Article Contents

Sustainability in Global Supply Chains: A Study on the Impact of Distributed Ledger Technology on Ethical Sourcing and Consumer Trust

⬇ Downloads: 27

1College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Received: 08 September, 2025

Accepted: 24 December, 2025

Revised: 24 December, 2025

Published: 26 December, 2025

Abstract:

Aims and Objective: The study examined how Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) can play a role in business ethics and how the ethical conduct of business can help consumers have more confidence in the global supply chain. It further explored how the adoption of Ethical Sourcing Practices (ESP) mediates the relationship between DLT adoption and consumer confidence in the Saudi Arabian context.

Methods: A purposive sampling approach was followed in accordance with a positivist approach. In order to gather the information among 355 respondents, an online survey was distributed, and the data have been analysed with the help of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in SmartPLS 4.0.

Findings: The findings of the PLS-SEM established that DLT significantly predicted Ethical Sourcing Practices (0.641, p < 0.001) whereas ethical sourcing practices also had significant and positive impact on perceived consumer trust (0.518, p < 0.001). The direct effect of DLT on perceived consumer trust was significantly positive (β = 0.325, p < 0.001). The model explains 41% of ESP and 59% of trust. Additionally, a significant indirect effect of DLT on perceived consumer trust via ethical sourcing practices was confirmed, indicating partial mediation (β = 0.331, p < 0.001).

Results: This research combined model that correlates DLT adoption, ethical sourcing practices, and perceived consumer trust using the TOE and signalling theories. It uses data on multi-industry supply chains from multi-industry surveys (Saudi Vision 2030) to illustrate the capacity of blockchain-enabled sourcing capabilities and turn it into a trust gain.

Limitation: The research involves the cross-sectional survey data, which would allow finding statistical correlations but would not allow to establish the causality. Additionally, the results may not apply to all individuals in the industry.

Keywords: Distributed ledger technology, ethical sourcing practices, perceived consumer trust, supply chain management, TOE framework, PLS-SEM.

1. INTRODUCTION

Global supply chains that have supported world trade for over 30 years have generated social and environmental harms, including high carbon emissions, labour mistreatment, and weak regulation (Kshetri, 2021; McGrath et al., 2021). These harms become a governance problem in Saudi Arabia, which strives to establish itself as a logistics and manufacturing hub under Vision 2030: how companies can prove their sourcing practices are in line with the ethical requirements of regulators, investors, and consumers. Sustainability is not merely a reporting desire but an issue of presence and responsibility because enterprises have to demonstrate the dynamic impact of the remote production process on the population and the environment (Asante et al., 2021). The essential issue is whether companies have enough reasons to act in an ethical way because audits and corporate reporting do not necessarily provide the opportunity to see what happens when the organization has a complex network of suppliers in foreign countries. (Mohammed et al., 2024). This task is magnified in the Gulf economies, where fast trade development, multi-tier supply chain design and foreign investment are in collision with less empirical examination against sourcing information.

The visibility and trust problems are addressed directly in debates over Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT). (Wei, 2023) described that Coded as blockchain, most commonly, DLT stores the chronological records of transactions, which are impossible to modify and distributed among the members of a network. (Vinayavekhin et al., 2024) demonstrated that they are able to track a product throughout supply chain transitions so that brands can document how a raw material was transformed into a finished product. (Bernards et al., 2024) opined that ethical performance indicators are perhaps more legitimate when the certifications and environmental assertions are registered in a registry that cannot be tampered with. The theoretical debate is whether or not this infrastructural faith in code and distributed consensus substitutes, augments or does not alter long-standing suspicions regarding corporate self-reporting. Arguably, the case of DLT simply moving the paper trails online without altering the authorities over information and the management of exceptions. In that case, it may reproduce old assurance problems in a new technical form rather than solving them.

The Saudi setting sharpens this tension because ambitious sustainability objectives coexist with rapid investment in digital infrastructure. (Al-Kubaisy & Al-Somali, 2023) found technology, organisational, and environmental antecedents of adoption of blockchain in Saudi logistics. However, the impact of ledgers in monitoring and reporting of ethical performance was not clear. Vision 2030 and programmes associated with it require responsible development and enhanced environmental, social, and governance disclosure. However, they fail to describe how companies can abandon the paper-based and opaque controls with verifiable digital records of sourcing (Government of Saudi Arabia, 2025). In the absence of data that DLT adoption alters the informational basis of trust by decreasing dependence on untestable supplier claims and semi-regular audits; sustainability pledges will stay unlinked to daily procurement choices. The research fulfils a gap in the literature by outlining how Saudi companies can convert these intentions into tangible digital trust systems in the supply chains that would be observable among the external stakeholders.

Loyalty to consumers goes beyond legal conformity and brand loyalty. (Nurgazina et al., 2021) opined that trust will be enhanced as the stakeholders have the ability to match sustainability assertion with credible information about product origin and behaviour. (Joo & Han, 2021) demonstrated that the consumers will be ready to pay higher prices to goods which seem to be produced in a responsible fashion, although this intention will not be strong when they suspect green washing or verifiability of advertisements. According to (Varma et al., 2024), more meaningful evidence could be delivered by the DLT as it allows conducting a closer examination of the sourcing activities. However, (Mohamed et al., 2023) observed that research offers limited insight into whether blockchain-based transparency alters how trust is formed or whether stakeholders continue to rely on signals such as price, brand image, and certification logos. Against this background, the study examines how DLT use in Saudi supply chains influences ethical sourcing and perceived consumer trust, clarifies how digital and conventional trust signals interact, and informs debates on implementing Vision 2030 sustainability goals at the firm level.

As (Toukabri & Chaouachi, 2025) established, within the broader concept of technological transparency, local consumers are positively affected by blockchain-provenance. Simultaneously, the studies on the DLTs adoption are inclined to pay attention to the technical affordances, including traceability, security, and data integrity, instead of the way in which the mentioned features may modify ethical visibility and the formation of trust along the chain (McGrath et al., 2021; Nurgazina et al., 2021). Thus, this article presents not just a tool in logistics but also a possible means of introducing a new approach to building trust within the chain, and it posits whether, in Saudi supply chains, ledger-enabled ethical sourcing can provide a measurably more substantial boost to consumer confidence.

