerging concepts for better understanding of salinity stress tolerance mechanisms in rice. Front Environ Sci. 2017; 5:42. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2017.00042.

[102] Abdul-Razak M, Kruse S. The adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change in the Northern Region of Ghana. Clim Risk Manag. 2017; 17:104-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.06.001.

[103] Khlestkina EK, Shumnyi VK. Prospects for application of breakthrough technologies in breeding: The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing. Russ J Genet. 2016; 52(7):676-87. https://doi.org/10.1134/S102279541607005X.