The research holds useful implications to practice and policy by identifying the opportunity of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) to support ethical sourcing and consumer confidence in global supply chains. Through highlighting the positive role of the introduction of DLT in shaping perceived consumer trust, in particular mediated by the adoption of ethical sourcing practices, the research can be used as an actionable resource to help companies enhance their transparency and sustainability efforts. The results highlighted the necessity of harmonization of technological innovations and ethical governance and, specifically, the Saudi Vision 2030 that places sustainable development and openness in the spotlight. The research provided a clear avenue towards using the DLT in the supply chain strategy to enhance consumer confidence. Moreover, it gives policy-makers an empirical basis to implement DLT-based structures of more responsible and ethically transparent supply chains in line with other sustainability agendas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability in Global Supply Chains

Conventional discussions on supply chains have moved past cost and delivery reliability to include how companies are revamping far off manufacturing into transparent and responsible operations. (Heldt & Pikuleva, 2025) suggest that accountability is required of the stakeholders, such as customers and NGOs, by measuring the social and environmental performance. Although they bring up the point about verification, they fail to address the level to which the third-party verification is being adopted, which very crucial considering the increased relevance of credibility in responsible is sourcing. This argument is stronger as (Almabrok, 2023) asserts than how credible responsible products can be offered to appeal to more consumers who are willing to pay a higher price, but does not explain how these products could be delivered according to verifiable standards. (Park & Li, 2021) describe regulatory frameworks like the European due diligence regimes as significant but without exploring the local issue of the non-European markets like the Gulf. According to (Mohammed et al., 2024), the disadvantages of the paper-based audits are to detect the misconducts but the findings are specific to the African context and do not represent the regulation landscape of the Gulf economies. This under scrutiny demonstrates a lack of knowledge of how Gulf purchasers can successfully convert ethical sourcing pledges into daily supervision, a key concern to resource-endowed, import-sensitive economies such as Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) Overview

Distributed Ledger Technology is often suggested as a way of restructuring the supply chain information capture and control. (Wei, 2023) explains that Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) in its usual form, that is, blockchain, is the process of structuring transactions in time-stamped blocks, thereby eliminating manipulations of data unilaterally. Although this offers a high level of security, the literature does not critically examine the limitations of the practicality of the DLT adoption. The study by (Antal et al., 2025) concluded that blockchain brought about visibility in textile production in Vietnam, but the study bases its findings on cross-sectional surveys and self-reported data, which does not allow concluding about causal links. In the same fashion, (Vazquez et al., 2024) relate the implementation of blockchains to increased consumer confidence in Europe, but also their research has a limitation of self-reported data, which is susceptible to bias. (McGrath et al., 2021) emphasise the fact that good governance is the only way to ensure transparency, and possible risks include organisational resistance and lack of interoperability, but does not answer the question of how these issues are reflected in various regulatory settings. (Mubarik et al., 2021) pay attention to smart contracts but ignore the possibility of conflict or inaccuracy of the information, which may erode the validity of the system. Moreover, the articles do not address the socio-political intricacies of introducing DLT in areas such as Saudi Arabia that state regulation and digital change have to be synchronized.

2.3. Ethical Sourcing in Global Supply Chains

Ethical sourcing is a terminology used to refer to procurement processes aimed at observing labour rights, minimising the environmental impact and benefiting the local communities, yet how to operationalise this concept is still difficult. There are several strengths and weaknesses of the literature on responsible sourcing and DLT in terms of the study of ethical practices and transparency. According to (Mancini et al., 2021), the responsible sourcing standards, e.g., the requirement of fair wages and safety, are applied inconsistently across jurisdictions. These demands increased homogenous practices. Nevertheless, this specific research does not consider the fact that such standards can be extremely challenging to enforce in low-regulation settings where audits can be few and far between and records can be easily doctored as highlighted by (Kannan, 2021). According to (Zu Ermgassen et al., 2022), even the commitments of companies, such as zero-deforestation, may be undermined by intermediaries, and the suggestion is that a contract and codes fail to help uphold one such commitment. These studies identify the need for long-term and systematic monitoring as an imperative requirement. Yet, they fail critically to assess the practical obstacles to their implementation, particularly in highly diverse regulatory contexts. DLT is promoted as a traceability tool, which provides certification that is not tampered and record-keeping (Mubarik et al., 2021), but has its limitations. Small vendors can be omitted due to the absence of digital capabilities, and conflicts in the interpretation of data cannot be resolved (Zu Ermgassen et al., 2022). In terms of the signalling theory, although the transparency is enhanced through DLT-based traceability, institutional trust is required to designate it, which is not always present (Wei, 2023). Moreover, the research has also ignored socio-political and infrastructural challenges in implementing DLT in places like Saudi Arabia, where governance structures have been changing (Al-Kubaisy & Al-Somali, 2023; Asante et al., 2021). These gaps suggest that while DLT has potential, its impact upon perceived consumer trust is still uncertain and dependent on broader systemic reform.

2.4. Consumer Trust and Transparency

Consumer trust is the belief that a firm’s statements about a product’s origin and behaviour are reliable enough to inform decision-making and justify continued involvement in the relationship. According to (Singh & Sharma, 2023) facilitating sustainability by using empty slogans loses credibility by emphasising the role of facts in supporting sustainability arguments. Nevertheless, this emphasis on slogans overlooks the challenges of ensuring the sustainability claims, in particular, in areas where regulation is weak. (Veltri et al., 2023) show that with clear and accessible information on digital platforms, transparency and trust may improve, which is also not the case in their study in regard to the possible barriers to accessibility or digital divide, especially in small businesses. DLT can help resolve it by offering verifiable, time-stamped records, which allow the stakeholders to trace sourcing practices, as it was demonstrated in the study by (Da Silva & Moro, 2021), through QR codes. Although the prospect of DLT in increasing transparency can be identified, it is constrained by its use of digital infrastructure that might lock out small suppliers who might be unable to use the technology (Mubarik et al., 2021). (Kraft et al., 2022) also emphasise that greater disclosures lead to a higher level of perceived consumer trust, but do not consider how inconsistency or lack of full data may undermine trust, especially when DLT is not universally used and trusted. This disconnect suggests that in as much as DLT can create a sense of transparency, its usefulness in the development of perceived consumer trust relies on detailed, trusted, and universally available information.

2.5. DLT and Ethical Sourcing

Some of the studies have already indicated that the use of DLT can facilitate the process of responsible sourcing. The conclusion made by (Özkan et al., 2024) was that blockchain helps in controlling ethical chain operations throughout the supply chain. Another quote presented by (Zhou et al., 2022) is that smart contracts are only released to make a payment and verify compliance when operations of a company can be considered ethical, which eliminates the risk. (Nguyen et al., 2022) also conducted research to identify the barriers to the DLT adoption. They involve setting up expensive systems, experiencing difficulties exchanging information through the supply chain, and challenges with how and when the data should be protected. There are often not enough technical experts in low- and middle-income countries to help with the setup and use of DLT (Gorbunova et al., 2022). Even then, most people believe that DLT is a reliable way to maintain honest and fair input records. It helps ensure data security and ensures that information is shared with everyone held responsible.

2.6. Empirical Insights and Theoretical Relationship

The recent research is united in considering that the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) can contribute to the global supply chain substantially in terms of sustainability performance when analysed within the frames of the Technology-Organisation-Environment (TOE) theory, the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) model, and the signalling theory. Several empirical studies have examined blockchain adoption using diverse methods and national contexts. Drawing on a TAM-TOE framework, (Liu et al., 2024) interviewed Malaysian agribusiness companies and used PLS-SEM to establish security-privacy capabilities, policy support, and top-management support as the main facilitators of DLT adoption. Their single-respondent, cross-sectional design, although effective in showcasing the main organisational and environmental drivers, lacks causal depth and might not be applicable to other sectors other than the agribusiness. (N’Dri & Su, 2024) undertook a fuzzy-set analysis of data collected on 243 exporting SMEs where technological readiness and external pressures were found to have a particular set of configurations that produces high transparency results. Their configurational approach emphasises the effects of contingencies but fails to examine how firms change these configurations over time. There are also additional evidences on the issue by the commodity-specific and strategic analyses. (Mohammed et al., 2024) examined the relationship between blockchain application and ethical sourcing, testing, and transparency by conducting a multi-respondent survey in the cocoa sector in Ghana, adjusting the impact of the firm and CSR orientation. There is also a risk that the cross-industry dynamics is tainted by their obsession with one commodity. The game-theoretic model created by (Biswas et al., 2023) demonstrates that manufacturers invest in DLT when reputational benefits of traceability outweigh the incremental cost of sustainability of traceability, but its abstract nature does not take into account the difficulty of the implementation in the real world. A PLS-SEM survey of Italian consumers by (Sepe, 2024) demonstrated that provenance labels created with blockchain enhance the purchase intentions of consumers by enhancing transparency and trust. Nevertheless, the intention measure is incomplete in representing real behaviour.

2.7. Research Gap

The study is progressively scrutinizing the capacity of distributed ledger technology to enhance the traceability, transparency, and perceived consumer trust in supply chains; these are some of the gaps. First, recent researches, including (Mohammed et al., 2024; N’Dri & Su, 2024; and Sepe, 2024) are largely based on cross-sectional surveys in commodity chains in Southeast Asia, Europe, and Africa and do not provide much evidence on the Middle Eastern markets where rapid sustainability reforms are underway as part of Saudi Vision 2030. Second, the majority of the contributions dwell upon perceived transparency, traceability, and purchase intent, but it does not provide a deep understanding of the perception of professionals in Saudi Arabia regarding the application of DLT to generate ethical sourcing and the chance of such a perception to increase perceived consumer trust. Third, the prevailing configurationally and theoretical approaches (TOE, DOI, signalling theory) are rarely disaggregated as to the manner in which the DLT-based smart contracts and real-time data exchange are incorporated in organisational routines and power relations. The current research, thus, takes a quantitative survey of supply chain professionals in Saudi Arabia as a method of filling contextual and perceptual gaps, and recognising that objective ESG indicators, behavioural outcome, and qualitative tracing of processes remain essential research priorities in the future. It analyses the evaluation of the respondents on the contribution of DLT to ethical sourcing practices, transparency, and perceived consumer trust in Saudi-based supply chains through structured scales which reflect attitudes and intentions.

2.8. Theoretical Framework

The case is based on the Technology-Organisation-Environment paradigm of Technology-Organisation-Environment (TOE). TOE is also chosen instead of individual-level models like TAM or UTAUT since the Distributed ledger technology (DLT) adoption to supply chains in Saudi is a firm-level, strategic decision that depends on technological attributes, organisational capabilities and regulatory and market pressures (Al Hadwer et al., 2021). In that paradigm, DLT is a type of infrastructural capability, the perceived relative advantage of which, in creating tamper-resistant and shareable records, should dominate the cost and complexity of integration (Chittipaka et al., 2023). In transparency theory views such infrastructures as devices that reconfigure information flows, monitoring, and sanctions. At the same time, capability perspectives emphasise how digital assets are mobilised through routines to support ethical sourcing and compliance. The proposed mediation, in which ethical sourcing practices transmit the effect of DLT to perceived consumer trust, recognises that ledgers do not create trust directly; instead, they enable more consistent enforcement of labour, environmental, and provenance standards that can be credibly disclosed to external audiences. Signalling theory explains how these verifiable disclosures and traceability certifications operate as market signals under conditions of information asymmetry, while also allowing for scepticism where institutional guarantees are weak. The resulting, still simplified, causal path is that DLT adoption (TOE and capability) enhances transparency, supports more reliable ethical sourcing behaviour, and thereby strengthens perceived consumer trust in Saudi-based supply chains. Trust remains multidimensional, but this model isolates a pathway.

H1: In the Saudi Arabian context, firm-level of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) adoption is positively associated with perceived Consumer Trust (CT).

The signalling theory claims that the available verifiable provenance information would reduce the information asymmetry and increase the trust of the stakeholders. To define how permissioned-ledger QR codes of product packaging influence perceived transparency and trust, (Laraichi, 2020) carried out PLS-SEM survey to establish how such a decision affects product packaging. Despite the fact that the research confirms the use of blockchain-based cues enhances the perceptions, the self-reported purchase intentions and use of a single European shopping scenario limit the generalisation of the study to actual buying behaviour and non-Western contexts. (Rapezzi et al., 2024) performed three experiments online across the EU countries and controlled the retailer transparency by showing the information through blockchain. Their results show that transparency increases the perceived quality and the level of trust in the retailer, which, subsequently, results in the intention to repurchase it; though, the hypothetical character of the situations does not necessarily mirror the real-life decision-making processes. On the other hand, the paper discusses the reaction of consumers to ethical sourcing disclosures through surveys about the use of DLT in Saudi Arabia combined with historical ESG indicators to comment on the influences of transparency on trust-based behaviours within the constantly evolving sustainability context.

H2: Within Saudi supply chains, Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) is positively associated with Ethical Sourcing Practices (ESP).

The results of the survey by (Liu et al., 2024) of agricultural supply organisations in Henan Province of China indicated that the level of blockchain adoption had an influence on traceability and monitoring of suppliers using the PLS-SEM. In their opinion, those companies that have applied the ledger more actively declare a greater level of end-to-end product visibility and tighter control of the upstream partners. However, the limited and regionally specific sample of the study and the respondent design adopted in the study undermine the statistical strength of the study and the common-method bias, and are insufficient to ascribe such functional advantages to sustainability or a large-scale ethical sourcing impact of the study.

H3: In Saudi Arabia, perceived ethical sourcing practices signal and mediate the effect of DLT adoption on perceived consumer trust.

(Al Hadwer et al., 2021) conducted an online between-subjects study with Jordanian consumers to investigate the impact of disclosures about living wage and carbon certifications with smart contract verification on trust. They have enrolled that sourcing information determined by blockchain grew the faith and intentions of loyalty. However, external validity is restricted due to the utilization of self-reported intentions and one country, one product design. This data is the indication that the provenance indicators by blockchain may enhance the confidence in buyers, yet the existing research is focused on experimentation algorithms in certain spheres and does not imply real buying behaviour. The research gaps are filled through the survey of Saudi consumers and the correlation of revealed ethical sourcing facilitated by DLT and perceived trust or the actual sales performance in the context of the Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 on sustainability.

2.9. Conceptual Framework

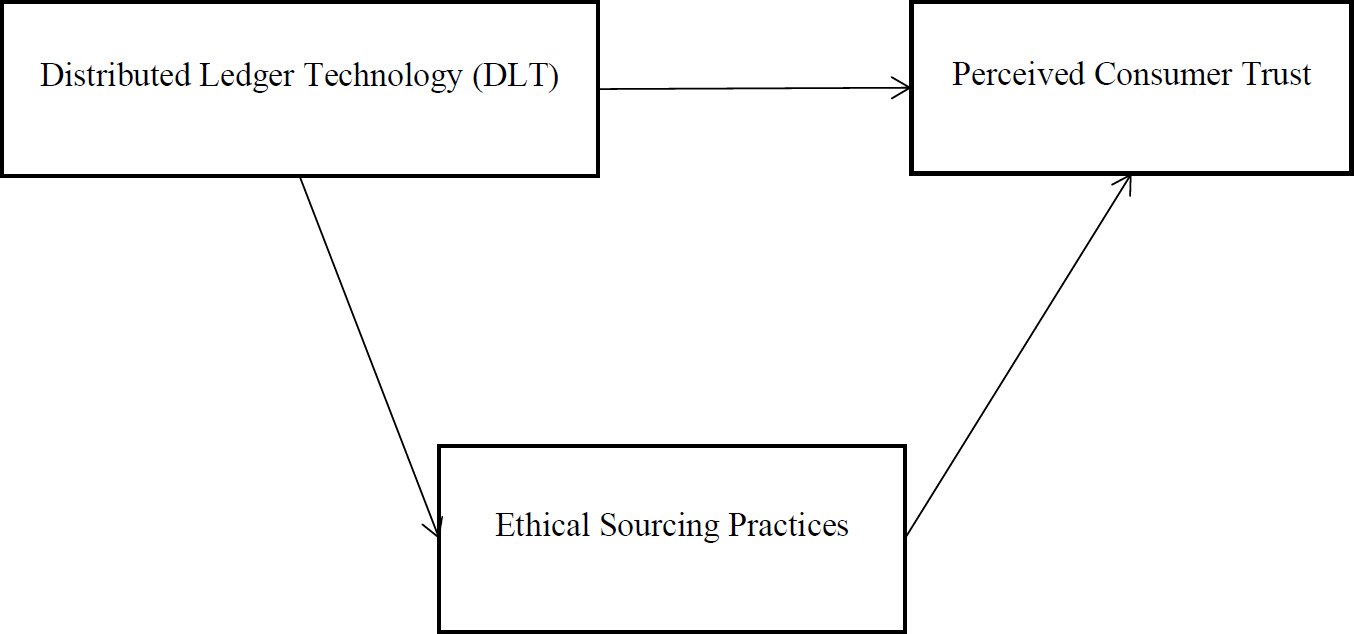

The hypotheses are that adopting the DLT through the conceptual model not only drives change in ethical sourcing but also increases perceived consumer trust. (Fig. 1) shows that the concept of DLT would directly and indirectly build perceived consumer trust through ethical ingredient sourcing.

Fig. (1). Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

The explanatory design used in this quantitative research was cross-sectional to determine theory-based relationships among professionals in the supply chain industry of Saudi Arabia. In 2024, a structured online survey was conducted via Google Forms to 550 logistics, procurement, and compliance professionals in manufacturing, petrochemical, and retail companies in Saudi Arabia to collect data on DLT evaluation and sourcing oversight. Three hundred fifty-five questionnaires were returned to the researcher (response rate = 64.54%). Reported “ESG indicators” reflect perceptions rather than actual performance. The perceived consumer trust construct captures professionals’ views of how consumers might respond, not consumer behaviour. Non-response bias was assessed by comparing early and late respondents on firm size and role; no significant differences emerged. Data that were missing (less than 2% per measure) were imputed using the expectation-maximisation algorithm, and multivariate outliers were detected using Mahalanobis distance. Three hundred forty-five cases were ultimately analysed.

3.1. Population and Sampling

The sample consisted of the following representatives: Supply chain managers, procurement experts and logistics officers operating in the large business centres in Saudi Arabia, which are the most internationalised industrial centres in the Kingdom. Appropriate data have been gathered on the basis of supply-chain professionals, procurement specialists, technology officers, and compliance executives holding the positions that evoke DLT analyses, implementation budgets, ethical sourcing compliance and addressing consumer traceability or provenance questions. External validity is also compromised by purposive sampling because respondents are not picked at random, and may not be representative of the whole population of professionals, thus raising the chances of systematic bias towards divergence of opinion (Andrade, 2021). Non-response also adversely affects the parameter estimates through homogeneity bias. The study sample was selected based on participants’ levels of knowledge and understanding of DLT and ethical sourcing. This approach allowed target individuals to provide high-quality, truthful information, though the data may still be subject to common-method bias due to reliance on self-reports. A sample of 372 was selected using G*Power software, as 0.80 statistical power, 0.15 effect size, and 0.05 alpha level are required for SEM to detect medium effects. A total of 550 were distributed and 412 surveys were returned, of which 355 were deemed usable after data-quality screening, yielding an effective response rate of 64.54%.

3.2. Operationalisation of Variables

Consumer Trust (CT) is operationalised through five Likert-type items that gauge perceived ethical provenance and brand honesty, adapted from (Sepe, 2024). Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) adaption is characterised by five traceability- and fit-oriented statements, refined by (Liu et al., 2024; and Jin et al., 2024). Based on review and pilot testing, the original eight-item ESP survey by (Mancini et al., 2021; and Zu Ermgassen et al., 2022) was narrowed down to five items that were found to be either commodity-specific or having weaker item-total correlations. The items that have been retained have been chosen to prevent redundancy and maintain a balanced coverage of the four main dimensions of ethical sourcing: public disclosure, supplier auditing, environmental stewardship, and labour standards. The refinement keeps the content validity of the scale and increases its content understand and applicability to multi-industry supply chains in Saudi Arabia. All the items are shaped in the format of the five-point agreement scale.

3.3. Data Collection Instrument

The survey tool has been designed by adapting existing item scales to achieve contextual fit in the Saudi Arabia supply chain industry (the complete text of the items is presented in Appendix A). The scale for measuring of Distributed Ledger Technology adoption is adopted from (Liu et al., 2024; and Sepe, 2024). The wording was changed (e.g., to ‘deployment within existing IT infrastructure’) to use the local terminology and usage. Ethical Sourcing Practices was based on eight items suggested by (Mancini et al., 2021), resulting in a five-item instrument covering public disclosure, supplier auditing, environmental stewardship, and compliance with labour standards. The scale on perceived Consumer Trust comprised five items, adapted and harmonised for cultural resonance, covering provenance, credibility, and brand honesty. Everything used a five-point Likert response scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree).

In order to have a clear and appropriate questionnaire, a pilot study was carried out on 30 subjects who represented a general population of the study. These responses made us to rephrase the items and question format to enable individuals to respond and navigate the questionnaire. The content validity was thoroughly considered by academic specialists in supply chain management and information systems. Moreover, common method bias was a concern because of the use of self-reported data based on one survey tool. Procedural remedies like anonymity of respondents and reverse-coded items were used to evaluate and correct this bias. Further, the Single-Factor Test of Harman as suggested by (Podsakoff et al., 2003) was performed as part of the exploratory factor analysis that no single factor explained most of the data variance, therefore, explaining that CMB was of no major problem in this research. These measures contributed to enhancing the validity of the findings by reducing systematic biases of self-reported measurements.

3.4. Data Analysis Method

In this study, the data was assessed via SmartPLS 4.0 in order to conduct Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). The strategy consisted of two important actions to be taken. Firstly, there were validity and reliability tests on the measurement model to ascertain that the data were suitable in the structural model. One more look was taken to explore the impact that proper sourcing has on businesses’ decisions to use DLT and on their efforts to gain perceived consumer trust. Understanding how the results obtained in this manner affected the primary relationship was necessary, and variances were used to measure the value of each variable. The measurement model test included indicator reliability (outer loadings above 0.70), internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability above 0.70), convergent validity (AVE above 0.50), and discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker and HTMT below 0.85).

4. Results

The results show reliability and validity of the model then the interactions between the professionals are described. The results suggest that the relationship marketing efforts developed between the company and consumers are improved by the use of social responsibility and modern technology.

Table 1 is the example of 355 Saudi supply chain professionals. It is 64.8% male (n = 230), which means that there is a dominance in this gender in the logistics sector in the Kingdom and 35.2% (n = 125), which means that there is an imbalance. The age distribution is unbalanced with most of the respondents being between the age group of 21-30 years which has the highest percentage of 33.8 (n = 120) and the next highest figure of 29.6 (n = 105) in the age group of 31-40 years. The percentage of older practitioners is low: 22.5 percent between 41 and 50 years (n = 80) and 14.1 percent 50 and above. Overall, the survey can be described as a labour force whose potential talent is high in the future, and the experience in managing the organisation is high, which offers information about how Distributed Ledger Technology and ethical sourcing are implemented in Saudi supply chains.

Table 1. Demographic profile.

| Demographic Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 230 | 64.8 |

| Female | 125 | 35.2 | |

| Age | 21 – 30 | 120 | 33.8 |

| 31 – 40 | 105 | 29.6 | |

| 41 – 50 | 80 | 22.5 | |

| 51 + | 50 | 14.1 | |

| Total Participants | 355 | 100.0 |

Table 2 gives the results of reliability and validity of the constructs of perceived Consumer Trust, Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), and Ethical Sourcing Practices (ESP). The constructs possess the right internal consistency with the Cronbach alphas of more than 0.90 that is significantly higher than the traditional level of 0.70. The composite reliability scores (rhoa and rho c) are also good (0.911-0.949) and this represents excellent construct reliability. In addition to that, the mean variance extracted (AVE) of all the constructs is greater than 0.70, which is an adequate indication of good convergent validity. In particular, perceived consumer trust has the highest composite reliability (0.944) and the highest significant average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.773, indicating that its indicators are consistent and representative of the latent construct. Likewise, DLT and ESP show good reliability and validity, with AVEs of 0.734 and 0.789, respectively. In general, the table confirms that all the measurement constructs adopted in the model are reliable and valid, thereby providing confidence in the study’s structural relationships.

Table 2. Reliability and validity.

| Indicator | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Discriminant Validity | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

| Perceived Consumer Trust | CT1 | 0.850 | 0.926 | 0.928 | 0.944 | 0.715 | 0.773 |

| CT2 | 0.892 | ||||||

| CT3 | 0.908 | ||||||

| CT4 | 0.893 | ||||||

| CT5 | 0.850 | ||||||

| Distributed Ledger Technology | DLTA1 | 0.888 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.932 | 0.78 | 0.734 |

| DLTA2 | 0.856 | ||||||

| DLTA3 | 0.890 | ||||||

| DLTA4 | 0.823 | ||||||

| DLTA5 | 0.826 | ||||||

| Ethical Sourcing Practices | ESP1 | 0.855 | 0.933 | 0.935 | 0.949 | 0.695 | 0.789 |

| ESP2 | 0.899 | ||||||

| ESP3 | 0.915 | ||||||

| ESP4 | 0.897 | ||||||

| ESP5 | 0.875 |

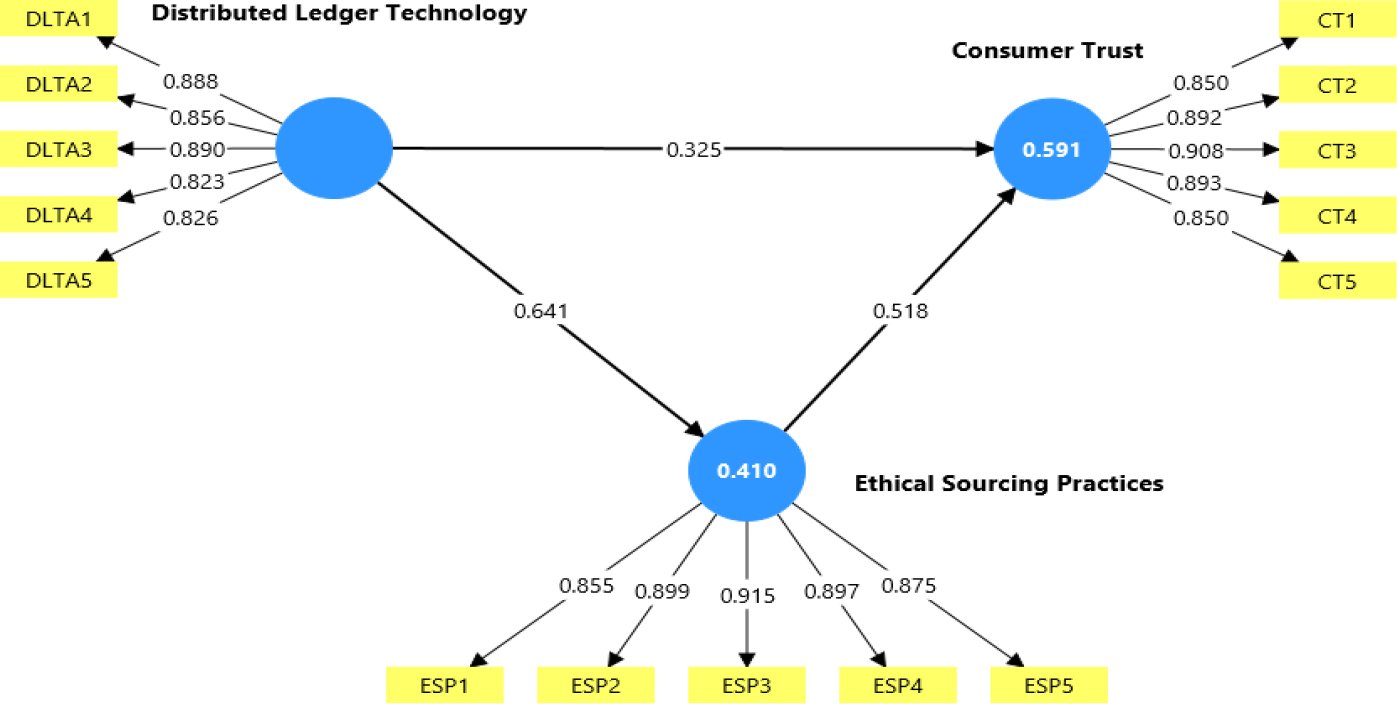

The path coefficients and the loading of indicators to present the strength of relationships between the three variables are presented in the structural model in Fig. (2); Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), Ethical Sourcing Practices (ESP), and perceived Consumer Trust (CT). The loadings of the indicators stand above 0.80, which means that there is a high reliability and construct validity. The total effect of DLT on ESP is substantial, which means that the significant favourable influence of ethical sourcing is obtained due to the implementation of ethical sourcing.

Fig. (2). Model coefficients.

Table 3 presents the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) values, assessing discriminant validity between constructs. The HTMT values range from 0.695 to 0.780, all of which are below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.85, indicating adequate discriminant validity. Specifically, the HTMT between Distributed Ledger Technology and perceived Consumer Trust is 0.715, between Ethical Sourcing Practices and perceived Consumer Trust is 0.780, and between Ethical Sourcing Practices and Distributed Ledger Technology is 0.695. These results suggest that the professionals are distinct yet related, thereby supporting the validity of the measurement model.

Table 3. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT).

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | |

| Distributed Ledger Technology <-> Perceived Consumer Trust | 0.715 |

| Ethical Sourcing Practices <-> Perceived Consumer Trust | 0.780 |

| Ethical Sourcing Practices <-> Distributed Ledger Technology | 0.695 |

Table 4 shows the Fornell-Larcker criterion for assessing discriminant validity. The diagonal values represent the square roots of the average variance extracted for each construct. In support, (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) argue that convergent validity is sufficient if these values exceed 0.60. The values in the diagonals are above this threshold, thus showing that the constructs have good convergent validity. The off-diagonal values represent the correlations between the constructs and that they are lower than their respective diagonal values support the construct validity of the model. This implication is that perceived Consumer Trust, Distributed Ledger Technology, and Ethical Sourcing Practices are not similar constructs but rather each construct describes a sufficient amount of the variance in the indicators of the construct and is also sufficiently differentiated to the other constructs.

Table 4. Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| Perceived Consumer Trust | Distributed Ledger Technology | Ethical Sourcing Practices | |

| Perceived Consumer Trust | 0.879 | ||

| Distributed Ledger Technology | 0.657 | 0.857 | |

| Ethical Sourcing Practices | 0.727 | 0.641 | 0.889 |

Table 5 summarises the direct PLS-SEM path coefficients. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) has a significant positive effect on Ethical Sourcing Practices (ESP) (β = 0.641, t = 13.58, p < 0.001) and a weaker yet considerable impact on perceived Consumer Trust (β = 0.325, t = 6.91, p < 0.001). Moreover, ESP strongly predicts perceived Consumer Trust (β = 0.518, t = 10.83, p < 0.001). These results confirm DLT’s crucial role in promoting ethical sourcing and enhancing perceived consumer trust. All effects are highly significant, supporting the validity of the theoretical model.

Table 5. Direct effect results.

| Coefficients | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | P Values | |

| Distributed Ledger Technology -> Consumer Trust | 0.325*** | 0.047 | 6.909 | 0.000 |

| Distributed Ledger Technology -> Ethical Sourcing Practices | 0.641*** | 0.047 | 13.578 | 0.000 |

| Ethical Sourcing Practices -> Consumer Trust | 0.518*** | 0.048 | 10.830 | 0.000 |

Note: ***significant at 1%

Table 6 shows that the indirect effect of Distributed Ledger Technology on perceived Consumer Trust via Ethical Sourcing Practices is significant (β = .331, t = 8.324, p < 0.001). Since the indirect and direct route is important, there is a partial mediation effect of the relationship by Ethical Sourcing Practices, which means that there is direct and indirect improvement in trust by DLT via ethical sourcing practices.

Table 6. Indirect effect results.

| Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | P Value | |

| Distributed Ledger Technology -> Ethical Sourcing Practices -> Perceived Consumer Trust | 0.331*** | 0.040 | 8.324 | 0.000 |

Note: ***significant at 1%

According to Table 7, the model accounts 59.1 and 0.41% are moderate explanatory power of the variance in perceived Consumer Trust and Ethical Sourcing Practices, respectively. The adjusted R-squared values (0.588 and 0.409) confirm strong explanatory power, indicating that the predictors effectively account for variability in both dependent constructs.

Table 7. Model summary.

| R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | |

| Perceived Consumer Trust | 0.591 | 0.588 |

| Ethical Sourcing Practices | 0.410 | 0.409 |

5. Discussion

The findings contribute to an in-depth understanding of how DLT improves ESP and builds indirect perceived consumer trust along Saudi Arabian supply chains as both H1 and H2 are accepted. The findings indicate a clear, transparent cause-effect pathway: first, DLT enhances transparency as a result of the ability to provide real-time traceability of products, facilitating monitoring of suppliers and enforcement of ethical standards. Second, DLT visibility works effectively within organisational routine changes like rigorous supplier screening and auditing. This correlation is relative to the Technology-Organisation-Environment framework that underlines that technology (DLT) can be effective only when it is in contact with organisational capabilities in terms of improved supplier management and environmental forces, such as regulatory frameworks and ESG demands. Continuing on the work of previous researchers, the article by (Antal et al., 2021) investigated the role of blockchain in enhancing supply chain transparency in the textile industry; one step ahead, however, the article demonstrates that the utility of DLT is not confined to certain industries, including the textile service or the agricultural industry. Instead, it is proved that industries such as petrochemicals, retail, and manufacturing also benefit in Saudi Arabia with traceability enabled by DLT. The effect of this research was stronger compared with prior work, for instance, (Kannan, 2021) in agrifood chains, suggesting that the digitalisation drive of Saudi Arabia and the ESG pressures from sovereign wealth funds and international investors impact the magnitude of the DLT effect. On the other hand, reliance on cross-sectional data reduces the possibility of inferring causality due to the influence of unobserved heterogeneity, as changes in transparency and governance practices will take their time to show up (Veltri et al., 2023).

Partial mediation detected in this study refines signalling theory by evidencing that blockchain-based disclosures do not automatically lead to perceived consumer trust. The present study, instead, underlines how additional verification mechanisms, such as third-party certifications, are required to support the blockchain claims. This is contrary to the work by (Joo & Han, 2021) who argued that only transparency can build up trust in sustainable food supply chains. Here, the direct path was weaker from DLT to perceived consumer trust, which suggests that consumers in Saudi Arabia are more cautious where purely technological assurances are concerned, aligning with the critique by (Sepe, 2024) on the limits of blockchain claims without supporting evidence of their truthfulness. Thus, this study contributes to signalling theory by detailing the conditions under which digital signals would succeed or fail. These are, for instance, QR-code-based information on provenance, improving perceived consumer trust when they co-occur with demonstrable improvements in ethics of sourcing, but fail when data are incomplete, poorly governed, or seen as mere marketing tools. This aligns well with (Ko et al., 2023) contention that trust by consumers in blockchain is conditional upon the underlying practices’ legitimacy and the credibility of institutions in control of the ledger. The findings herein also stress the limitation of literature that has come before, which normally assumes a direct link between blockchain and perceived consumer trust, without considering the context of wider governance.

The model describes a significant proportion of variance in the two endogenous constructs, with the lower R2 of ESP (0.410) than CT (0.591) denotes that the ethical sourcing practices are influenced by other organisational and institutional forces that are not reflected in the DLT and trust. The internal governance structure, long-standing supplier relationships, industry-specific laws, and access to ESG skills and auditing tools are all likely to shape the extent to which companies can act on analogous DLT potential into tangible sourcing modifications. In contrast, perceived consumer trust seems more immediately receptive to the compounded signal of transparency made possible by DLT and seen ethical sourcing pledges, which can be attributed to the explanation of the greater R2 of CT. All these contextual factors enhance the translation of technological investments into relational value. Theoretically, the results extend the Technology Organisation Environment (TOE) framework by introducing ESP as a mediating capability that turns technological artefacts into benefits for stakeholders, thereby bridging the adoption and outcome streams of research. They also elaborate on the signalling theory by observing that the reputational payoff of blockchain is not automatic but conditional more or less, the technology can be a directed credence amplifier in the event that it is introduced as a form of strict ethical audit (Chittipaka et al., 2023). The insights can be used by policymakers to develop incentive mechanisms where digital compliance grants are given to measurable social performance metrics to realize the Vision 2030, which seeks to turn the Kingdom into a transparent and sustainable logistics centre.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the empirical research demonstrates that Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) promotes a more stringent ethical sourcing and a major indicator of perceived consumer trust in supply chains of Saudi companies. DLT lowers information asymmetries by offering tamper-resistant audit trails, but on its own will not bring reputational benefits. The findings show that trust is improved when companies rely on DLT to create consistent reporting of fair labour practices, environmentally responsible practices and supplier’s adherence. The integrated TOE-signalling framework accordingly assists in explaining the role of the technological transparency and the perceived ethical performance to formulate the stakeholder perception in an emerging economy setting.

Recommendations

The alignment of corrective action plans and internal reporting procedures should be conducted in such a way that the claims reported by using QR codes are checked in a systematic manner; the managers must reconcile blockchain records with a supplier audit and non-compliance logs so that the digital indicators would be reflective of the practice. Companies must also invest in simple digital infrastructure and specific training of the upstream partners in order to decrease the provenance gap and enhance data quality all along the chain. To regulators and associations in the industry, a viable action will be to jointly develop standardised templates of digital certificates that define the minimum data fields on origin, labour standards, and environmental indicators, frequent QR or API shapes, and proper verification processes. The availability of these templates must be via common, low-cost platforms offered with technical helpdesks, low-cost onboarding of small and medium-sized enterprises, and incremental compliance schedules that appreciate the limited financial and staffing resources of SMEs. These tangible, circumstantial actions can reduce the costs of integration of the SMEs and make the use of the DLT-based sourcing of ethical conduct more viable throughout the Saudi supply base.

Ethical Considerations

The institutional review board in question gave a formal consent before any data were collected. The survey was at all times voluntary and all the subjects gave their consent to partake in the survey in advance electronically. All the analysis was done in confidence and no data that might identify the participants was gathered, the researcher was the only person who could access the data. Scholars made sure that there was no penalty on them who could leave anytime.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

T.E. has contributed to conceptualization, idea generation, problem statement, methodology, results analysis, results interpretation.

Human and Animal Rights

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and material

The data will be made available on reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author [T.E.].

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Declared none.

Appendix A

Questionnaire

Demographic Profile

Gender

- Male

- Female

Age

- 21 – 30

- 31 – 40

- 41 – 50

- 51 +

Scale: Strongly Disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Neutral = 3, Agree = 4, Strongly Agree = 5

Consumer Trust

- Our customers believe our products are sourced ethically.

- Our customers recognise our brand as trustworthy.

- Customers perceive us as honest in our sourcing claims.

- Our transparency about sourcing increases customer trust.

- Customers value our openness about where and how products are made.

Adapted from (Sepe, 2024)

Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) Adoption

- DLT improves the traceability of our supply chain operations.

- DLT enhances the transparency of sourcing activities.

- DLT ensures the integrity of transactional records.

- DLT fits well with our organisational goals.

- DLT is suitable for our supply chain management needs.

Adapted from (Sepe, 2024; Liu et al., 2024)

Ethical Sourcing Practices

- Our company publicly shares information about our sourcing practices.

- We regularly audit our suppliers for adherence to ethical practices.

- We consider environmental impact in our sourcing decisions.

- We prioritise suppliers who adhere to ethical labour practices.

- Ethical sourcing is an integral part of our procurement strategy.

Adapted from (Mancini et al., 2021)

REFERENCES

Al-Hadwer, A., Tavana, M., Gillis, D., & Rezania, D. (2021). A systematic review of organizational factors impacting cloud-based technology adoption using the technology-organization-environment framework. Internet of Things, 15, 100407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2021.100407.

Al-Kubaisy, Z. M., & Al-Somali, S. A. (2023). Factors influencing the adoption of blockchain technologies in supply chain management and logistics sectors: Cultural compatibility of blockchain solutions as a moderator. Systems, 11(12), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11120574.

Almabrok, H. A. (2023). Blockchain for supply chain management: To enhance transparency, traceability, and efficiency. African Journal of Advanced Pure and Applied Sciences (AJAPAS), 239-253. https://aaasjournals.com/index.php/ajapas/article/view/618.

Andrade, C. (2021). The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 43(1), 86-88. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0253717620977000.

Antal, C., Cioara, T., Anghel, I., Antal, M., & Salomie, I. (2021). Distributed ledger technology review and decentralized applications development guidelines. Future Internet, 13(3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13030062.

Asante, M., Epiphaniou, G., Maple, C., Al-Khateeb, H., Bottarelli, M., & Ghafoor, K. Z. (2021). Distributed ledger technologies in supply chain security management: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 70(2), 713-739. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2021.3053655.

Bernards, N., Campbell-Verduyn, M., & Rodima-Taylor, D. (2024). The veil of transparency: Blockchain and sustainability governance in global supply chains. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 42(5), 742-760. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544221142763.

Biswas, D., Jalali, H., Ansaripoor, A. H., & De Giovanni, P. (2023). Traceability vs. sustainability in supply chains: The implications of blockchain. European Journal of Operational Research, 305(1), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2022.05.034.

Chittipaka, V., Kumar, S., Sivarajah, U., Bowden, J. L. H., & Baral, M. M. (2023). Blockchain Technology for Supply Chains Operating in Emerging Markets: An Empirical Examination of the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework. Annals of Operations Research, 327(1), 465-492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04801-5.

Da Silva, C. F., & Moro, S. (2021). Blockchain technology as an enabler of consumer trust: A text mining literature analysis. Telematics and Informatics, 60, 101593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101593.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002224378101800104.

Gorbunova, M., Masek, P., Komarov, M., & Ometov, A. (2022). Distributed ledger technology: State-of-the-art and current challenges. Computer Science and Information Systems, 19(1), 65-85. https://doi.org/10.2298/CSIS210215037G.

Government of Saudi Arabia. (2025). National Industrial Development and Logistics Program. Vision2030.Gov.sa. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs/national-industrial-development-and-logistics-program.

Heldt, L., & Pikuleva, E. (2025). When upstream suppliers drive traceability: A process study on blockchain adoption for sustainability. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 55(3), 196-222. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2024-0022.

Jin, M., Li, Q., Sethi, S., Xiong, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2024). From Translucency to Transparency: Strategic Blockchain Adoption for Quality Disclosures in Supply Chains with Competing Manufacturers. Available at SSRN 5021657. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5021657.

Joo, J., & Han, Y. (2021). Evidence of distributed trust in a blockchain-based sustainable food supply chain. Sustainability, 13(19), 10980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910980.

Kannan, D. (2021). Sustainable procurement drivers for extended multi-tier context: A multi-theoretical perspective in the Danish supply chain. Transportation research part E: Logistics and transportation review, 146, 102092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.102092.

Ko, T., Lee, J., Park, D., & Ryu, D. (2023). Supply chain transparency as a signal of ethical production. Managerial and Decision Economics, 44(3), 1565-1573. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3765.

Kraft, T., Valdés, L., & Zheng, Y. (2022). Consumer trust in social responsibility communications: The role of supply chain visibility. Production and Operations Management, 31(11), 4113-4130. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13808.

Kshetri, N. (2021). Blockchain and sustainable supply chain management in developing countries. International journal of information management, 60, 102376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102376.

Laraichi, S. O. F. I. A. (2020). The impact of packaging transparency and product texture on perceived healthiness and product trust. In Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy (Vol. 49, p. 64604). https://proceedings.emac-online.org/pdfs/A2020-64604.pdf.

Liu, H., Osman, L. H., Omar, A. R. C., & Rosli, N. (2024). Blockchain adoption factors in agricultural supply chains: A PLS-SEM study. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(11), Article 8411. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v8i11.8411.

Mancini, L., Eslava, N. A., Traverso, M., & Mathieux, F. (2021). Assessing impacts of responsible sourcing initiatives for cobalt: Insights from a case study. Resources Policy, 71, 102015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102015.

McGrath, P., McCarthy, L., Marshall, D., & Rehme, J. (2021). Tools and Technologies for Transparency in Sustainable Global Supply Chains. California Management Review, 64(1), 67-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256211045993.

Mohamed, S. K., Haddad, S., Barakat, M., & Rosi, B. (2023). Blockchain technology adoption for improved environmental supply chain performance: The mediation effect of supply chain resilience, customer integration, and green customer information sharing. Sustainability, 15(10), 7909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107909.

Mohammed, I., Nangpiire, C., Detoh, W. M., & Fataw, Y. (2024). The effect of blockchain technology in enhancing ethical sourcing and supply chain transparency: Evidence from the cocoa and agricultural sectors in Ghana. African Journal of Empirical Research, 5(2), 55-64. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajempr/article/view/278245.

Mubarik, M., Raja Mohd Rasi, R. Z., Mubarak, M. F., & Ashraf, R. (2021). Impact of blockchain technology on green supply chain practices: evidence from an emerging economy. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 32(5), 1023-1039. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-11-2020-0277.

N’Dri, A. B., & Su, Z. (2024). Successful configurations of technology–organization–environment factors in digital transformation: Evidence from exporting small and medium-sized enterprises in the manufacturing industry. Information & Management, 61(7), 104030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2024.104030.

Nguyen, L. D., Bröring, A., Pizzol, M., & Popovski, P. (2022). Analysis of distributed ledger technologies for industrial manufacturing. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 18055. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22612-3.

Nurgazina, J., Pakdeetrakulwong, U., Moser, T., & Reiner, G. (2021). Distributed ledger technology applications in food supply chains: A review of challenges and future research directions. Sustainability, 13(8), 4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084206.

Özkan, E., Azizi, N., & Haass, O. (2021). Leveraging smart contracts in project procurement through DLT to gain sustainable competitive advantages. Sustainability, 13(23), 13380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313380.

Park, A., & Li, H. (2021). The Effect of Blockchain Technology on Supply Chain Sustainability Performance. Sustainability, 13(4), 1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041726.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lee, J. Y. (2003). The mismeasure of man (agement) and its implications for leadership research. The leadership quarterly, 14(6), 615-656. https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2003-08045-010.

Rapezzi, M., Pizzi, G., & Marzocchi, G. L. (2024). What you see is what you get: the impact of blockchain technology transparency on consumers. Marketing Letters, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-024-09723-9.

Sepe, F. (2024). Blockchain Technology Adoption in Food Label Systems. The impact on consumer purchase intentions. SINERGIE, 42(1), 241-264. https://doi.org/10.7433/s123.2024.10.

Singh, V., & Sharma, S. K. (2023). Application of blockchain technology to shape the future of the food industry, driven by transparency and consumer trust. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 60(4), 1237-1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-022-05360-0.

Toukabri, M., & Chaouachi, M. (2025). Exploring the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility, Blockchain Transparency, and Cultural Alignment on Consumer Trust and Premium Pricing Willingness for Local Food in Saudi Arabia. Current Research in Nutrition & Food Science, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.13.1.20.

Varma, A., Dixit, N., Ray, S., & Kaur, J. (2024). Blockchain technology for sustainable supply chains: A comprehensive review and prospects. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(3), 980-994. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2024.21.3.0804.

Vazquez, M., E. I., Bergey, P., & Smith, B. (2024). Blockchain technology for supply chain provenance: increasing supply chain efficiency and consumer trust. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 29(4), 706-730. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-08-2023-0383.

Veltri, G. A., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Folkvord, F., Theben, A., & Gaskell, G. (2023). The Impact of Online Platform Transparency on Consumers’ Choices. Behavioural Public Policy, 7(1), 55-82. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.11.

Vinayavekhin, S., Banerjee, A., & Li, F. (2024). “Putting your money where your mouth is”: An empirical study on buyers’ preferences and willingness to pay for blockchain-enabled sustainable supply chain transparency. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 30(2), 100900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2024.100900.

Wei, G. (2023). The impact of blockchain technology on integrated green supply chain management in China: A conceptual study. Journal of Digitainability, Realism & Mastery (DREAM), 2(02), 58-65. https://doi.org/10.56982/dream.v2i02.112.

Zhou, Y., Manea, A. N., Hua, W., Wu, J., Zhou, W., Yu, J., & Rahman, S. (2022). Application of distributed ledger technology in distribution networks. Proceedings of the IEEE, 110(12), 1963-1975. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2022.3181528.

Zu Ermgassen, E. K., Bastos Lima, M. G., Bellfield, H., Dontenville, A., Gardner, T., Godar, J., … & Meyfroidt, P. (2022). Addressing Indirect Sourcing in Zero Deforestation Commodity Supply Chains. Science Advances, 8(17), eabn3132. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn3132.

Licensed

© 2025 Copyright by the Authors.

Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.

Article Contents Author Yazeed Alsuhaibany1, * 1College of Business-Al Khobar, Al Yamamah University, Saudi Arabia Article History: Received: 03 September,

Article Contents Author Muhammad Arslan Sarwar1, * Maria Malik2 1Department of Management Sciences, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan; 2COMSATS

Article Contents Author Tarig Eltayeb1, * 1College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Kuon Keong Lock1, * and Razali Yaakob1 1Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia,

Article Contents Author Shabir Ahmad1, * 1College of Business, Al Yamamah University, Al Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Article History:

Article Contents Author Ghanima Amin1, Simran1, * 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Sialkot, Sialkot 51310, Pakistan Article History: Received:

PDF

PDF